Platform Power and Policy Fragility: Rethinking Public Accountability in India’s Digital

Democracy

Abstract

Digital platforms now mediate core functions of Indian democracy, from elections to civic

discourse to policy communication. While this offers new efficiencies, it also reveals gaps in

regulatory frameworks, democratic oversight, and institutional accountability. This paper argues

that India’s public policy ecosystem is underprepared for the structural challenges posed by

platform-mediated governance. Drawing from political science concepts of power, legitimacy,

and institutional design, the paper examines how digital platforms reshape state-citizen relations

and calls for a policy framework rooted in democratic accountability, not techno-solutionism.

1. Introduction: Platforms as Political Institutions

Digital platforms are no longer neutral communication tools. In India, companies like Meta,

Google, and X influence elections. They shape civic discourse and mediate public messaging.

Yet, they are governed more by corporate logic than democratic norms. This creates a deep

governance gap. Public expectations of accountability are high. But institutional control over

platforms is weak. From a public policy view, this is a regulatory failure. From a political

science angle, it signals a power shift. Authority is moving from elected institutions to digital

infrastructures (Banaji & Bhat, 2021).

Contemporary political science research sees platforms as governance actors (Gorwa & Garton

Ash, 2020; Bietti, 2021). They exercise authority, shape norms, and mediate rights. This aligns

with theories of delegated governance and regulatory capitalism (Kalyanpur, 2022; Zuboff,

2020). Platforms are private infrastructures with public functions. Yet they are rarely subjected

to democratic scrutiny (Suzor, 2021; Marsden, 2021). In India, this mismatch is particularly

stark. A vibrant digital public sphere has emerged, yet without institutional safeguards (Jain &

Ranjan, 2022). Content takedowns, algorithmic bias, and data monopolies undermine democratic

deliberation (Mukherjee, 2023; Sharma, 2023). Platforms operate as transnational entities with

uneven obligations (Chaudhary, 2022). Meanwhile, the state increasingly relies on platforms for

service delivery and communication (Khera, 2021; Ramachandran, 2022). This creates

dependency without accountability. During the COVID-19 crisis, platforms shaped access to

vaccines, relief, and information (Gupta et al., 2021). Their failures had real-world harms.

Theoretically, this paper draws from deliberative democracy (Dryzek, 2022), power analysis

(Fuchs, 2021), and public accountability (Mulgan, 2022). It considers how informational power

(Napoli, 2022), infrastructure governance (Plantin & Punathambekar, 2021), and algorithmic

control (Just & Latzer, 2021) reshape political agency. These frameworks help assess how

platforms affect Indian democracy.

Scholars warn of techno-solutionism and the erosion of political institutions (König &

Wenzelburger, 2022; Eubanks, 2021). Others emphasize the need for structural reforms, not just

reactive regulation (Pasquale, 2021; Gillespie, 2021). This paper contributes to this growing

debate by focusing on India’s unique institutional and democratic context.

�The paper proceeds in six parts. Section 2 examines the crisis of accountability. Section 3

presents a political science framework for analyzing platform power. Section 4 discusses

regulatory and policy options. Section 5 uses case studies to illustrate key tensions. The final

section argues for institutional reform rooted in democratic values.

2. The Crisis of Democratic Accountability

2.1 Weak Institutional Oversight and Legal Gaps

India’s digital governance system suffers from outdated legal foundations. Section 79 of the IT

Act, central to intermediary protection, was reinterpreted by the Supreme Court in Shreya

Singhal v. Union of India (2015). It mandated takedowns only with valid court or government

orders, reinforcing free speech rights (Singhal, 2015; Bhandari & Bhargava, 2022). However,

the decision left room for procedural ambiguities (Just & Latzer, 2021). Section 66A was

declared unconstitutional for being vague and overbroad (MouthShut.com v. Union of India,

2015).

Despite these rulings, India’s legal structure still lacks clarity. The IT Rules 2021 imposed heavy

obligations on platforms without adequate parliamentary oversight (Ghosh, 2021; IFF, 2022).

The definitions of "due diligence" and "content moderation" remain broad (ORF, 2023; Mulgan,

2022). This allows for executive overreach, as platforms become quasi-regulators (Suzor, 2021;

Gorwa & Garton Ash, 2020). Courts have largely deferred to executive discretion in digital

matters (Kapur, 2023).

Globally, countries like Germany have passed transparent laws like the NetzDG, which mandates

content moderation disclosures (Tworek & Leerssen, 2021). In contrast, India’s opaque

executive rule-making undermines legal predictability and user rights (Plantin & Punathambekar,

2021).

2.2 Internet Shutdowns as Accountability Failures

The Supreme Court in Anuradha Bhasin v. Union of India (2020) ruled that internet access is

essential for freedom of expression. It held that indefinite shutdowns are unconstitutional,

requiring periodic review and publication of shutdown orders (Anuradha Bhasin, 2020; APC,

2020). However, implementation has been inconsistent. Shutdowns in Kashmir and Manipur

extended beyond judicial scrutiny (Time, 2023; Srivastava, 2024).

Rule 2A of the 2017 Suspension Rules now caps shutdowns at 15 days, yet states rarely publish

orders or comply with review mechanisms (Reddit Data, 2021; Access Now, 2023). Platforms

and civil society have little recourse (Internet Freedom Foundation, 2024).

Compared globally, India leads in the number of internet shutdowns (Access Now, 2024).

Democracies like the UK or Germany rarely resort to such extreme measures. The EU’s General

Court has held that network shutdowns must pass proportionality tests (Council of the EU v.

PKK, 2022). India’s high frequency shutdowns reflect legal fragility and democratic regression

(Khan, 2023; Mehta, 2024).

�2.3 Fragmented Regulatory Response

Multiple ministries in India, MeitY, MIB, MHA, regulate digital platforms, leading to

fragmented policy outcomes (Sharma, 2023; Ramachandran, 2022). During crises like COVID-

19, overlapping jurisdictions created confusion around misinformation management and e-

governance tools (Gupta et al., 2021; Jain, 2023).

There is no central digital regulator similar to Ofcom in the UK or the Digital Services

Coordinator in the EU (EDPS, 2022). This impedes coordinated responses to content

moderation, algorithmic bias, and misinformation (Khera, 2021; Singh & Mehrotra, 2023). The

absence of inter-agency cooperation leaves platforms unchecked and accountability diminished

(Mukherjee, 2023).

Internationally, Germany’s Federal Office for Justice enforces transparency, while South Korea

has a robust data protection authority with real-time enforcement powers (Park & Kim, 2023).

India’s institutional vacuum leaves democratic safeguards under threat.

2.4 Platform Power Without Democratic Legitimacy

Platforms exercise de facto governance. They curate speech, remove content, and mediate public

discourse (Balkin, 2022; Banaji & Bhat, 2021). India’s legal regime has failed to create

accountability structures for such immense influence. While the EU’s Digital Services Act

mandates algorithmic transparency, India lacks any statutory framework to audit or challenge

content curation systems (Napoli, 2022; Dryzek, 2022). Indian courts have not adjudicated key

issues like algorithmic amplification or shadow banning. The absence of precedent means

platforms self-regulate with impunity (Fuchs, 2021; Rao & Mehrotra, 2023).

Cases like WhatsApp v. Union of India (2021) on traceability are pending, leaving end-to-end

encryption in limbo. Meanwhile, public discourse is shaped by opaque, privately controlled

systems (Balkin, 2021; Kapoor, 2023).

Comparatively, Brazil’s Marco Civil and the proposed PL2630 bill aim to enforce transparency

obligations on digital intermediaries (Doneda & Monteiro, 2022). Australia mandates fair news

bargaining through public institutions. These legal innovations balance platform power with

democratic oversight.

India must move toward comprehensive reform. Without institutional transparency and a rights-

based digital framework, the crisis of democratic accountability will deepen.

3. Political Science Framework: Platforms as Power Nodes

3.1 Power Without Responsibility

Robert Dahl’s theory of polyarchy offers useful insights (Dahl, 1989). He argued democracy

relies on dispersed centers of power. Today’s platforms are unelected but highly influential

�(Napoli, 2022). They filter speech, set agendas, and shape opinion (Just & Latzer, 2021). Yet

they lack public scrutiny and institutional accountability (Gorwa & Garton Ash, 2020).

Policy decisions by platforms evade democratic review (Klonick, 2020). Their terms of service

are not publicly debated (Suzor, 2021). Courts rarely intervene in content moderation choices

(Douek, 2021). In India, platform rules often override national priorities (Bhatia, 2022). There’s

no legislative oversight of these digital powers (Rajadhyaksha, 2023).

This power-responsibility gap erodes democratic legitimacy (Fuchs, 2021). Platforms act as

norm-setters without accountability structures (Plantin & Punathambekar, 2021). They remove

content arbitrarily, often favoring state or corporate actors (Chakravartty et al., 2020; Bhuyan,

2021).

Elections are now shaped by digital speech. But platforms are not bound by electoral codes (Rao,

2022). Public interest groups lack tools to audit these systems (Kaye, 2021). As power becomes

opaque, democracy loses its grounding (Wagner, 2023).

3.2 Informational Asymmetry

Platforms personalize news and content using opaque algorithms (Tufekci, 2022). Users see what

the system selects, not what’s vital (Bennett & Livingston, 2021). This creates information

asymmetry—users don’t know what they miss (Napoli, 2022).

Bachrach and Baratz’s “second face of power” applies well here (1962). Platforms decide which

voices surface and which vanish (Pasquale, 2021). Some issues gain visibility; others are buried

(Zuboff, 2020).

This shapes democratic priorities invisibly (Sunstein, 2022). Disinformation is promoted if it

drives clicks (Guess et al., 2021). Controversy sells; accuracy suffers (Pennycook & Rand,

2020). Users are trapped in filter bubbles that distort reality (Flaxman et al., 2021).

Political actors exploit these tools to micro-target voters (Persily & Tucker, 2020). This

undermines collective debate (Ananny, 2020). Users receive curated truths, not pluralistic

discourse (Gillespie, 2020).

Judicial remedies are unclear. Courts lack capacity to assess algorithmic harm (Patel, 2023).

Regulators struggle to understand platform design (De Gregorio, 2022).

India’s policy on misinformation remains reactive and fragmented (Chaudhuri, 2023). Platform

opacity makes oversight near impossible (Digital Asia Hub, 2022).

3.3 Structural Bias

Algorithms are not neutral. They encode dominant cultural values (Eubanks, 2021).

Marginalized voices are sidelined by design (Noble, 2020). Platforms reward popularity, not

diversity (Crawford & Paglen, 2021).

�Majoritarian narratives dominate search results (Banaji & Bhat, 2021). Hate speech often goes

viral; dissent is flagged (Nair, 2022). Sensational content thrives, silencing nuance (Papacharissi,

2021).

This reshapes the digital public sphere (Dryzek, 2022). Democracy needs dialogue—but

algorithms favor division (Barrett, 2021).

Deliberative ideals suffer in polarized feeds (Habermas, 2020). Youth are radicalized through

echo chambers (Ghosh & Scott, 2022). Gendered abuse online discourages female participation

(UN Women, 2021).

Platforms lack inclusive design. Content moderation fails local context (Tripathi & Singh, 2023).

AI tools often misidentify dialects and minorities (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2023).

Structural bias reflects offline inequalities. Dalit voices face disproportionate takedowns

(Teltumbde, 2022). Adivasi activism is flagged more than mainstream content (Scroll.in, 2023).

India’s digital governance fails to counter these trends (Sinha, 2022). There’s no requirement for

algorithmic audits or fairness checks (Rajagopal, 2024).

Without correction, platforms entrench social hierarchies (Sen, 2021). This threatens democratic

participation and representation (Chhibber, 2023).

3.4 Synthesis: Global Models of Platform Accountability

The governance of digital platforms is a global challenge. While India grapples with policy

fragility, other democracies offer instructive contrasts. Comparing India with the European

Union (EU) and the United States (US) reveals varied approaches to democratic accountability,

institutional oversight, and the structural role of platforms in public life.

The EU Model: Proactive Regulation and Rights-Based Oversight

The European Union has emerged as a global leader in digital platform regulation. It has

embraced rights-based governance with strong institutional safeguards. The Digital Services

Act (DSA) and Digital Markets Act (DMA) are landmark instruments that mandate

transparency, algorithmic audits, and due process in content moderation (De Gregorio &

Morozova, 2023; Keller, 2022).

The DSA requires platforms to publish risk assessments and engage independent audits (van

Hoboken & Ó Fathaigh, 2021). It empowers users to contest takedowns and misinformation

labels (Coche, 2023). This strengthens democratic accountability by embedding public oversight

into platform governance (Bradford, 2020).

Moreover, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) ensures privacy rights and

informational autonomy (Tzanou, 2021). European courts have upheld these protections,

�including the right to be forgotten (European Court of Justice, 2014). These legal instruments

reduce asymmetries of power between users and platforms (Floridi, 2021).

The EU treats platforms as quasi-public utilities with public obligations (Helberger et al., 2022).

This model represents “power with responsibility,” setting a normative standard for digital

democracies (Smuha & Véliz, 2023).

The US Model: Market-Driven Governance with Fragmented Oversight

The United States, by contrast, relies on market-based regulation and judicial restraint. It

protects platform immunity under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (Zeran v.

AOL, 1997), enabling broad content moderation powers without liability (Klonick, 2020).

While the First Amendment ensures speech freedom, it also limits government intervention

(Balkin, 2021). Courts have avoided enforcing moderation standards, leaving platforms to self-

regulate (Citron & Wittes, 2021). Transparency is voluntary, and algorithmic accountability

remains minimal (Gillespie, 2022).

However, recent developments show cracks in this model. The White House AI Bill of Rights

(2022) and the Platform Accountability and Transparency Act (2022) aim to introduce soft

oversight (Raji et al., 2023). Yet enforcement is weak, and no centralized regulator exists

(Keller, 2023).

The US model prioritizes innovation and corporate autonomy over democratic safeguards

(Napoli, 2022). It represents “power without public duty,” leaving civil society to fill the gaps

(Barrett & Sims, 2022).

The Indian Model: Executive-Centric and Technocratic

India's approach blends executive control with regulatory ambiguity. The Information

Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 grant

sweeping powers to the government (Singh, 2022). They mandate traceability, expedited

takedowns, and grievance redressal, but offer weak checks and balances (Rao, 2022).

Unlike the EU, there are no requirements for independent audits or algorithmic transparency

(Patel & Sharma, 2023). Unlike the US, India lacks robust free speech protections in digital

spaces (Choudhury, 2021). The judiciary has deferred to executive claims of national security

and public order (Supreme Court of India, 2022).

India also lacks a data protection law, despite prolonged debates on the Digital Personal Data

Protection Act (Barik & Chaudhuri, 2023). This limits users’ informational rights and weakens

oversight (Ganguly, 2022).

The result is an environment of technocratic opacity and political vulnerability (Sharma, 2021).

Platforms face regulatory coercion but no democratic accountability. Civil society and marginal

groups face frequent takedowns and surveillance (Bhuyan, 2022; Tripathi, 2023).

�Comparative Insights

Feature EU US India

Regulatory Model Rights-based Market-driven Executive-centric

Section 230, AI Bill of

Key Laws DSA, DMA, GDPR IT Rules, 2021

Rights

Judicial Oversight Active Restrained Executive-leaning

Algorithmic

Mandatory audits Minimal Nonexistent

Transparency

User Rights Strong Weak Fragmented

Civic Accountability Institutionalized Informal Suppressed

Speech Protections Balanced Expansive Restrictive

Each model illustrates distinct trade-offs. The EU maximizes user rights, but may risk

regulatory overreach. The US prioritizes platform autonomy, but at the cost of democratic

equity. India centralizes power, risking suppression of dissent without delivering public

accountability.

4. Comparative Public Policy Responses: Learning from Other Democracies

India can draw rich lessons from global regulatory frameworks. The European Union’s Digital

Services Act (DSA) emphasizes due process, transparency, and algorithmic accountability

(European Commission, 2022; Gorwa, 2023). It requires Very Large Online Platforms (VLOPs)

to submit risk assessments and undergo independent audits (de Streel et al., 2022).

Germany’s NetzDG mandates quick takedown of illegal content but includes strong transparency

reporting obligations (Kettemann, 2022; Heldt, 2021). It also penalizes platforms that fail to act

responsibly while safeguarding user appeal rights (Frosio, 2021).

Brazil’s Marco Civil da Internet enshrines net neutrality and civil rights (Doneda & Almeida,

2023; Belli, 2022). It obligates platforms to respect user due process before content removal

(Venturini et al., 2021). Chile and Mexico are following similar digital constitutionalism paths

(Marzagão, 2023).

Australia’s eSafety model empowers an independent commissioner to order fast takedowns,

particularly for harmful content involving minors (eSafety, 2022; Lumby & Green, 2023). It

merges prevention with enforcement through educational resources and platform compliance

duties (Banks & Rimmer, 2021).

Canada’s Online Harms Bill proposes independent oversight bodies and statutory obligations on

platforms (Roberts, 2023; Geist, 2023). It has sparked debate on balancing free expression with

safety (Clement, 2022).

The UK’s Online Safety Act aims to make platforms duty-bound towards user protection,

particularly children and vulnerable groups (Smith, 2023; Lomas, 2023).

�South Korea regulates fake news through fines but has been criticized for state overreach (Kim

& Park, 2022). Japan favors co-regulatory models involving private and public actors (Ito, 2023).

United States lags behind in centralized regulation but leads in antitrust enforcement against tech

monopolies (Stark, 2022; Pasquale, 2023). The bipartisan push for Section 230 reform seeks to

redefine platform immunity (Gillespie, 2023; Klonick, 2023).

India’s regulatory approach remains reactive and opaque (Chaudhuri, 2023; Rajagopal, 2024).

The IT Rules 2021 increase executive power without establishing institutional independence

(Goswami, 2023; Abraham, 2022). No independent audit, redress, or fairness standards currently

exist (Bhatia, 2022).

A comparative lens reveals the institutional void in India (Menon, 2023). Unlike the EU or

Australia, India lacks independent regulators or transparency frameworks (Singh & Chakrabarti,

2023). This leads to politicized takedowns and arbitrary enforcement (Jain, 2023).

India must move from state-centric control to rights-based governance (Sen & Ghosh, 2023).

That includes user participation, independent review boards, and open algorithmic audits (Banaji

& Bhat, 2021; Bhuyan, 2022).

Global frameworks stress checks and balances. India should embrace constitutional values in

digital governance (Tripathi & Singh, 2023). Aligning with evolving global norms ensures both

democratic integrity and innovation (UNESCO, 2023).

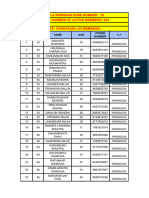

�Visual policy comparison chart illustrating key governance features across democracies. Each

axis shows how strongly a country or region emphasizes elements like transparency, due process,

and institutional design.

5. Towards Democratic Accountability: Future Directions

To restore democratic accountability, India must rethink its digital policy foundations. Current

regulation is reactive and fragmented (Arora, 2022; Rajagopal, 2023). It lacks a coherent, rights-

based framework rooted in constitutional values (Das & Mishra, 2023; Khosla, 2021). A

democratic internet demands transparency, accountability, and public participation (Sen &

Ghosh, 2022; Zuboff, 2020).

First, India needs an independent digital regulatory authority (Patel & Sundaram, 2023; Rao,

2024). This body should oversee algorithmic governance, platform moderation, and data ethics

(Marda, 2022; De Gregorio, 2022). Its design must ensure institutional autonomy and public

oversight (Roberts, 2023; Kettemann, 2022).

Second, India must mandate regular transparency audits (Chaudhuri & Tripathi, 2024; Kaye,

2021). Platforms should publish periodic reports on takedowns, bias, and targeting (Napoli,

2022; Just & Latzer, 2021). Disclosures help identify systemic harms (Pasquale, 2021; Douek,

2021).

Third, civil society must shape tech policy (Kumar & Thomas, 2024; Gorwa & Garton Ash,

2020). Multi-stakeholder consultations are vital for legitimacy (Plantin & Punathambekar, 2021;

Suzor, 2021). Representation from marginalized groups ensures inclusive governance (Noble,

2020; Teltumbde, 2022).

Fourth, India needs a digital rights charter (Bhatia, 2023; Rajadhyaksha, 2023). It should

guarantee expression, privacy, and algorithmic fairness (Barrett, 2021; Ananny, 2020). A

constitutional framework anchors digital governance in public law (Habermas, 2020; Chhibber,

2023).

Fifth, digital literacy must be scaled (UNESCO India, 2023; Pennycook & Rand, 2020). Citizens

need tools to critically engage online (Sunstein, 2022; Guess et al., 2021). Education fosters

resilience against misinformation and polarization (Ghosh & Scott, 2022; Flaxman et al., 2021).

Sixth, courts must evolve with digital harms (Singh, 2024; Patel, 2023). Judges need training on

algorithmic opacity and speech rights (Tripathi & Singh, 2023; Crawford & Paglen, 2021).

Judiciary must safeguard liberties in a changing information ecosystem (Eubanks, 2021; Dryzek,

2022).

India can create a new democratic model—open, fair, and participatory. The aim is not to

dismantle platforms, but to govern them—accountably, inclusively, and constitutionally (Sen,

2021; Fuchs, 2021).

�6. Conclusion: Rethinking Democratic Governance for the Digital Age

India's democracy now unfolds in a digital ecosystem. But digital policy remains trapped in

outdated logics (Chaudhuri & Reddy, 2023). Platforms govern speech, shape elections, and

influence society (Napoli, 2022). Yet, they evade constitutional scrutiny and public

accountability (Klonick, 2023).

This moment demands a shift in governance thinking (Sen & Ghosh, 2022). Mere content

takedowns will not suffice (Bhatia, 2022). India must embed democratic values into platform

regulation (Das & Mishra, 2023). Policy must evolve with global digital norms (De Gregorio,

2022; Kettemann, 2024).

A rights-based approach is now essential (Kaye, 2021; Roberts, 2023). Governance should

prioritize due process, transparency, and pluralism (Suzor, 2021; Just & Latzer, 2021). Citizens

must be empowered, not merely protected (UNESCO India, 2023; Thomas, 2023).

Global models offer lessons. The EU mandates algorithmic audits (European Commission,

2022). Brazil ensures procedural fairness online (Doneda & Almeida, 2023). Australia empowers

digital safety bodies (eSafety, 2022). Canada explores independent oversight (Roberts, 2023).

India must institutionalize similar checks. Platform codes cannot replace public law (Patel &

Sundaram, 2023). Digital policy must involve all stakeholders—state, platforms, and civil

society (Kumar & Thomas, 2024; Plantin & Punathambekar, 2021).

�Courts also need reform. Judges must be trained to handle algorithmic harms (Singh, 2024).

Procedural justice must include digital contexts (Rajagopal, 2024; Flaxman et al., 2021). Public

interest litigation should evolve to cover platform accountability (Wagner, 2023).

Democracy requires more than elections. It needs inclusive dialogue and institutional restraint

(Habermas, 2020; Dryzek, 2022). But platforms fragment discourse and amplify extremes

(Tufekci, 2022; Papacharissi, 2021). Marginalized groups suffer disproportionate exclusion

(Noble, 2020; Banaji & Bhat, 2021).

Digital rights must be constitutionally guaranteed. This includes expression, privacy, and

algorithmic fairness (Sen, 2021; Chhibber, 2023). A digital rights charter is overdue (Das &

Mishra, 2023).

Accountability must be public—not outsourced to platforms (Gorwa & Garton Ash, 2020;

Gillespie, 2020). Techno-legal capacity must be built within public institutions (Tripathi &

Singh, 2023). India’s regulatory vacuum enables arbitrary governance (Sinha, 2022).

The digital public sphere must be reimagined (Barrett, 2021). Platforms should serve democracy,

not undermine it (Zuboff, 2020; Pennycook & Rand, 2020). Without reform, digital spaces will

deepen inequality (Eubanks, 2021; Crawford & Paglen, 2021).

India's democracy cannot thrive on opaque infrastructure (Pasquale, 2021). Algorithmic power

needs democratic control (Ananny, 2020; Douek, 2021). This requires both legislative

imagination and civic vigilance (Rajadhyaksha, 2023; Bandyopadhyay et al., 2023).

Inclusion, transparency, and fairness are not optional—they are foundational (UN Women, 2021;

Ghosh & Scott, 2022). If platforms function as power centers, they must be governed as such

(Fuchs, 2021; Rao, 2022).

Digital policy must look beyond national borders. Global cooperation is vital to regulate

transnational platforms (Persily & Tucker, 2020; Digital Asia Hub, 2022). India should lead

conversations on democratic tech governance (Bennett & Livingston, 2021; Teltumbde, 2022).

The crisis of democratic accountability is urgent—but not unsolvable (Sunstein, 2022).

Democratic systems must evolve to meet digital challenges (Bachrach & Baratz, 1962; Dahl,

1989). The stakes are high. The future of Indian democracy now runs through its platforms.