Teaching methods for learning outcomes

Tom Bourner

My aim for this paper is to offer an approach to choosing teaching methods in higher education (HE). I hope it will be particularly useful at three levels: (1) where academic staff are designing courses; (2) where individual lecturers are planning how they will deliver a particular course unit; and (3) where lecturers are deciding what to do in a particular teaching session. I have written lecturer in inverted commas as the term lecturer rather prejudges the issue of what teaching method to employ. That is precisely the issue I want to explore. The rst part of the paper offers the approach in principle. The remaining parts go on to operationalize it. That is crucial to my purpose in writing the paper, which is to inuence the practice of teaching and thereby learning in higher education. It is enlightened practice, nowadays, to use the term teaching and learning methods rather than teaching methods. This reminds us that the purpose of teaching is learning and discourages the separation of teaching and learning. In this paper, however, there is no danger of my losing sight of the learning side of teaching, so I will focus on teaching methods per se.

The author Tom Bourner is Principal Lecturer in the Centre for Management Development, University of Brighton, UK. Abstract Focuses on learning outcomes in debates on teaching methods in higher education (HE). Presents six core learning outcomes and ten common teaching methods for each of the learning outcomes. Concludes that the search for any universally best teaching method is bound to be fruitless and should give way to the search for better ways of achieving particular learning outcomes. Recommends the widening of the repertoire of teaching methods available to academic staff as a means of diminishing the severity of the trade-off between teaching effectiveness and teaching efciency as the unit of teaching resource continues to fall.

Part 1: Choosing teaching methods

There was probably a time when academic staff in HE simply followed the teaching methods that they had experienced as students. Nowadays there is increasing discussion about teaching methods. There are many reasons for this, including the following. First, a declining unit of teaching resource has put the spotlight on teaching methods as teaching staff costs are a high proportion of total costs. Second, developments in technologies for communicating and disseminating information have a large potential impact on the practice of teaching as an activity in which communicating and disseminating information are very signicant aspects. Third, increased focus on, and publicity of, performance indicators of teaching quality have also increased the attention paid to teaching methods. None of these reasons are likely to go away so it is unlikely that concern about teaching methods in universities will subside. On the contrary each of the reasons is likely to 344

Education + Training Volume 39 Number 9 1997 pp. 344348 MCB University Press ISSN 0040-0912

�Teaching methods for learning outcomes

Education + Training Volume 39 Number 9 1997 344348

Tom Bourner

become more compelling and so too will the issue of teaching methods. What has struck me about most of the discussion that I have heard about teaching methods is the absence of reference to aims. This is in contrast to my experience of university discussion in most other contexts, where aims are used as the criteria for evaluating methods. For example, when I have sat on research degrees committees, consideration of research degree proposals has usually started with questions such as Are the aims appropriate for the award that is being sought? and Are the proposed methods appropriate to achieve the aims that have been selected? I believe that this is sound practice. By the same token it would be sound practice to bring the learning outcomes that we seek for our students into discussions of proposed teaching methods. No discussion of teaching methods makes much sense without prior consideration of what we are trying to achieve with the teaching methods. Teaching methods are not an end in themselves, they are a means to an end. They are the vehicle(s) we use to lead our students towards particular learning outcomes. The principle that I want to establish as practice is that we evaluate our teaching methods against the learning outcomes that we are seeking for our students. I suspect that there is unlikely to be much dissent from this principle in theory. However, the principle has limited value unless it can be operationalized. The rst stage in operationalizing it is to clarify the learning outcomes at which we are aiming. The second stage involves developing a contingency approach to the choice of teaching methods whereby tness for purpose replaces nave judgements of better and worse. Part 2 of this paper presents a range of HE learning outcomes.

Disseminate up-to-date knowledge. Develop the capability to use ideas and information. Develop the students ability to test ideas and evidence. Develop the students ability to generate ideas and evidence. Facilitate the personal development of students. Develop the capacity of students to plan and manage own learning. My rationale for each of these aims is: (1) Disseminate up-to-date knowledge. I suspect that for most people who have not received a higher education the main purpose of HE is to deliver information and ideas at a level beyond that which is possible at school. One of the things that distinguishes a university is scholarship and it is reasonable to expect that within a university the information and ideas that are conveyed should be up-to-date (i.e. the product of ongoing scholarship). (2) Develop the capability to use ideas and information. Understanding can occur at different levels: intellectual assent to a concept or idea does not necessarily encompass the ability to use it in a range of applications. It is sometimes said that the ability to apply a concept goes beyond mere intellectual assent to it. Certainly the ability to use a concept skilfully goes beyond intellectual assent. The capacity to use ideas and information involves moving beyond comprehension of a principle in the abstract, to an appreciation of its range of applicability: where, when and how it is appropriate to use it. (3) Develop critical faculties. The rationale for the development of critical faculties as a major part of the teaching mission of higher education has been forcefully argued by Sir Douglas Hague (Hague was Chair of the Economic and Social Research Council during most of the 1980s. He is now at Templeton College, Oxford) (Hague, 1991):

Academics must believe that acquiring the ability to test ideas and evidence is the primary benet of university learning.

Part 2: Learning outcomes and teaching methods

As someone who has participated in many discussions about teaching and learning methods over almost 30 years of teaching in higher education I have reached a clear view of the learning aims of higher education (see Bourner, 1996a, for a fuller account). They are:

The ability to test ideas and evidence is a signicant transferable skill. Teaching students to use their critical faculties means that they will be less likely to be taken in by the assumptions, assertions 345

�Teaching methods for learning outcomes

Education + Training Volume 39 Number 9 1997 344348

Tom Bourner

and unsupported statements of those who would seek to control their lives. It is signicant that this aim is a skill, that this aim uses the word develop rather than disseminate and that it introduces a clear relationship between teaching and research which was absent from the rst two aims above. (4) Develop the students ability to generate ideas and evidence. This aim complements the above aim of developing the students ability to test ideas and evidence. Developing critical faculties is one side of the equation and developing creative faculties is the other side of the equation. Answering questions is valuable but so too is nding the right questions to ask. There is a parallel between the aims of research and teaching here: each is concerned with both theory generation and theory testing (learning is concerned with generating and testing personal theories and research is concerned with generating and testing theories in a way that contributes to shared knowledge). (5) Facilitate the personal development of students. Personal development impacts in a major way on the effectiveness of people in their professional roles. I sometimes ask managers to think back to the most effective manager that they have ever had and the least effective one and then to identify the differences. They very rarely offer differences in terms of knowledge of marketing, statistics or corporate strategy, etc. Instead, they usually offer qualities for which the prerequisite is selfknowledge and the ability to act on that self-knowledge (exible, calm in a crisis, visionary, developer, inspirational, etc.) (see Bourner, 1996b, for an uncomplicated account of how selfknowledge contributes to effective management, dened in terms of contribution to the commercial success of organizations). (6) Develop the capacity of students to plan and manage own learning. The rationale for this aim is well-expressed by the following statement in a book entitled Action Learning in Higher Education:

our ultimate goal in higher education must be to encourage students to be responsible for, and in control of, their own learning, and to make the conceptual change from learning a science (i.e. a

subject or discipline) to becoming a problem-solver, independent of their teachers attitudes, beliefs and methodologies (Zuber-Skerritt, 1992, p. 24).

The idea embodied in that resonates well with the old saying that if you give someone a sh you feed them for a day and if you teach someone to sh you feed them for a lifetime. The aim of developing the capacity of students to plan and manage their own learning has to date found its loudest expression in courses of higher education based on learning contracts and it is interesting to witness the growing importance of continuing professional development within the graduate professions and the growing commitments of governments to the idea of lifelong learning. A hierarchy of learning aims? I am reluctant to see the six learning aims identied above in terms of a hierarchy. I believe that they are each important and that it is the challenge for us as educators in higher education to achieve as many of those aims as we can. The only hierarchy is in terms of more or less. An inferior educational experience will embrace few of these aims: a superior educational experience will embrace more of them. Quality of education is dened in terms of all of those aims. My fear with the cutting of the unit of resource in higher education is that we become less ambitious in terms of the range of learning aims that we seek to achieve and that the educational experience of our students will consequently become impoverished[1]. A measure of our success will be the extent to which we are able to retain the range of learning outcomes that we can achieve with our students.

Part 3: Teaching methods a contingency approach

The argument so far is that: to discuss meaningfully teaching methods it is necessary to be clear about learning aims; the range of learning aims of higher education is broad; and one way of impoverishing the learning experience of students is to lower our aspirations in terms of learning aims. This section argues against the search for universally better or worse teaching methods (though any particular teaching/learning method can be done more or less well) and

346

�Teaching methods for learning outcomes

Education + Training Volume 39 Number 9 1997 344348

Tom Bourner

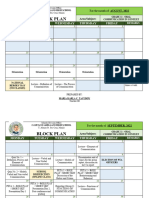

in favour of the search for more and less appropriate teaching methods for particular learning aims. Each of the above list of potential learning outcomes suggests a large range of teaching methods to reach the outcome. Restricting myself to only ten of the more common teaching methods for each gives Table I (these were the methods offered by participants at a workshop session at a Teaching and Learning Methods Conference at the University of Brighton in July 1996). It is clear from Table I that different teaching methods are appropriate to different learning aims. There is a little overlap, to be sure, where one method serves the purposes of more than one aim but possibly much less overlap than might be anticipated. An important message of Table I is that when there are disagreements about different teaching and learning methods the source of the disagreements is likely to be found in

Table I Teaching and learning methods for different learning aims

differences in the learning aims that are being assumed.

Summary and conclusions

In recent years teaching methods have moved much higher up the agenda within institutions of higher education. They are likely to move higher still as the unit of teaching resource continues to fall, the cost of communicating and disseminating information via new technologies continues to fall and emphasis on teaching quality continues to rise. No discussion of teaching methods makes much sense without reference to the learning outcomes that they are meant to achieve. Much disagreement about teaching methods can be traced back to disagreement about learning aims and outcomes. Indeed much can be reasonably inferred about a persons implicit beliefs about the purpose and aims of

Disseminate up-to-date knowledge Ten common teaching methods

Develop the capability to use ideas and information

Learning aims Develop the Develop the students ability students ability to generate to test ideas ideas and and evidence evidence

Facilitate the personal development of students

Develop the capacity of students to plan and manage own learning

1. Lectures 1. Case studies 1. Seminar and 1. Research 1. Feedback 1. Learning 2. Up-to-date 2. Practicals tutorials Projects 2. Action learncontracts textbooks 3. Work experi2. Supervision 2. Workshops ing 2. Projects 3. Reading lists ence 3. Presentations on techniques 3. Learning 3. Action Learn4. Hand-outs 4. Projects 4. Essays of creative contracts ing 5. Guest 5. Demons5. Feedback on problem 4. Role play 4. Workshops lectures trations written work solving 5. Experiential 5. Mentors 6. Use of exercis- 6. Group work6. Literature 3. Group worklearning 6. Reective logs es that require ing reviewing ing 6. Learning logs and diaries students to 7. Simulations 7. Exam papers 4. Action learn7. Structured 7. Independent nd up-to(e.g. computer 8. Critical assessing experiences in study date knowlbased) ment 5. Lateral thinkgroups 8. Dissertations edge 8. Problem9. Peer assessing 8. Reective 9. Work place7. Develop skills solving ment 6. Brainstorming documents ment in using library 9. Discussion and 10. Self-assess7. Mind-mapping 9. Self-assess10. Portfolio and other debate ment 8. Creative ment development learning 10. Essay-writing visualization 10. Proling resources 9. Use of relax8. Directed ation techprivate study niques 9. Open learning 10. Problem materials solving 10. Use of the Internet 347

�Teaching methods for learning outcomes

Education + Training Volume 39 Number 9 1997 344348

Tom Bourner

higher education by their views on teaching methods. I believe that the core learning aims of higher education are to: (1) Disseminate up-to-date knowledge. (2) Develop the capability to use ideas and information. (3) Develop critical faculties. (4) Develop the students ability to generate ideas and evidence. (5) Facilitate the personal development of students. (6) Develop the capacity of students to plan and manage own learning. There is no hierarchy among these aims and they are not alternatives. The search for universally better or worse teaching methods misses the point. It is bound to be fruitless, and should give way to the search for better and worse ways of achieving a particular learning outcome. In this paper I have identied a range of important learning outcomes and a selection of teaching methods. I have not suggested that the range of learning aims is the only relevant consideration in choosing teaching methods. Clearly, there are other factors that must be taken into account such as resource constraints and the skills of the teaching staff, including the breadth of their repertoire of teaching methods. If the teaching repertoire of academic staff is limited to only a few of the methods then that is the real choice available to us. Widening that repertoire will enable us to select

more effective methods of achieving a particular learning aim and enable us to select a lower cost method over a higher cost method. In other words, the greater the repertoire of teaching methods available to staff, the less severe the trade-off between teaching effectiveness and teaching efciency as the unit of teaching resource falls. The range of learning outcomes is not the only factor in choosing teaching methods but choosing teaching methods without reference to identied learning outcomes is like the play Hamlet without the Prince of Denmark.

Note

1 Let me illustrate this with the (reductio ad absurdum) suggestion that if the unit of resource continues to fall then eventually we could reach a position where we present new students with a set of textbooks (or a reading list!) on the day that they enrol together with the dates of the examinations and that would be the extent of our contribution to their educational experience. On that basis, it is clear that it is easy to manage a reducing unit of resource: by simply reducing the level of educational input.

References

Bourner, T. (1996a), The learning aims of higher education, Education + Training, Vol. 38 No. 3, pp. 10-16. Bourner, T. (1996b), Personal development to improve management performance, Management Development Review, Vol. 9 No. 6, pp. 4-9. Hague, D. (1991), Beyond Universities: A New Republic of the Intellect, Institute of Economic Affairs, London. Zuber-Skerrett, O. (1992), Action Learning in Higher Education, Kogan-Page, London.

348