Lancaster University | Week 1 Lecture: Part 3

So we've just looked at markup, and I think, for most purposes, you can really forget it exists. So all it is,

is the magic behind the scenes that allows you to do various forms of intelligent searches as a linguist,

or a person interested in language, looking at corpus data. But when I talked about something being

representative before, I sort of started to imply that corpora come, if you like, in different shapes and

sizes, or at least in different flavours. There are different things you can do with different types of

corpora.

By the way, 'corpora' is the plural of corpus. It's a very unfortunate plural, but that's the plural we're

stuck with. So different types of corpora, we have to say. How might we begin to sort of rough out a sort

of topology of different types of corpus? Well, for example, we could talk about genre.

What is the sort of principle genre? What is the range of genres represented in that corpus? So I might

have quite a specialised corpus where I had a very focused genre. Let's just say, for example,

newspaper material. Very focused. Very specialised. I could look at the language of newspapers, and

the time it was gathered, the place it was gathered, using that type of corpus.

And I mentioned time already, time also gives a sense of some type of specialisation and limitation of

the focus of the data. So, for example, if I'm interested in looking at news reported in the 21 first

century, looking at a newspaper from 1651 is clearly problematic in terms of time. But if I'm interested in

newspapers in the 1650s in England, something from 1651, a collection of newspapers that are very

specialised (British English -1651 -newspapers), that, for me, is very helpful. And also, as again, I've

just implied, the location or, if you like, the variety of language sometimes that it's produced in also

creates another force of specialisation.

So there's a whole range of ways in which the corpus might be more tightly focused, but very often, we

want to appeal to some type of general corpus, as I talked about before. And here, we can look at large

corporas, such as the British National Corpus, 100 million words of spoken and written English. Note, by

the way, that spoken and written, that mode of communication, can also generate different types of

corpora. Spoken language is somewhat different to written language in a range of ways, as you'll

discover.

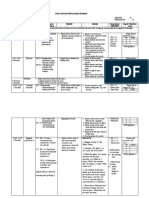

But the British National Corpus is composed of a large variety of genres of writing, nearly 88 million

1

�words of it. Informative writing, in broadly eight types, in world affairs, leisure, the arts, commerce and

finance, belief and thought, social science, applied science, natural and pure science, and also,

imaginative writing, though the one genre that is represented there is fiction. And you can see on the

slide, the relative proportions of data in those categories. So that's an attempt to produce a broad

collection of British English in a range of types of writing.

On the speech side, just over 10 million words of speech, and, of course, producing that was a major

undertaking. Lots of people carried around a tape recorder, recording everyday conversations, and

then some very brave and noble people typed that up so that we could search it by using a keyword

and searching for words, etcetera of the data. It's broadly split in two, the so-called spoken

demographic, which is informal conversation. Some pulled from across the UK and across a range of

social classes, a range of ages, and also, male and female.

And then spoken context governed, what you might call more task-centred speech recorded in specific

locations because we know that spoken language can vary by location. I might use a more formal way

of speaking if I'm talking to my bank manager then when I'm talking to my nephew, something like that.

So trying to think about, if you like, the shape of spoken language and represent that, as best we could

in that spoken collection there. Later on in the course, you'll actually be getting the opportunity to use

and search in the British National Corpus, and that should prove very interesting indeed.

So that's an example of a large corpus, which tries to represent the language in general. But there are

still further types of corpora. There are multilingual corpora. Well, to some extent, you could say, well,

there's corpus of English, there's a corpus of Spanish, I can contrast the two languages by looking at

that. I can collect those corpora also to ensure that the contrast is productive. You don't want to collect

the corpus of English looking at one genre and then looking at a completely different genre in Spanish.

Some of the things that you observe might be an artefact or a byproduct, if you like, of the genre in

question. So very often people try to balance those corpora. They're going to look across languages so

that they're broadly comparable in terms of the design decisions that have been made in creating them.

But in a sort of weaker sense of multilingual, perhaps you can look at varieties of one language.

So you can contrast American English, British English, Indian English, if you like. Large collections of

corpora have been produced exactly to do that. The so-called ICE family of corpora, the International

Corpus of English, initiative run out of University College London, where they've tried to build corpora

2

�with roughly the same design for a whole range of varieties of English to allow people to look at the

differences between those varieties of English.

There are also sometimes things called parallel corpora. Again, let's think about English and Spanish, a

corpus I built was called the CRATER corpus, and there we had English original texts and their

translations into Spanish. That rather distinctive, of course, from comparing native speaker English to

native speaker Spanish. You're looking at something which is being translated, so as well as being able

to look, if you like, through a distorted mirror at the language, you could also focus on those distortions,

if you'd like, and look at what the process of translation does when you translate from English into

Spanish. So if you also have that native speaker Spanish corpus for purposes of comparison, you could

do some very interesting work using this type of corpus data, looking at what the process of translation

does when you convert from English into Spanish and then compare it to native speaker Spanish.

There's also the learner corpus. And time, again, I think throughout this course in some of the

conversations that you'll hear in the conversation videos and also in one of the lectures, we'll be looking

at learner corpora. Language data produced by people who are speaking in a second language. So

let's say, for example, if you've heard me speak French, and it isn't pretty, so I hope you don't have to,

but if you hear me trying to speak French, you'll hear learner language. I was taught French at school.

I'm a native speaker of English, and my production in this so-called L2, second language, could be

gathered together into a corpus so that you could systematically analyse, for example, the many errors

I'm likely to make when I speak French, I'm afraid. Very interesting, as we'll see.

Also, of course, we have historical or diachronic corpora. Corpora that allow us to look at the language

developing or changing or sometimes, remaining the same, over a long period of time. A good example

of that is the Helsinki corpus, 1 and 1/2 million words of texts focused on English between 1700 and 700

AD. You can go back through time looking at changes in the English language using a corpus like that.

Very, very helpful.

Why very, very helpful? Well, put it this way, if you didn't agree with the corpus approach and you really

thought it was best just to work on the basis of intuitions, or maybe observing a few individuals and

taking notes, well, I wouldn't necessarily agree with you that that's always the best way of working, but I

would challenge you to use that way of working in looking at say early modern English. There are no

speakers of early modern English left. There's nobody you can observe who speaks early modern

3

�English. You have very few, if any, intuitions about early modern English. And what you then really do

need to do is look back at the record of it and study that.

Another type of corpus is the monitor corpus. Very, very useful for looking at very rapid change in

language. Typically, new words coming into use and old words dying out quite rapidly. A good example

of that is the 'Bank of English' developed at Birmingham University in the UK. And it's constantly, if you

like, being added to. Think about the formation of sedimentary rocks, this endless layering of mud being

compressed to form this rock within which are strata.

And I think the monitor corpus is very easily viewed in that way. As the language gets pressed down

into this corpus, you're able to go back through the different layers of it, back through time, but on a

very fine grained basis. This type of corpus is updated usually almost daily, at least very frequently. So

you can see some new words come into use. You can see their birth. Very, very helpful for linguists.

Now, there are many other types of corpora, but that gives you a good flavour of the types of corpus

data that you'll be hearing about on this course.