Moreno-Dominguez Et Al (2019)

Uploaded by

ameliaMoreno-Dominguez Et Al (2019)

Uploaded by

ameliaORIGINAL RESEARCH

published: 21 March 2019

doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00582

Body Mass Index and Nationality

(Argentine vs. Spanish) Moderate the

Relationship Between Internalization

of the Thin Ideal and Body

Dissatisfaction: A Conditional

Mediation Model

Edited by:

Silvia Moreno-Domínguez 1* , Guillermina Rutsztein 2 , Thomas A. Geist 3 ,

Antonios Dakanalis, Emily E. Pomichter 3 and Antonio Cepeda-Benito 3*

University of Milano-Bicocca, Italy 1

Departamento de Psicología, Universidad de Jaén, Jaén, Spain, 2 Facultad de Psicología, Universidad de Buenos Aires,

Reviewed by: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 3 Department of Psychological Science, The University of Vermont, Burlington, VT, United States

Siân McLean,

Victoria University, Australia

Netalie Shloim, It is believed that Women’s exposure to Western sociocultural pressures to attain a

University of Leeds, United Kingdom “thin-ideal” results in the internalization of a desire to be thin that consequently leads

*Correspondence: to body dissatisfaction (BD). It is also well documented that body mass index (BMI;

Silvia Moreno-Domínguez

smoreno@ujaen.es kg/m2 ) correlates with BD. We tested for the first time a conditional mediation model

Antonio Cepeda-Benito where thin-ideal Awareness predicted BD through Internalization of the thin ideal and

acepeda@uvm.edu

the path from Internalization to BD was hypothesized to be moderated by BMI and

Specialty section: Nationality (Argentine vs. Spanish). The model was tested with a sample of 499 young

This article was submitted to women (age = 18 to 29) from Argentina (n = 290) and Spain (n = 209). Awareness

Eating Behavior,

a section of the journal

and internalization were measured with the SATAQ-4 (Schaefer et al., 2015) and BD

Frontiers in Psychology was measured with the BSQ (Cooper et al., 1987). The model was analyzed using

Received: 09 December 2018 PROCESS v3.1 (Hayes, 2018). As hypothesized, thin-ideal awareness predicted BD

Accepted: 01 March 2019

through internalization and the path from internalization to BD was moderated by

Published: 21 March 2019

BMI and nationality. Specifically, internalization predicted BD at all level of BMI and

Citation:

Moreno-Domínguez S, in both samples, but the relationship between internalization and BD increased with

Rutsztein G, Geist TA, Pomichter EE BMI and was also stronger among Spaniards than Argentines. We argue that the

and Cepeda-Benito A (2019) Body

Mass Index and Nationality (Argentine

findings are congruent with theories that predict that economic development and

vs. Spanish) Moderate modernization contribute to normative female BD through internalization of the thin ideal

the Relationship Between

and that upward social comparisons or cognitive discrepancy between self-perceived

Internalization of the Thin Ideal

and Body Dissatisfaction: body image and the sociocultural thin ideal interacts synergistically with thin-ideal

A Conditional Mediation Model. internalization to increase BD.

Front. Psychol. 10:582.

doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00582 Keywords: body image, body dissatisfaction, thin ideal, eating disorders, internalization, conditional mediation

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 1 March 2019 | Volume 10 | Article 582

Moreno-Domínguez et al. BMI, Nationality and Body Dissatisfaction

INTRODUCTION internalization of the thin ideal and BD are consistently and often

twice the size of reported correlations between mere awareness of

Body dissatisfaction (BD), a negative evaluation of one’s the thin ideal (or perceived external pressure to be thin) and BD

appearance and body size, is thought to be a precursor of (see Cafri et al., 2005).

compensatory eating disorder symptoms such as restrictive The theory that Western values create a sociocultural

dieting, binge eating and purging, or excessive laxative use (e.g., environment that fosters female BD would predict that a

Attie and Brooks-Gunn, 1989; Stice et al., 1998). Although BD is population’s level of BD should correlate with the degree to

prevalent among individuals diagnosed with an eating disorder, which that population’s sociocultural milieu is, or becomes,

in the United States and other high-income countries some Westernized. This prediction is congruent with the observation

degree of BD and the desire to be thinner is more often the that along with the growing global influence of American

norm than the exception among adolescent girls and women. sociocultural values in the world (Mann, 2001), the eating

For instance, up to 90% of women attending college in the disorders literature has progressively reported an increasing

United States may report they would like to be slimmer than prevalence of female BD and disordered eating in non-Western

they are (e.g., Williams et al., 2001); in a United Kingdom countries (e.g., Forbes et al., 2012; Schulte and Thomas, 2013;

representative sample conducted by the Girlguiding organization Choi and Choi, 2016). Nonetheless, we also note that the effects

in 2009, 93% of adolescent girls said they would like to change of Western culture exposure and Western acculturation on

at least one thing about their physical appearance (as cited by eating-disorder risks could be heterogeneous and may differ

Verplanken et al., 2011). considerably across ethnically, culturally or nationally diverse

Sociocultural theorists postulate that this normative female groups (Becker et al., 2010) and across diverse samples from

BD is largely the result of Western (White American or Anglo- the same population (e.g., Warren et al., 2005). Additionally,

Saxon) cultural values and gendered societal norms characteristic culturally unique protective factors can also differentially impact

of modern, economically developed countries (DiNicola, 1990; the internalization-mediated effect of awareness of sociocultural

Brewis and McGarvey, 2000; Miller and Pumariega, 2001). In pressure to be thin on BD (Warren et al., 2005). Thus, it would

Westernized societies, physical appearance is fundamental to be important to test across culturally diverse samples the theory

the value and roles given to women, the thin female body that women’s exposure to Western sociocultural pressures to be

is equated with beauty and virtue, and beauty and virtue thin results in the internalization of a desire to be thin that

are presented as women’s path to success and life satisfaction consequently leads to BD.

(see Rodin et al., 1984; Stice, 1994; Stice et al., 2006). As Forbes et al. (2012) compared social pressure to be thin,

girls and women consume mass media messages and become internalization of the thin ideal, body-dissatisfaction and

aware of sociocultural pressures to look thin and fit, they eating disorder symptoms across undergraduate women from

are likely to begin embracing and seeking (i.e., internalizing) Argentina, Brazil and the United States Their results revealed that

the culturally prescribed and idealized female body (Stice, the United States sample reported significantly greater awareness

1994). In addition to media influences, Thompson et al. (1999) and internalization of the thin ideal, higher discrepancy between

postulated that peer and family pressure also contribute to their perceived vs. their desired body image (a measure of

women’s internalization of the thin ideal. This internalization BD), and more eating disorder symptoms than the Argentine

of the thin ideal is believed to cause BD as women compare and Brazilian samples. Although Forbes et al. (2012) speculated

themselves unfavorably against their unrealistic body-image that “cultural aspects” may “protect” Argentine and Brazilian

goals (e.g., Moreno-Domínguez et al., 2018). women from internalizing the “thin ideal,” these authors

There is considerable research linking the consumption of could not explain how culture prevented the internalization of

media exposure to BD (e.g., Bessenoff, 2006; Corning et al., the thin ideal.

2006; Grabe et al., 2008; Bonafini and Pozzilli, 2011), and Research conducted with Argentine and Spanish samples

experimentally controlled exposure to mainstream media images suggest that women from both countries present with

of thin models has been repeatedly shown to increase BD in considerable levels of normative BD, which could be driven, at

young women (e.g., Bessenoff, 2006; Moreno-Domínguez et al., least in part, by the internalization of social and cultural pressure

2018; see also Want, 2009). Moreover, the hypothesis that the to adhere to the Western, thin female ideal. For example,

internalization of the thin ideal mediates the relationship between up to 80% of adolescent girls from a Buenos Aires sample

awareness of the cultural ideal and body dissatisfaction has reported being dissatisfied with their weight (McArthur et al.,

considerable empirical support (e.g., Thompson et al., 1999; Stice, 2005). Similarly, many studies have reported strong evidence

2002; Fingeret and Gleaves, 2004; Warren et al., 2005; Shin et al., of normative BD (e.g., Gleaves et al., 2000; Warren et al., 2005)

2017; for a review see López-Guimerà et al., 2010). In addition, and internalization of the female thin ideal among Spaniards

empirical research suggests that sociocultural pressure to adhere (Lameiras Fernández et al., 2003; De Gracia et al., 2007; Ramos

to the thin ideal may lead to substantive BD only in individuals Valverde et al., 2010; Ramos et al., 2016). We only know of one

who report high levels of thin ideal internalization (Dittmar study that has compared BD across Argentines and Spaniards

and Howard, 2004; Dittmar et al., 2009; López-Guimerà et al., (Marrodán et al., 2008). These authors found that whereas both

2010). Correlational research further suggests that internalization Argentine and Spanish adolescent girls reported a general desire

of the thin ideal, rather than mere awareness of the ideal, is to be thinner, Spanish participants reported lower self-image

critical for the development of BD. That is, correlations between satisfaction than the Argentines. In a study that compared

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 2 March 2019 | Volume 10 | Article 582

Moreno-Domínguez et al. BMI, Nationality and Body Dissatisfaction

Argentine and Swedish adolescent girls, Swedes were more likely

than Argentines to report being “too fat” (Holmqvist et al., 2007).

Independent of BMI, these authors found that among those who

self-classified as being too fat, Swedish girls reported higher body

weight and body appearance dissatisfaction than Argentine girls

(Holmqvist et al., 2007).

Given the paucity of research on BD comparing Argentinian

and Spanish samples, we can only theorize about the extent to

which Western values of female thinness may have differentially

impacted women in two Spanish-speaking countries with

different sociocultural and economic milieus. For example,

if within a given population normative BD increases with

the population’s degree of exposure to modernization and

economic development (DiNicola, 1990), we can hypothesize

that normative BD and the underlying processes that lead to

its manifestation should be more entrenched among Spaniards

than Argentines. That is, we assume that historically Spain has

had a longer and more established exposure to modernization

and high economic development. For instance, the World

Bank has classified Spain as a “high-income” country every

year since they began to classify countries in 1988 by Gross

National Income per capita, while Argentina was assigned that

rank only in 2015 and 2018 (World Bank Data Help Desk,

2018). Therefore, we hypothesize that “nationality” (Spanish

vs. Argentine) may function as a moderator of the association

between the internalization of the thin ideal and its effect on

BD, as it seems to have been the case in the comparison

between Swedish and Argentine girls who self-classified as

being “too fat” but differed on the extent to which they

were dissatisfied with their body appearance and body weight

(Holmqvist et al., 2007).

Additionally, although exposure to the thin ideal may cause

BD through an internalization process, BD is a complex construct

that may develop differently not only from culture to culture,

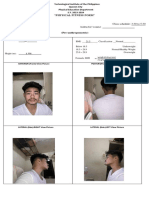

but also across individuals. That is, when we assert that FIGURE 1 | (A) Conceptual Conditional Mediation Model such as that

internalization of the thin ideal leads to BD we should not ignore Awareness of the thin ideal (X) predicts Body Dissatisfaction (BD) directly

the possibility that women may differ on the extent to which (X → Y ) and indirectly through Internalization of the thin ideal (X → M;

M → Y ). The model is conditional on Body Mass Index (BMI; W) and

this process is manifested. For instance, BMI correlates with nationality (Z). Age (C1 ) is a covariate. (B) Depicts the statistical model

(McCabe and Ricciardelli, 2003; Petrie et al., 2010; Laus et al., described in panel (A).

2011) and prospectively predicts (e.g., Stice and Whitenton, 2002;

Bearman et al., 2006; Clark and Tiggemann, 2008; Wojtowicz

and von Ranson, 2012; Quick et al., 2013) BD in adolescent

girls. BMI is also consistently associated with BD in samples similar levels of internalization, those with higher BMIs are more

of college students and adult women (e.g., Bulik et al., 2001; likely to experience greater self-discrepancy and thus higher BD

Williams et al., 2001; Warren et al., 2005; Dalley et al., 2009), than individuals with lower BMIs.

and there is empirical support suggesting BMI and BD share Our hypothesized model is depicted in Figure 1, the

risk factors, including heritability (Wade et al., 2011). Given the conceptual model is depicted in panel A and the statistical model,

well documented association and predictive relationship between with Age as a covariate, is depicted in panel B. We used an

BMI and BD, and the often tested and supported hypothesis that Argentine and a Spanish sample of young women to test a

BD is largely caused by a process of social comparison whereby conditional mediational model that predicts that the effects of

women repeatedly evaluate themselves negatively against the awareness of the thin ideal (X) on BD (Y) are mediated through

socially prescribed thin ideal (see Want, 2009), we posit that internalization of the thin ideal (X → M → Y). We further

BMI likely moderates the relationship between the internalization specify that the indirect effect component of internalization

of the thin ideal and BD. That is, if cognitive self-discrepancy to BD (M → Y) is conditional on BMI (W) and Nationality

between one’s ideal and perceived body image is the underlying (Z). We directionally predicted that whereas the mediational

mechanism that links internalization to BD (e.g., Bessenoff, model would replicate across countries, the paths MW → Y and

2006), it is reasonable to hypothesize that among individuals with MZ → Y would be significant. Examination of the interaction

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 3 March 2019 | Volume 10 | Article 582

Moreno-Domínguez et al. BMI, Nationality and Body Dissatisfaction

effects should reveal that the M → Y effect is more pronounced Measures

among participants with higher BMIs, as well as among Spaniards BMI

than Argentines. Participants reported their weight in kilograms and height in

meters. The BMI was calculated using the formula kg/m2 .

Whereas actual measurements of height and weight should

MATERIALS AND METHODS yield more accurate estimates of BMI, in our experience BMIs

calculated from either self-reported height and weight, or from

Participants measured height and weight are highly correlated (r2 and/or

We used a convenience sample of 499 young women (age = 18 to r > 0.98) and do not change found relationships between BMI

29) recruited from the student populations from the University and other variables (see also Olfert et al., 2018).

of Buenos Aires, Argentina (n = 290) and the University of

Jaen, Spain (n = 209). Research assistants recruited participants BSQ

by making in person announcements at the beginning or end The BSQ asks participants to report how they feel about their

class periods requesting female volunteers to participate in a appearance by answering 34 items that are scored in a six-

survey study about body image. Uncompensated volunteers point, Likert-type scale from never (1) to always (6). Total scores

attending group sessions of 30 to 40 students held in a large can range from 34 to 204, with scores above 104 being in the

classroom hall read and signed the informed consent form clinical range. The BSQ assesses general preoccupation with

and completed the questionnaires. Research assistants asked body shape and size, and fears of becoming or feeling fat. The

the participants to work individually and respond to the items measure has been shown to yield excellent reliability indices, to

without overthinking their answers, letting them know that there discriminate between eating disorder samples and controls, and

were neither correct nor incorrect answers as different women to be sensitive to treatment gains (Cooper et al., 1987; Zabinski

may have different experiences, perceptions or feelings about et al., 2001). Several investigations have used the Spanish version

questions asked. The internal review boards of both universities of the BSQ and reported adequate reliability and validity (e.g.,

approved the study as being compliant with the American Warren et al., 2008; Moreno et al., 2009). In the present study,

Psychological Association’s ethical principles for conducting internal reliability for the Argentinian (α = 0.96) and Spanish

research with human participants. (α = 0.98) scores were excellent.

Means, standard deviations and t-test comparisons between

the two samples for Age, BMI, Body Satisfaction Questionnaire SATAQ-4

(BSQ, Cooper et al., 1987) and the Awareness and Internalization The SATAQ-4 asks respondents to rate their agreement with 22

scales of the Sociocultural Attitudes Toward Appearance statements using a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (“definitely

Questionnaire-4 (SATAQ-4; Schaefer et al., 2015) scores are disagree”), to 5 (“definitely agree”). The SATAQ-4 can be divided

presented in Table 1. into two scales, one corresponding to 12 items that ask about

With regards to Age and BMI, the Argentinian sample was being aware of perceived pressure from family, peers, and

about 2 1/2 years and significantly older (M = 24.7; SD = 2.0) than the media to look thin or athletic (awareness/pressure scale;

the Spanish sample (M = 22.1; SD = 2.0), but the average BMI heretofore SATAQ-4A) and one corresponding to 10 items that

(kg/m2 ) was similar across Argentines (M = 22.35; SD = 3.88) ask about acceptance or self-imposed pressure to look thin or

and Spaniards (M = 22.59; SD = 3.83). Average BSQ scores were athletic (internalizing scale; heretofore SATAQ-4I). Psychometric

well below clinical levels in both samples but Spaniards scored evaluations of the SATAQ-4 report evidence of convergent

significantly higher (M = 87.02; SD = 42.11) than Argentines validity with various eating disorder and body dissatisfaction

(M = 74.13; SD = 29.90). Spaniards and Argentines scored measures, as well as high internal consistency scores in samples of

similarly on the Awareness (M = 25.97; SD = 9.93 vs. M = 25.53; English (Schaefer et al., 2015) and Spanish (Llorente et al., 2015)

SD = 9.89) and Internalization (M = 25.45; SD = 9.50 vs. speaking college students. In our sample, internal consistency was

M = 24.43; SD = 9.51) scales of SATAQ-4. excellent for both the SATAQ-4A and SATAQ-4I scores in both

samples (α = 0.89 to 0.91).

TABLE 1 | Means, standard deviations, and two-tailed t-test comparisons Analytic Approach

between the Argentine and Spanish samples for age, body mass index (BMI), thin

Mediation analysis allows investigators to test how an

ideal awareness (SATAQ-4A), thin ideal internalization (SATAQ-4I), and body

dissatisfaction (BSQ). independent variable X exerts a significant indirect effect

on a dependent variable Y by changing a third variable M, which

Spaniards (n = 209) Argentines (n = 290) in turn causes changes on Y (X → M → Y; see Figure 1A).

One of the most common methods used to test mediation

M SD M SD t (497) p<

models is the causal-steps strategy (Baron and Kenny, 1986),

Age 22.1 2.0 24.7 2.0 14.51 0.0001 which despite of its popularity has important conceptual and

BMI 22.59 3.83 22.35 3.88 −0.60 0.5526 power limitations (see MacKinnon et al., 2002; Preacher et al.,

SATAQ-4A 25.97 9.93 25.53 9.89 −0.48 0.6338 2007). Conceptually and mathematically sound alternatives to

SATAQ-AI 25.45 9.50 24.43 9.51 −1.15 0.2509 the causal-steps method include resampling or bootstrapping

BSQ 87.02 42.11 74.13 29.90 −3.95 0.0001 and product of coefficients strategies (Preacher and Selig, 2012;

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 4 March 2019 | Volume 10 | Article 582

Moreno-Domínguez et al. BMI, Nationality and Body Dissatisfaction

TABLE 2 | Regression results for the conditional mediation model depicted in Figure 1 while controlling for age.

Consequent

M (SATAQ-4I) Y (BSQ)

Antecedents Coefficient SE (HC1) p< Coefficient SE (HC1) p<

X (SATAQ-4A) a1 0.3568 0.0414 0.0001 c1 0.8771 0.1642 0.0001

M (SATAQ-4I) —— —— —— b1 2.0597 0.1459 0.0001

W (BMI) —— —— —— b2 2.4598 0.6197 0.0001

M×W —— —— —— b3 0.0908 0.0347 0.0094

Z (Arg = 0; Spa = 1) —— —— —— b4 3.9007 2.6989 0.1492

M× Z —— —— —— b5 0.6423 0.2610 0.0143

C1 (Age) a2 −0.5632 0.1727 0.0013 c2 −0.2009 0.5730 0.7262

Constant iM 3.9121 4.2854 0.3620 iY 61.5878 14.2620 0.0001

R2 = 0.425 R2 = 0.783

F(2, 360) = 48.7564; p < 0.0001 F(7, 355) = 82.7053; p < 0.0001

Hayes, 2018). In its simplest form, moderation analysis examines interactions with hypothesized moderators by producing and

when the relationship between a predictor X and a predicted plotting the predicted values of an outcome variable regressed

outcome Y depend, or is conditional on, a third variable, or on the predictor at different values of the moderator (Hayes,

moderator W; a question that is probed by testing whether the 2018). For interpretation, PROCESS provides standard errors,

regression weight of Y on X varies systematically as a function of p-values, confidence intervals for the direct effect coefficients, and

W (i.e., whether the hypothesized moderator W interacts with bootstrap confidence intervals for conditional indirect effects and

X to predict Y). Moderated mediation analysis simultaneously for conditional indirect effects pairwise contrasts. CIs that do not

tests how and when a relationship between an antecedent X and straddle zero are indicative of statistical significance.

an outcome Y occurs (see Hayes, 2018). Specifically, moderated For our analyses we used PROCESS v3.1, Model 16, which

mediation occurs when one or more relationship paths between allowed us to test a moderated mediation model such that

X, M, and Y (i.e., X → M, X → Y, or M → Y) in a mediation BD (Y) was regressed on Awareness of pressure to attain the

model (X → M → Y) interact with one or more moderators (e.g., Western ideal of beauty (X) and the covariate Age (C1 ) through

XW → M, MW → Y, MZ → Y, etc.) such that the relationship the Internalization of the ideal (M) (see Figure 1). Model 16

between the antecedent and the consequent (e.g., M → Y) is further specifies that the effect from the hypothesized mediating

contingent on the level of the moderator (see Preacher et al., or antecedent variable M (Internalization) to the outcome or

2007; Hayes, 2018). consequent variable Y (BD) is conditional on two moderating

Preacher, Hayes and their colleagues have provided various variables W (BMI) and Z (Argentines [0] vs. Spaniards [1]).

“macros” for SPSS and SAS that ease the task of carrying out

mediation and moderation analyses (e.g., Preacher and Hayes,

2004, 2008; Preacher et al., 2007; Hayes and Matthes, 2009). TABLE 3 | Indices of moderated mediation for BMI and nationality and conditional

indirect effects for the Argentine and Spanish samples at the 16, 50, and 84th

These and other similar tools have been integrated in PROCESS,

percentiles of the distribution of BMI scores.

a comprehensive tool that simplifies the testing of mediation,

moderated and moderated (conditional) mediation models Indices of

(Hayes, 2013, 2018). PROCESS uses path analysis modeling moderated

mediation

with ordinary least squares (OLS) and logistic regression. We

used SPSS v24.0 and the most recently available version of the Index SE LLCI ULCI

macro, PROCESS v3.1 (Hayes, 2018). To specify the statistical

Body max index (kg/m2 ) 0.0324 0.0138 0.0076 0.0618

model, we mean-centered the variables forming the interaction

Nationality (Arg = 0; Spa = 1) 0.2292 0.0986 0.0442 0.4335

terms (i.e., M, W, and Z), selected heteroscedasticity consistent

standard errors (HC1; see Hayes and Cai, 2007), and specified Conditional indirect effects

10,000 iterations to estimate bootstrap 95% coefficient confidence

BMI Percentile Nationality Effect SE LLCI ULCI

intervals (CIs; see Hayes, 2018). The use bootstrapping to

calculate CIs does not assume normally distributed indirect 16th Argentine 0.5230 0.0937 0.3492 0.7153

effects, provides a more accurate test of mediation effects than 16th Spanish 0.7522 0.1266 0.5212 1.0162

the causal-steps Sobel test (see Preacher et al., 2007), and allows 50th Argentine 0.5963 0.0965 0.4170 0.7954

for pairwise comparisons between coefficients of an antecedent 50th Spanish 0.8254 0.1240 0.5973 1.0847

variable at different values of a moderator (see Hayes, 2018). 84th Argentine 0.7137 0.1193 0.4963 0.9665

PROCESS also facilitates the visual inspection of significant 84th Spanish 0.9428 0.1357 0.6942 1.2289

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 5 March 2019 | Volume 10 | Article 582

Moreno-Domínguez et al. BMI, Nationality and Body Dissatisfaction

Significant interactions (Internalization by BMI; Internalization the ideal (a1 = 0.3568; p < 0.0001). This finding was evident

by Nationality) were examined by visualizing predicted values of while controlling for the effects of age, which was in turn

BSQ scores at the 16th, 50th and 84th percentiles of SATAQ-4I negatively associated with self-reported internalization of the

centered and BMI centered scores within the Argentine, as well thin ideal (a2 = -0.5632; p < 0.0013). That is, younger age was

as the Spanish sample (see Hayes, 2018). a risk factor for internalization of the thin deal. The results

also supported the hypothesized and often reported finding

that internalization contributes to BD, as the coefficient for

RESULTS internalization was significantly greater than zero (b1 = 2.0597,

p < 0.0001), even while controlling for the effects of awareness,

Table 2 displays the model’s summary information (see Figure 1), age, BMI, nationality, and the interaction terms formed by

including the regression coefficients, standard errors, and the product of internalization by BMI, and internalization by

p-values. The results were congruent with the hypothesis that nationality (see column “Y (BSQ)” in Table 2). It should be noted

greater awareness of the thin ideal increases internalization of that awareness (c1 = 0.8771; p < 0.0001) and BMI (b2 = 2.4598;

FIGURE 2 | Visual representation of the association between internalization (SATAQ-AI centered scores) and Body Dissatisfaction (BSQ scores) at each of the

probed BMI values in the Spanish and Argentine samples.

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 6 March 2019 | Volume 10 | Article 582

Moreno-Domínguez et al. BMI, Nationality and Body Dissatisfaction

FIGURE 3 | Visual representation of the association between internalization (SATAQ-AI centered scores) and Body Dissatisfaction (BSQ scores) in the Spanish

vis-à-vis the Argentine sample at each of the probed BMI values.

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 7 March 2019 | Volume 10 | Article 582

Moreno-Domínguez et al. BMI, Nationality and Body Dissatisfaction

p < 0.0001) were also significant predictors of BD, but neither body dissatisfaction. That is, awareness of the thin ideal or

age (c2 = -0.2009; p < 0.0001) nor nationality (b4 = 3.9007; SATAQ-4A scores predicted internalization of the thin ideal

p < 0.1492) predicted BD. Importantly, the interactions BMI (SATAQ-4I scores), and both awareness and internalization

by internalization (b3 = 0.908; p < 0.0094) and nationality scores predicted BD (BSQ scores) while controlling for each other

by internalization (b5 = 0.6423; p < 0.0143) were statistically and the model’s covariates and moderators: age, BMI, nationality,

significant, meaning both BMI and nationality moderated the BMI by internalization and nationality by internalization. The

relationship between internalization and BD. results are thus congruent with the belief that sociocultural

Significant interactions in the OLS regression model require milieus that promote an idealized standard of female beauty and

further scrutiny. To this effect, PROCESS generates an Index of virtue characterized by an unrealistically thin or athletic body

Moderated Mediation with bootstrap CIs that indicate how much shape foster female BD (e.g., Stice et al., 2006). This pressure

the mediated effect of awareness on BD through internalization to conform to the thin ideal of beauty originates from various

change by each unit of increment in the corresponding sources, including family members, and peer groups (Thompson

moderator. We found that both BMI and nationality significantly and Stice, 2001), although mass media channels are thought to be

moderated the indirect effect of awareness on BD through particularly powerful in promoting these ideals (Tiggemann et al.,

internalization of the thin ideal. That is, neither the bootstrap 2000; Shin et al., 2017).

95% CIs for the index of moderation for BMI, (Index = 0.0324; CI We anticipated that the effects of awareness of the thin

[0.0076, 0.0618]) nor for nationality (Index = 0.2292; CI [0.0442, ideal on BD would be mediated by internalization of the

0.4335]) straddle zero (see Table 3). These results mean that ideal in both Argentines and Spaniards, and we also predicted

the association between Internalization and BD was significantly that nationality would interact with internalization such

stronger at larger BMI values (see Figure 2) and more that the association between internalization and BD would

pronounced among Spaniards than Argentines (see Figure 3). be more pronounced in Spaniards than Argentines. We

PROCESS also allows to probe significant conditional based our prediction on the assumption that the Spanish

(moderated) indirect effects at each of different moderator values. sample belonged to a more economically modernized

In our case, we probed the relationship between internalization population than the Argentine sample (see DiNicola, 1990),

and BD for the Argentines (0) and Spaniard (1) participants an assumption we based on longstanding, per capita income

at BMIs corresponding to the 16, 50, and 84th percentiles. differences between the two countries (World Bank Data

Figure 2 provides the visual representation of the conditional Help Desk, 2018). The significant regression coefficient

indirect effects at each of the probed BMI values in both of the interaction between internalization and nationality,

samples. Figure 3 gives a visual representation of the conditional as well as the bootstrap CI of the index of moderated

indirect effects of Argentines vis-à-vis the Spaniards for each mediation support our directional prediction. Our results

of the BMI values. Table 3 shows that all of the conditional clearly show that the relationship or regression slope between

indirect effects with bootstrap CIs for the Argentine and internalization and BD was more pronounced in the Spanish

Spanish samples at each of the three probed BMI values than Argentine sample across participants with low, average

were significant as none of the CIs straddle zero. Table 4 and high BMIs. We note here also that the Spanish and

further shows pairwise contrasts that tested for conditional Argentine sample did not significantly differ on awareness

indirect effect differences across probed BMI values. Each of of the thin ideal, internalization of the thin ideal, or BMI.

the contrasts tested was statistically significant as none of the However, the Spanish sample reported significantly higher

CIs straddle zero. levels of BD that the Argentine sample, and Spaniards were

significantly younger than the Argentines. Given that BD

was regressed on awareness and internalization of the ideal

DISCUSSION while controlling for age, BMI and nationality, the interaction

between nationality and internalization explains why BD

We found robust support for the hypothesis that awareness scores were higher among Spaniards than Argentines. Thus,

of pressure from media, family and friends to look thin and whereas it is not unique that internalization of the thin ideal

athletic predicts BD dissatisfaction, and that this effect is partially mediated the predicted positive relationship between awareness

channeled through the effect of internalization of the ideal on of the thin ideal and BD (e.g., Warren et al., 2005), the

replication of the model in a Latin American sample, and the

demonstration that the model explains differences in average

TABLE 4 | Pairwise conditional indirect effect contrasts, standard errors, and 95% BD between two Spanish speaking samples from different

CIs across BMI percentile values within nationalities. continents with marked economic development differences

represents a theoretically important and novel contribution

BMI %tiles (Effect 1-Effect 2)

to the literature.

(nationality) = Contrast SE LLCI ULCI

We reasoned that the effect of internalization of the thin ideal

50th vs. 16th (Argentine) (0.5963-0.5230) = 0.0732 0.0313 0.0173 0.1396 on BD could differ not only across cultures (e.g., Warren et al.,

50th vs. 16th (Spanish) (0.8254-0.7522) = 0.0732 0.0313 0.0173 0.1396 2005) but also as a function of individual differences. Specifically,

84th vs. 50th (Argentine) (0.7137-0.5963) = 0.1174 0.0501 0.0277 0.2239 we predicted that BMI would moderate the relationship between

84th vs. 50th (Spanish) (0.9428-0.8254) = 0.1907 0.0814 0.0449 0.3635 internalization and BD. Our results support this prediction as

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 8 March 2019 | Volume 10 | Article 582

Moreno-Domínguez et al. BMI, Nationality and Body Dissatisfaction

evidenced by the significant interaction between internalization culture-bound theories of BD that conceptualize cultural context

and BMI, the CI of the index of moderation of the indirect effect, and cultural identity as having a fluid rather than an all or

and the significant pairwise contrast between the conditional none influence in the expression of psychological phenomena

moderation coefficients that compared the slopes of the (American Psychological Association, 2003). For example, the

association between internalization and BD at the 16th, 50th, absence of significant differences between samples on SATAQ-

and 84th percentiles of the distribution of BMI scores; a pattern 4A and SATAQ-4I scores suggested similar awareness and

of results replicated across the Spanish and Argentine samples. vulnerability to internalize the Western ideal of female beauty

Our findings are congruent with previous research showing that in both samples. On the other hand, the interaction between

BMI is robustly associated with BD (e.g., Dalley et al., 2009; internalization and nationality to predict BD reflects a stronger

Laus et al., 2011; Wojtowicz and von Ranson, 2012), and that relationship between internalization and BD in Spanish than

internalization of the thin ideal may trigger BD through a process Argentine participants. Whereas we noted historical economic

of social comparison (see Want, 2009), or cognitive discrepancy differences between Argentine and Spain, researchers could

between the current and desired thinner self (Bessenoff, 2006), hypothesize other culturally dependent variables that may explain

with the assumption being that the perceived-ideal discrepancy is the interaction between nationality and internalization to predict

likely greater among individuals with higher than lower BMIs. BD. The present study focused on risk factors that may cause

Although it is well known that both BMI and internalization and mediate the emergence of BD. Perhaps future research could

correlate with BD, not many studies have investigated whether focus on theorizing more complex conditional mediation models

BMI and internalization interact to predict BD. We are aware of BD that could include BD as an antecedent of other eating-

of a small, 2 (High/Low BMI) X 2 (High/Low Internalization) disorder symptomatology, and/or include hypothetical protective

study that reported a “marginal” interaction effect on BD factors such as personality variables or individual abilities as

scores (Graff et al., 2013). There is a second study that tested mediators or moderators of BD and eating disorder symptoms.

but did not find an interaction effect between internalization It is also important to note that whereas BMI appears to have

and BMI on BD (Mitchell et al., 2012). Thus, we believe the influenced the degree to which internalization was associated

present study is the first to test and report a moderating effect with BD, internalization predicted BD regardless of BMI. That

of BMI on the effect of awareness of the thin ideal on BD is, BMI emerged as an important individual factor that both

through internalization. correlated with BD and interacted with internalization of the thin

An important limitation of our findings is that our study is ideal to predict BD, with the relationship being stronger among

cross-sectional and longitudinal research is more appropriate to individuals with higher BMIs. Thus, future research could be

test moderated and mediated processes. Additionally, although aimed to understand the mechanisms or processes that govern

BD among young women is normative (Low et al., 2003), and the the positive and moderating relationship between BMI and BD.

prevalence of BD and eating disorders is no longer thought to Finally, our study may have applied implications to the extent

be circumscribed to White, Anglo-Saxon populations, we relied that future prevention or treatment research test interventions

on two convenience, university samples from two specific cities that aim to impact the various pathways that contribute

in two different countries. That is, our findings have limited to BD. For example, prevention interventions could aim to

generalizability to other ages, nationalities, or even Spaniards foster resilience against the internalization of the thin ideal,

and Argentines from other cities or regions. Conversely, our or treatments aimed to increase self-acceptance and reduce

methodology also bears a few strengths that enhance the extent internalization of the thin ideal. Prevention and treatment

to which our findings contribute uniquely and substantively. Our interventions could also explore or target the relationship and

OLS path analytic approach using bootstrapping and product interaction between BMI and BD to foster healthier, more

of coefficients calculations to test a moderated mediation model realistic views and acceptance of a larger range of body shapes and

represents notable advantages over the more traditional, causal sizes. For instance, Moreno-Domínguez et al. (2018), recently

step approach often used in psychological research (Preacher found that exposure to images of overweight models increased

et al., 2007). Additionally, we went beyond mere comparisons of positive self-image, mood and body satisfaction, and these effects

awareness, internalization, and BD averages across nationalities were larger in participants with healthier self-images. These

and examined whether a theoretically and empirically inspired authors speculated that increasing the representation of average-

mediation model replicated across nationalities, as well as size and plus-size models and actors in the fashion advertisement

whether nationality and BMI moderated the mediation model. and entertainment industries could decrease normative BD

Whereas the cross-sectional our results precludes us among girls and women.

from making causal inferences, our findings have important

theoretical implications for informing relationships that could

be investigated through longitudinal and experimental studies AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

aimed to examines causal mechanisms leading to BD. On

the one hand, we replicated in two Spanish speaking samples SM-D, GR, and AC-B designed the study. SM-D and GR collected

from two different continents the finding that awareness of the the data. AC-B conducted the analyses in close consultation

thin ideal is associated with BD through internalization of the with SM-D. SM-D and AC-B wrote the first draft of the

thin ideal. We qualified this result by showing that nationality manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the

moderated the risk of BD. This pattern of results supports final manuscript.

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 9 March 2019 | Volume 10 | Article 582

Moreno-Domínguez et al. BMI, Nationality and Body Dissatisfaction

REFERENCES analysis. Psychol. Women Q. 28, 370–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2004.

00154.x

American Psychological Association (2003). Guidelines on multi-cultural Forbes, G. B., Jung, J., Vaamonde, J. D., Omar, A., Paris, L., and Formiga, N. S.

education, training, research, practice, and organizational change for (2012). Body dissatisfaction and disordered eating in three cultures: Argentina,

psychologists. Am. Psychol. 58, 377–402. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.5.377 Brazil, and the US. Sex Roles 66, 677–694. doi: 10.1007/s11199-011-0105-3

Attie, I., and Brooks-Gunn, J. (1989). Development of eating problems in Gleaves, D. H., Cepeda-Benito, A., Williams, T. L., Cororve, M. B., Fernandez,

adolescent girls: a longitudinal study. Dev. Psychol. 25, 70–79. doi: 10.1037/ M. D. C., and Vila, J. (2000). Body image preferences of self and others: a

0012-1649.25.1.70 comparison of Spanish and American male and female college students. Eat.

Baron, R. M., and Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable Disord. 8, 269–282. doi: 10.1080/10640260008251236

distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical Grabe, S., Ward, L. M., and Hyde, J. S. (2008). The role of the media in body image

considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51, 1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51. concerns among women: a meta-analysis of experimental and correlational

6.1173 studies. Psychol. Bull. 134, 460–476. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.460

Bearman, S. K., Presnell, K., Martinez, E., and Stice, E. (2006). The skinny on Graff, K. A., Murnen, S. K., and Krause, A. K. (2013). Low-cut shirts and high-

body dissatisfaction: a longitudinal study of adolescent girls and boys. J. Youth heeled shoes: increased sexualization across time in magazine depictions of

Adolesc. 35, 229–241. doi: 10.1007/s10964-005-9010-9 girls. Sex Roles 69, 571–582. doi: 10.1007/s11199-013-0321-0

Becker, A. E., Fay, K., Agnew-Blais, J., Guarnaccia, P. M., Striegel-Moore, R. H., Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional

and Gilman, S. E. (2010). Development of a measure of ‘acculturation’ for Process Analysis: Methodology in the Social Sciences. New York, NY: Guilford

ethnic Fijians: methodologic and conceptual considerations for application Press.

to eating disorders research. Transcult. Psychiatry 47, 454–488. doi: 10.1177/ Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional

1363461510382153 Process Analysis Second Edition: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY:

Bessenoff, G. R. (2006). Can the media affect us? Social comparison, self- Guilford Press.

discrepancy, and the thin ideal. Psychol. Women Q. 30, 239–251. doi: 10.1111/j. Hayes, A. F., and Cai, L. (2007). Using heteroskedasticity-consistent standard error

1471-6402.2006.00292.x estimators in OLS regression: an introduction and software implementation.

Bonafini, B. A., and Pozzilli, P. (2011). Body weight and beauty: the changing face Behav. Res. Methods 39, 709–722. doi: 10.3758/bf03192961

of the ideal female body weight. Obesity Rev. 12, 62–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1467- Hayes, A. F., and Matthes, J. (2009). Computational procedures for probing

789X.2010.00754.x interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations.

Brewis, A. A., and McGarvey, S. T. (2000). Body image, body size, and Samoan Behav. Res. Methods 41, 924–936. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.3.924

ecological and individual modernization. Ecol. Food Nutr. 39, 105–120. doi: Holmqvist, K., Lunde, C., and Frisén, A. (2007). Dieting behaviors, body shape

10.1080/03670244.2000.9991609 perceptions, and body satisfaction: cross-cultural differences in argentinean

Bulik, C. M., Wade, T. D., Heath, A. C., Martin, N. G., Stunkard, A. J., and Eaves, and swedish 13-year-olds. Body Image 4, 191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2007.

L. J. (2001). Relating body mass index to figural stimuli : population-based 03.001

normative data for Caucasians. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 25, 1517–1524. Lameiras Fernández, M., Otero, M. C., Castro, Y. R., and Prieto, M. F. (2003).

doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801742 Hábitos alimentarios e imagen corporal en estudiantes universitarios sin

Cafri, G., Yamamiya, Y., Brannick, M., and Thompson, J. K. (2005). The influence trastornos alimentarios. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 3, 23–33.

of sociocultural factors on body image: a meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. 12, Laus, M. F., Costa, T. M. B., and Almeida, S. S. (2011). Body image

421–433. doi: 10.1093/clipsy/bpi053 dissatisfaction and its relationship with physical activity and body mass index

Choi, E., and Choi, I. (2016). The associations between body dissatisfaction, body in Brazilian adolescents. J. Bras. Psiquiatr. 60, 315–320. doi: 10.1590/s0047-

figure, self-esteem, and depressed mood in adolescents in the United States and 20852011000400013

Korea: a moderated mediation analysis. J. Adolesc. 53, 249–259. doi: 10.1016/j. Llorente, E., Gleaves, D. H., Warren, C. S., Pérez-de-Eulate, L., and

adolescence.2016.10.007 Rakhkovskaya, L. (2015). Translation and validation of a spanish version

Clark, L., and Tiggemann, M. (2008). Sociocultural and individual psychological of the sociocultural attitudes towards appearance questionnaire-4 (SATAQ-4).

predictors of body image in young girls: a prospective study. Dev. Psychol. 44, Int. J. Eat. Disord. 48, 170–175. doi: 10.1002/eat.22263

1124–1134. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.1124 López-Guimerà, G., Levine, M. P., Sánchez-Carracedo, D., and Fauquet, J. (2010).

Cooper, P. J., Taylor, M. J., Cooper, Z., and Fairburn, C. G. (1987). The development Influence of mass media on body image and eating disordered attitudes and

and validation of the body shape questionnaire. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 6, 485–494. behaviors in females: a review of effects and processes. Media Psychol. 13,

doi: 10.1002/1098-108X(198707)6:4<485::AID-EAT2260060405>3.0.CO;2-O 387–416. doi: 10.1080/15213269.2010.525737

Corning, A. F., Krumm, A. J., and Smitham, L. A. (2006). Differential social Low, K. G., Charanasomboon, S., Brown, C., Hiltunen, G., Long, K., Reinhalter, K.,

comparison processes in women with and without eating disorder symptoms. et al. (2003). Internalization of the thin ideal, weight and body image concerns.

J. Couns. Psychol. 53, 338–349. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.3.338 Soc. Behav. Pers. 31, 81–90. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2003.31.1.81

Dalley, S. E., Buunk, A. P., and Umit, T. (2009). Female body dissatisfaction after MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., and Sheets, V.

exposure to overweight and thin media images: the role of body mass index and (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening

neuroticism. Pers. Individ. Differ. 47, 47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2009.01.044 variable effects. Psychol. Methods 7, 83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.83

De Gracia, M., Marco, M., and Trujano, P. (2007). Factores asociados a la conducta Mann, M. (2001). Globalization is (among other things) transnational, inter-

alimentaria en preadolescents. Piscothema 19, 646–653. national and American. Sci. Soc. 65, 464–469. doi: 10.1521/siso.65.4.464.

DiNicola, V. F. (1990). Anorexia multiforme: self-starvation in historical and 17807

cultural context: part ii: anorexia nervosa as a culture-reactive syndrome. Marrodán, D., Montero-Roblas, V., Mesa, S., Pacheco, J. L., González, M.,

Transcult. Psychiatr. Res. Rev. 27, 245–286. doi: 10.1177/136346159002700401 Bejarano, I., et al. (2008). Realidad, percepción y atractivo de la imagen corporal:

Dittmar, H., Halliwell, E., and Stirling, E. (2009). Understanding the impact of condicionantes biológicos y socioculturales. Cuadernos Antropol. Etnografía 30,

thin media models on women’s body-focused affect: the roles of thin-ideal 15–28.

internalization and weight related self-discrepancy activation in experimental McArthur, L. H., Holbert, D., and Peña, M. (2005). An exploration of the attitudinal

exposure effects. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 28, 43–72. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2009.2 and perceptual dimensions of body image among male and female adolescents

8.1.43 from six latin american cities. Adolescence 40, 801–816.

Dittmar, H., and Howard, S. (2004). Ideal-body internalization and social McCabe, M. P., and Ricciardelli, L. A. (2003). Sociocultural influences on body

comparison tendency as moderators of thin media models’ impact on women’s image and body changes among adolescent boys and girls. J. Soc. Psychol. 143,

body focused anxiety. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 23, 768–791. doi: 10.1521/jscp.23.6. 5–26. doi: 10.1080/00224540309598428

768.54799 Miller, M. N., and Pumariega, A. J. (2001). Culture and eating disorders: a historical

Fingeret, M. C., and Gleaves, D. H. (2004). Sociocultural, feminist, and and cross-cultural review. Psychiatry 64, 93–110. doi: 10.1521/psyc.64.2.93.

psychological influences on women’s body satisfaction: a structural modeling 18621

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 10 March 2019 | Volume 10 | Article 582

Moreno-Domínguez et al. BMI, Nationality and Body Dissatisfaction

Mitchell, S. H., Petrie, T. A., Greenleaf, C. A., and Martin, S. B. (2012). Moderators Stice, E., Orjada, K., and Tristan, J. (2006). Trial of a psychoeducational eating

of the internalization–body dissatisfaction relationship in middle school girls. disturbance intervention for college women: a replication and extension. Int.

Body Image 9, 431–440. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.07.001 J. Eat. Disord. 39, 233–239. doi: 10.1002/eat.20252

Moreno, S., Warren, C. S., Rodríguez, S., Fernández, M. C., and Cepeda-Benito, A. Stice, E., and Whitenton, K. (2002). Risk factors for body dissatisfaction in

(2009). Food cravings discriminate between anorexia and bulimia nervosa. adolescent girls: a longitudinal investigation. Dev. Psychol. 38, 669–678. doi:

implications for “success” versus “failure” in dietary restriction. Appetite 52, 10.1037/0012-1649.38.5.669

588–594. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.01.011 Thompson, J. K., Heinberg, L. J., Altabe, M., and Tantleff-Dunn, S. (1999).

Moreno-Domínguez, S., Servián-Franco, F., Reyes, D. P., and Cepeda-Benito, A. Interpersonal factors: Peers, Parents, Partners, and Perfect Strangers. Exacting

(2018). Images of thin and plus-size models produce opposite effects on beauty: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment of Body Image Disturbance; Exacting

women’s body image, body dissatisfaction, and anxiety. Sex Roles doi: 10.1007/ Beauty: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment of Body Image Disturbance.

s11199-018-0951-3 [E-pub ahead of print]. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 175–207. doi: 10.1037/

Olfert, M., Barr, M., Charlier, C., Famodu, O., Zhou, W., Mathews, A., et al. (2018). 10312-006

Self-Reported vs. measured height, weight, and BMI in young adults. Int. J. Thompson, J. K., and Stice, E. (2001). Thin-ideal internalization: mounting

Environ. Res. Public Health 15:2216. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15102216 evidencce for a new risk factor for body-image disturbance and eating

Petrie, T. A., Greenleaf, C., and Martin, S. (2010). Biopsychosocial and physical pathology. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 10, 181–183. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.00144

correlates of middle school boys’ and girls’ body satisfaction. Sex Roles 63, Tiggemann, M., Gardiner, M., and Slater, A. (2000). “I would rather be a size

631–644. doi: 10.1007/s11199-010-9872-5 10 than have straight A’s”: a focus group study of adolescent girls’ wish to be

Preacher, K. J., and Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating thinner. J. Adolesc. 23, 645–659. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0350

indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Verplanken, B., and Tangelder, Y. (2011). No body is perfect: the significance of

Comput. 36, 717–731. doi: 10.3758/BF03206553 habitual negative thinking about appearance for body dissatisfaction, eating

Preacher, K. J., and Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for disorder propensity, self-esteem and snacking. Psychol. Health 26, 685–701.

assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. doi: 10.1080/08870441003763246

Res. Methods 40, 879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 Wade, T. D., Zhu, G., and Martin, N. G. (2011). Undue influence of weight and

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., and Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated shape: Is it distinct from body dissatisfaction and concern about weight and

mediation hypotheses: theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behav. shape? Psychol. Med. 41, 819–828. doi: 10.1017/s0033291710001066

Res. 42, 185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316 Want, S. C. (2009). Meta-analytic moderators of experimental exposure to media

Preacher, K. J., and Selig, J. P. (2012). Advantages of Monte Carlo confidence portrayals of women on female appearance satisfaction: social comparisons as

intervals for indirect effects. Commun. Methods Meas. 6, 77–98. doi: 10.1080/ automatic processes. Body Image 6, 257–269. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.07.008

19312458.2012.679848 Warren, C. S., Cepeda-Benito, A., Gleaves, D. H., Moreno, S., Rodriguez, S.,

Quick, V., Eisenberg, M. E., Bucchianeri, M. M., and Neumark-Sztainer, D. Fernandez, M. C., et al. (2008). English and spanish versions of the body shape

(2013). Prospective predictors of body dissatisfaction in young adults: 10- questionnaire: measurement equivalence across ethnicity and clinical status.

year longitudinal findings. Emerg. Adulthood 1, 271–282. doi: 10.1177/ Int. J. Eat. Disord. 41, 265–272. doi: 10.1002/eat.20492

2167696813485738 Warren, C. S., Gleaves, D. H., Cepeda-Benito, A., del, C. F., and Rodriguez-Ruiz, S.

Ramos, P., Rivera, F., Pérez, R. S., Lara, L., and Moreno, C. (2016). Diferencias de (2005). Ethnicity as a protective factor against internalization of a thin ideal and

género en la imagen corporal y su importancia en el control de peso. Escritos body dissatisfaction. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 37, 241–249. doi: 10.1002/eat.20102

Psicol. 9, 42–50. doi: 10.5231/psy.writ.2015.1409 Williams, T. L., Gleaves, D. H., Cepeda-Benito, A., Erath, S. A., and Cororve, M. B.

Ramos Valverde, P., Rivera de los Santos, F. J., Rodríguez, M., and Carmen, M. (2001). The reliability and validity of a group-administered version of the body

(2010). Diferencias de sexo en imagen corporal, control de peso e Índice de image assessment. Assessment 8, 37–46. doi: 10.1177/107319110100800104

Masa Corporal de los adolescentes españoles. Psicothema 22, 77–83. Wojtowicz, A. E., and von Ranson, K. M. (2012). Weighing in on risk factors for

Rodin, J., Silberstein, L., and Striegel-Moore, R. (1984). Women and weight: a body dissatisfaction: a one-year prospective study of middle-adolescent girls.

normative discontent. Nebraska Symp. Motiv. 32, 267–307. Body Image 9, 20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.07.004

Schaefer, L. M., Burke, N. L., Thompson, J. K., Dedrick, R. F., Heinberg, L. J., World Bank Data Help Desk (2018). World Bank Country, and. (Lending)

Calogero, R. M., et al. (2015). Development and validation of the sociocultural Groups: Historical Classification by Income in XLS Format. Avaialble at: https:

attitudes towards appearance questionnaire-4 (SATAQ-4). Psychol. Assess. 27, //datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519

54–67. doi: 10.1037/a0037917 Zabinski, M. F., Pung, M. A., Wilfley, D. E., Eppstein, D. L., Winzelberg, A. J.,

Schulte, S. J., and Thomas, J. (2013). Relationship between eating pathology, body Celio, A., et al. (2001). Reducing risk factors for eating disorders: targeting

dissatisfaction and depressive symptoms among male and female adolescents in at-risk women with a computerized psychoeducational program. Int. J. Eat.

the United Arab Emirates. Eat. Behav. 14, 157–160. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013. Disord. 29, 401–408. doi: 10.1002/eat.1036

01.015

Shin, K., You, S., and Kim, E. (2017). Sociocultural pressure, internalization, BMI, Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors declare that the research was

exercise, and body dissatisfaction in korean female college students. J. Health conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could

Psychol. 22, 1712–1720. doi: 10.1177/1359105316634450 be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Stice, E. (1994). Review of the evidence for a sociocultural model of bulimia nervosa

and an exploration of the mechanisms of action. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 14, 633–661. Copyright © 2019 Moreno-Domínguez, Rutsztein, Geist, Pomichter and Cepeda-

doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(94)90002-7 Benito. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Stice, E. (2002). Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: a meta-analytic Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in

review. Psychol. Bull. 128, 825–848. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.825 other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s)

Stice, E., Mazotti, L., Krebs, M., and Martin, S. (1998). Predictors of adolescent are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance

dieting behaviors: a longitudinal study. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 12, 195–205. with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted

doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.12.3.195 which does not comply with these terms.

Frontiers in Psychology | www.frontiersin.org 11 March 2019 | Volume 10 | Article 582

You might also like

- The Influence of Sociocultural Factors On Body Image: A Meta-AnalysisNo ratings yetThe Influence of Sociocultural Factors On Body Image: A Meta-Analysis13 pages

- The Sociocultural Attitudes Towards AppearanceNo ratings yetThe Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance12 pages

- Cahill, Mussap - 2007 - Emotional Reactions Following Exposure To Idealized Bodies Predict Unhealthy Body Change Attitudes and Behaviors-AnnotatedNo ratings yetCahill, Mussap - 2007 - Emotional Reactions Following Exposure To Idealized Bodies Predict Unhealthy Body Change Attitudes and Behaviors-Annotated9 pages

- Stern JM. Transcultural Aspects of Eating Disorders and Body Image Disturbance. NORDIC JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRY 2018, VOL. 72, NO. S1, S23-S26No ratings yetStern JM. Transcultural Aspects of Eating Disorders and Body Image Disturbance. NORDIC JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRY 2018, VOL. 72, NO. S1, S23-S265 pages

- Ideal Body Stereotype Internalization and Sociocultural Attitudes Towards AppearanceNo ratings yetIdeal Body Stereotype Internalization and Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance10 pages

- I'Ll Have What She's Having - How Social InfluenNo ratings yetI'Ll Have What She's Having - How Social Influen12 pages

- Registro Del Proceso de Selección de Estudios - PRISMANo ratings yetRegistro Del Proceso de Selección de Estudios - PRISMA59 pages

- An Integrative Affect Regulation Process Model of Internalized Weight Bias and Intuitive Eating in College WomenNo ratings yetAn Integrative Affect Regulation Process Model of Internalized Weight Bias and Intuitive Eating in College Women10 pages

- Body Image Change and Improved Eating Self-Regulation in A Weight Management Intervention in WomenNo ratings yetBody Image Change and Improved Eating Self-Regulation in A Weight Management Intervention in Women11 pages

- Research Proposal Plan AnushkaJoshi 1202724No ratings yetResearch Proposal Plan AnushkaJoshi 12027247 pages

- Bouncing Back With Bliss Nurturing Body Image and Embracing Intuitive Eating in The Postpartum A Cross-Sectional Replication StudyNo ratings yetBouncing Back With Bliss Nurturing Body Image and Embracing Intuitive Eating in The Postpartum A Cross-Sectional Replication Study16 pages

- Jennifer S. Mills - Thomson Model of BINo ratings yetJennifer S. Mills - Thomson Model of BI18 pages

- Physical Activity, Eating Behavior, and Body Image Perception Among University StudentsNo ratings yetPhysical Activity, Eating Behavior, and Body Image Perception Among University Students9 pages

- Development and Initial Psychometric Evaluation of The Body Image Matrix of Thinness and Muscularity - Female BodiesNo ratings yetDevelopment and Initial Psychometric Evaluation of The Body Image Matrix of Thinness and Muscularity - Female Bodies12 pages

- Reed Et Al (1991) - Development and Validation of The Physical Appearance State and Trait Anxiety Scale (PASTAS)No ratings yetReed Et Al (1991) - Development and Validation of The Physical Appearance State and Trait Anxiety Scale (PASTAS)10 pages

- A Study On The Relationship Between Mindful Eating, Eating Attitudes and Behaviors and Abdominal Obesity in Adult WomenNo ratings yetA Study On The Relationship Between Mindful Eating, Eating Attitudes and Behaviors and Abdominal Obesity in Adult Women5 pages

- Evaluating The Impact of A Brief HealthNo ratings yetEvaluating The Impact of A Brief Health22 pages

- Relationship Between Body Dissatisfaction, Depression and Anxiety Among Young AdultsNo ratings yetRelationship Between Body Dissatisfaction, Depression and Anxiety Among Young Adults19 pages

- Relationships Between Dissatisfaction With Specific Body Characteristics and The Sociocultural Attitudes Toward ..No ratings yetRelationships Between Dissatisfaction With Specific Body Characteristics and The Sociocultural Attitudes Toward ..7 pages

- Effects of Self-Esteem and Depression On Abnormal Eating Behavior Among Korean Female College Students Mediating Role of Body DissatisfactionNo ratings yetEffects of Self-Esteem and Depression On Abnormal Eating Behavior Among Korean Female College Students Mediating Role of Body Dissatisfaction8 pages

- Weight Management, Calorie Intake and BodyNo ratings yetWeight Management, Calorie Intake and Body8 pages

- Implicit Beliefs About Ideal Body Image Predict Body Image DissatisfactionNo ratings yetImplicit Beliefs About Ideal Body Image Predict Body Image Dissatisfaction9 pages

- Cuestionario de Actitudes Socioculturales Hacia La Apariencia (SATAQ-4) - Población EspañolaNo ratings yetCuestionario de Actitudes Socioculturales Hacia La Apariencia (SATAQ-4) - Población Española7 pages

- Learning Activity 2. Formulation of Hypotheses and Determination of Variables, Population, and Research Design.No ratings yetLearning Activity 2. Formulation of Hypotheses and Determination of Variables, Population, and Research Design.7 pages

- The Presence of Personality Traits of Borderline PNo ratings yetThe Presence of Personality Traits of Borderline P2 pages

- Implicit Measures of Actual Versus Ideal Body Image: Relations With Self-Reported Body Dissatisfaction and Dieting BehaviorsNo ratings yetImplicit Measures of Actual Versus Ideal Body Image: Relations With Self-Reported Body Dissatisfaction and Dieting Behaviors14 pages

- WEEK11 Repeated Exposure To The Thin Ideal and Implications For The SelfNo ratings yetWEEK11 Repeated Exposure To The Thin Ideal and Implications For The Self8 pages

- Sociology Health Illness - 2020 - Oude Groeniger - How Does Cultural Capital Keep You Thin Exploring Unique Aspects ofNo ratings yetSociology Health Illness - 2020 - Oude Groeniger - How Does Cultural Capital Keep You Thin Exploring Unique Aspects of19 pages

- Articles: Hanna Creese, Sonia Saxena, Dasha Nicholls, Ana Pascual Sanchez, and Dougal HargreavesNo ratings yetArticles: Hanna Creese, Sonia Saxena, Dasha Nicholls, Ana Pascual Sanchez, and Dougal Hargreaves13 pages

- The Role of Mediterranean Diet and Exercise On Obesity-Related Body Dissatisfaction and Eating Disturbances.No ratings yetThe Role of Mediterranean Diet and Exercise On Obesity-Related Body Dissatisfaction and Eating Disturbances.20 pages

- Diet Optimization Using Linear ProgrammingNo ratings yetDiet Optimization Using Linear Programming8 pages

- LAB #1 - Measurement & Conversions WorksheetNo ratings yetLAB #1 - Measurement & Conversions Worksheet3 pages

- The Effects of Body Mass Index On Outcomes For PatNo ratings yetThe Effects of Body Mass Index On Outcomes For Pat10 pages

- Epidemiology of Ovarian Cancer: A ReviewNo ratings yetEpidemiology of Ovarian Cancer: A Review24 pages

- Unified First Quarterly Assessment in MAPEH 10100% (1)Unified First Quarterly Assessment in MAPEH 1013 pages

- Pereira Da Silva 2023 Sensory and Muscular Functions of The Pelvic Foor in Women With EndometriosisNo ratings yetPereira Da Silva 2023 Sensory and Muscular Functions of The Pelvic Foor in Women With Endometriosis8 pages

- A Guide To Obesity and The Metabolic Syndrome Origins and Treatment - 1st Edition Scribd PDF Download100% (13)A Guide To Obesity and The Metabolic Syndrome Origins and Treatment - 1st Edition Scribd PDF Download14 pages

- MAPEH 4 Q1-W3 Matatag Curriclum DLL 2025-2026No ratings yetMAPEH 4 Q1-W3 Matatag Curriclum DLL 2025-202610 pages