25

Journal of Pediatric Intensive Care 1 (2012) 2529

DOI 10.3233/PIC-2012-005

IOS Press

Nurse staffing levels on the NPICU

in the island of Malta

Victor Grech*, Maria Cassar and Sandra Distefano

Paediatric Department, Mater Dei Hospital, Malta

Abstract

Purpose. Nurse staffing levels in neonatal paediatric intensive care units (NPICU) are often inadequate. Malta is a small Island in

the centre of the Mediterranean (total population around 400,000) with a birth rate of just under 4000/annum, with one NPICU.

This study analysed nurse staffing levels for a 1 year period in order to ascertain whether said levels are adequate or not.

Methods. Daily ward occupancies were classified by level of dependency, and ideal nursing requirements were estimated using

internationally approved standards, on a daily basis, for the period 12 month period from 01/04/2008 to 31/03/2009. These were

compared with the actual daily morning nursing levels to estimate deficit/s.

Results. There were a total of 373 admissions to the unit resulting in a total of 5464 patient days (daily census at 0700 hrs) and 1471

free bed days (occupancy 78.8%). Occupancy varied between 8 and 23 patients (mean 15). Staffing levels ranged between 7 and 17

nurses (mean 11). The overall mean deficit was of 3.3 nurses, but this ranged from a maximum of 11 to a rare surplus of 7 nurses.

Conclusions. This study only focused on a daily morning snapshot where the nursing staff is at its peak number the nocturnal

deficit is naturally worse. Furthermore, experience levels vary due to short rotations through the unit of inexperienced midwifery

staff. Moreover, there are no staff designated as responsible for further education and training, extra staff for unpredictable high

dependency situations, to compensate for leave, sickness, maternity leave, study leave, staff training and attendance at meetings.

Clearly, the Maltese NPICU is overall understaffed.

Keywords: Hospital bed capacity/statistics & numerical data, humans, infant, newborn, intensive care units, neonatal/manpower/

*statistics & numerical data, personnel staffing and scheduling/statistics & numerical data, workload/statistics & numerical

data

Introduction

The best quality neonatal care possible is crucial for

the outcome of sick neonates as this minimises

morbidity and mortality [1]. A reduction in morbidity

will inevitably also reduce the long-term burden of care

on the state [2]. It has been shown that throughout

Europe, since the 1990s, with increasing utilization of

surfactant and antenatal steroid administration for anticipated premature deliveries (and higher survival rates of

such neonates), there has been an increased requirement

for neonatal intensive cot utilization. Such cots are

low-volume and high cost, and are required at a level

of 1.01.9 cots per 1000 population with an average

*Corresponding author: Victor Grech, Paediatric Dept., Mater Dei

Hospital, Malta. Tel.: +356 99495813, E-mail: victor.e.grech@gov.mt.

70% occupancy [1]. It has been estimated that 12

neonates per 100 live births require at least 1 hour of

intensive care [3].

It has been shown that for these neonates, the risk

adjusted mortality rises linearly with level of occupancy,

such that infants admitted to full units have 50% greater

odds of dying than those admitted to units which are

only half full [3]. It is clearly crucial that staff levels

are appropriate to the dependency of the neonates, that

is, to the recommended nurse to patient ratios depending

on the severity of the condition being treated, as will be

explained below [1]. For this reason, it is recommended

that neonatal units should be planned to have an average

occupancy of 70% [1]. Malta has strong links with

the United Kingdom, with almost all trainees visiting

the United Kingdon. Systems in place therefore are virtually identical to the British system. The staffing

2146-4618/12/$27.50 2012 IOS Press and the authors. All rights reserved

�26

V. Grech et al. / Nurse staffing levels on the NPICU in the island of Malta

recommendations that are used in this study (see below)

are those used in the UK. These recommendations

remain in use although they are based on studies performed in the early 1990s, and must therefore be

regarded as minimum standards [4,5].

The level of dependency is determined by the acuity

and severity of the neonates condition/s, and the

greater the acuity and severity, the greater the recommended nurse to patient ratio will be [1].

Neonates in intensive care situations should have 1:1

nursing, and critically ill neonates (e.g. severe pulmonary hypertension) should have 2 nurses in attendance [6].

High dependency and special care should have

nurse to baby ratios of at least 1:2 and 1:4 respectively

[1]. Inclusion criteria for the various categories are

shown in table 1.

Setting

The Maltese Neonatal Paediatric Intensive Care Unit

(NPICU formerly St. Lukes Hospital Special Care

Baby Unit) is the only unit serving the Maltese

Table 1

Inclusion criteria for babies on the neonatal paediatric intensive care

unit

Intensive Care

Intubated and 1st 24 hours extubated.

NCPAP (nasal continuous positive airway pressure) at all and

<5 days old.

NCPAP at all and <1000g and for 24 hours after removal.

<29 weeks of gestation and <48 hours old.

Requiring major emergency surgery preoperatively and 24 hrs

postoperatively.

Complex procedures: Full exchange procedures, peritoneal

dialysis, infusion of inotrope or pulmonary vasodilator or

prostaglandin and for 24 hours after.

On day of death.

Other very unstable situations.

High Dependency

NCPAP and not filling any of the above criteria for

intensive care.

<1000g and not filling any of the above criteria for

intensive care.

Parenteral nutrition.

Fits.

Oxygen therapy and < 1500g.

Neonatal abstinence syndrome.

Complex procedures not as above: Partial exchange, arterial

line, chest drain, tracheostomy.

Severe apnoeas requiring recurrent stimulation.

Special Care

Any other condition not reasonably expected to be looked after

at home.

Archipelago, with a total catchment area of approximately 400,000 population and a live birth rate of just

under 4000 per annum [7]. The NPICU is a Level 3

Unit providing the whole range of medical neonatal

care. A Level 3 unit provides the whole range of medical neonatal care but not necessarily all specialist services such as neonatal surgery. Continuing neonatal

intensive care is also provided and is staffed by consultants whose principal duties are to the unit. There is 24hour resident cover by Higher Specialist Trainee in

paediatrics who has worked a minimum of four months

in neonatology. This doctor is available for the unit at

all times and is not required to cover any other service.

Two of the authors work on the unit, one as the

Nursing Officer in charge of the unit and the other as

the paediatric cardiologist for the country.

The unit officially has a total maximum capacity of 19

patients but this figure is not absolute in that since there

are no other units in the country, the unit stretches to

accommodate whatever number of admissions are

needed. The medical staff consists of three consultants

and two resident specialists, assisted by two basic specialist trainees. The on-call medical staff consists of a consultant covering the unit with two resident specialists on-site.

The nursing staff works on a 12 hour shift starting

and ending at 0700 hours and 1900 hours respectively

(day, night, rest and off) and each shift comprises 7 to

8 individuals. In addition, there are 4 to 5 nurses who

work daytime hours, i.e. up to 1600 to 1900 hours.

These figures do not include 2 unit nurses who manage the ward and also help out with general nursing

care if the need arises. In our unit, vacation leave is

only allowed for 1 member of rota staff and 1 member

of day staff.

During the period under study, the nursing staff

consisted of 39 full-time equivalents, with 45 individual nurses in total. There are a total of four shifts

with no nominated educators.

For the purposes of patient safety, these nurses or

midwives work completely supervised for the first

3 months of their rotation. Staff who work unsupervised

therefore have a minimum of 3 months of experience.

The level of individual experience varies from years to

decades.

The case mix is similar, year by year, and for the last

available year, admissions by gestational age were as

follows: 3 under 25 weeks of gestation, 14 between 25

and 27 weeks, 38 between 31 and 33 weeks, 64 between

34 and 36 weeks. There were also a total of 136 term

admissions and 44 paediatric admissions. Parent education is ad hoc and done by unit nurses.

�V. Grech et al. / Nurse staffing levels on the NPICU in the island of Malta

This study analyses admission data to the Maltese

NPICU for the period 01/04/200831/03/2009, and

compares unit patient occupancy with nurse staffing

levels on a daily basis. This was done in order to estimate daily deficits (if any) of nurse staffing levels in

relation to daily patient occupancy, after stratifying

patients to level of acuity in order to determine the individual level of ideal nurse to patient ratio, and total ideal

number of nurses that would have been needed on each

and every day. This was compared with the actual number of staff present, on each day, in order to identify days

where any staff deficits were definitely present.

Methods

Daily ward occupancies were compiled in an Excel

spreadsheet, and patients were classified as per table 1

as per recommended guidelines, [1] by the Nursing Officer in charge of the unit, on a daily basis, as a morning

snapshot. Morning nursing levels were also documented.

The data was entered into Excel by the ward clerk, on a

daily basis, and entry was checked by both authors.

Ideal daily nursing requirements were estimated

based on the above daily number of patients and their

dependency as per guidelines by diagnosis (table 1) [1]

i.e. patients requiring critical care should have 2 staff

in attendance, patients requiring intensive care should

require 1:1 nursing, patients requiring high dependency

and special care should have nurse to baby ratios of at

least 1:2 and 1:4 respectively [1]. The daily morning

nursing excess/deficit could therefore be calculated by

subtracting the desired number of nurses from the actual

number of nurses present as per above calculation.

The most severe condition requiring the greatest

level of dependency was utilized in patients with multiple diagnoses.

Official hospital admission and occupancy statistics

for NPICU for the period under study were also obtained.

Ethical approval was not sought as no patients/parents

were contacted and data was anonymised.

Results

There were a total of 373 admissions to the unit for

the period 01/04/200831/03/2009. These produced a

total of 5464 patient days (daily census at 0700 hrs).

Cot days by diagnosis are shown in table 2. Based on

an official estimate of a total maximum unit capacity

of 19 patients, there were 1471 free bed days with a total

27

bed occupancy of 78.8%. The average length of stay

was 14.6 days. There were a total of 38 non-neonatal

patients, with an age up to 3 years.

Summary statistics are given in table 3. Unit occupancy varied widely, and never fell below 8 patients,

and the maximum occupancy was 23 (mean 15). Staffing levels were equally variable, ranging between

7 and 17 nurses (mean 11). The overall mean deficit

was of 3.3 nurses, but this ranged from a maximum

of 11 to a surplus of 7 nurses. The deficits were unrelated to weekends, holiday periods or season.

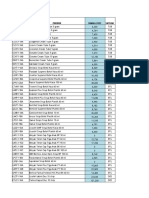

The trend in nursing deficit (and occasional surplus)

is depicted as a histogram in (Fig. 1). Values above the

baseline are nursing staff deficits, while values below

the baseline are nursing staff surpluses.

Discussion

Our study calculates desired daily staffing levels by

assigning individual daily patient dependency according

to the individual patient diagnosis, using published

Table 2

Cot days by diagnosis using table 1

Intensive Care

Intubated and 1st 24 hours extubated.

NCPAP (nasal continuous positive airway pressure)

at all and <5 days old.

NCPAP at all and <1000g and for 24 hours after

removal.

<29 weeks of gestation and <48 hours old.

Requiring major emergency surgery preoperatively and

24 hrs postoperatively.

Complex procedures: Full exchange procedures,

peritoneal dialysis, infusion of inotrope or

pulmonary vasodilator or prostaglandin and for 24

hours after.

On day of death.

Other very unstable situations.

High Dependency

NCPAP and not filling any of the above criteria for

intensive care.

<1000g and not filling any of the above criteria for

intensive care.

Parenteral nutrition.

Fits.

Oxygen therapy and < 1500g.

Neonatal abstinence syndrome.

Complex procedures not as above: Partial exchange,

arterial line, chest drain, tracheostomy.

Severe apnoeas requiring recurrent stimulation.

Special Care

Any other condition not reasonably expected to be

looked after at home.

Total

564

900

14

19

85

68

2

2806

0

0

0

4

28

208

12

0

536

5464

�28

V. Grech et al. / Nurse staffing levels on the NPICU in the island of Malta

Table 3

Summary statistics for unit occupancy, staffing levels, and staffing deficit for the entire period under study: 01/04/200831/03/2009

Mean

Standard Error

Median

Mode

Standard Deviation

Sample Variance

Minimum

Maximum

Unit occupancy

Nursing staff

Nursing deficit

15

0.14

15

17

2.6

7.0

8

23

11

0.09

11

11

1.7

3.0

7

17

3.3

0.17

4

4

3.2

10.4

7

11

recommendations, [1] and comparing the total derived

daily ideal nursing complement with the actual nursing

complement on that same day. This study shows an

overall deficit in the ideal level of staffing, except for a

few weeks toward the end of the study wherein the

admission rate temporarily fell.

Our study is limited by the fact that it only takes into

account one single unit, that is, the only such unit available in the country. This paper also focused on a daily

morning snapshot where the nursing staff is at its peak

number, and it is clear that the nocturnal deficit is therefore worse due to the absence of additional day only

staff. Indeed, the night shift consists, on average, of

78 nursing staff. This study also could not take into

consideration nursing experience levels as the staffing

is usually a mixture of variably experienced nurses and

midwives. For example, for the first 6 months of this

study (up to November 2008), a group of 6 midwives

were completing a 1 year rotation in NPICU. The subsequent rotation comprised 5 midwives, only 2 of which

were assigned to NPICU for a year, while the other

3 were only assigned for 6 months. For the purposes

of patient safety, these midwives work completely

supervised for the first 3 months of their rotation, hence

their addition to the dataset as full members of staff

is misleading. This rotation includes obstetric and

gynaecology wards, antenatal clinics, antenatal ultrasound and labour ward, hence little experience or preparation is gained preparatory to a tour of work on

NPICU.

In addition, the following paramedical staff does not

exist in our unit but is also recommended: a designated

nurse responsible for further education and training,

extra staff for unpredictable situations, e.g. one nurse

11

9

7

3

1

01

/0

4

15 /08

/0

4

29 /08

/0

4

13 /08

/0

5

27 /08

/0

5

10 /08

/0

6

24 /08

/0

6

08 /08

/0

7

22 /08

/0

7

06 /08

/0

8

19 /08

/0

8

02 /08

/0

9

16 /08

/0

9

30 /08

/0

9

14 /08

/1

0

28 /08

/1

0

11 /08

/1

1

25 /08

/1

1

09 /08

/1

2

23 /08

/1

2

06 /08

/0

1

20 /09

/0

1

03 /09

/0

2

17 /09

/0

2

03 /09

/0

3

17 /09

/0

3

31 /09

/0

3/

09

Deficit

3

5

7

Date

Fig. 1. Nursing staff deficit over the period 01/04/2008-31/03/2009.

�V. Grech et al. / Nurse staffing levels on the NPICU in the island of Malta

available on each shift for intensive or high dependency

cover, and extra staff to compensate for leave, sickness,

maternity leave, study leave, staff training and attendance at meetings [1]. This recommendation does not

include administration and secretarial cover.

Nursing deficits are common worldwide, and such

deficits, in themselves, may contribute to burnout,

reduced quality of care and carers actually opting out of

their profession [8]. Indeed, quality of care may deteriorate to levels such that unmet nursing care needs directly

lead to adverse events, up to and including death [9].

A nursing deficit is not uncommon in neonatal units,

and in the UK, it has been estimated that 79% of neonatal intensive care units have such deficits [1012].

One may speculate that this may be due not only to a

general lack of nursing cover, but also to the stress that

these jobs engender in staff, making them unpalatable

to employees in the long term. It has also been suggested that the increasing pressure to reduce the working hours all medical and paramedical staff and the

increasing duration of neonatal nurse training inevitably makes it more difficult for units to maintain staff

skills and to prioritise training [12,13].

It has been unequivocally shown that risk-adjusted

mortality in very low birthweight or preterm infants is

associated with levels of nursing provision. For example, increasing the ratio of experienced nurses is associated with a decrease in risk-adjusted mortality [14].

Increasing the total ratio of nurse to patient has also been

shown to significantly reduce mortality on neonatal units

[14]. Indeed, staffing variations across units within the

same country (Canada) have also been shown to affect

outcome [15]. Staffing levels appear to be such a contentious issue that some researchers have also suggested

ways in which safer staffing of neonatal units may

achieved, including network-wide workforces, clinical

support workers and neonatal housekeepers [12].

Conclusion

As measured against the quoted recommended

staffing levels, the NPICU has often been understaffed during the period under study as measured

by the data and methods used, albeit the situation

29

appears to have temporarily improved toward the

study period. We hope that this analysis will prompt

the local Health Authorities to assign a higher priority

to staffing levels in our unit.

References

[1] British Association of Perinatal Medicine. Standards for hospitals providing neonatal intensive and high dependency care.

London: BAPM; 1996.

[2] Hack M. Consideration of the use of health status, functional

outcome, and quality-of-life to monitor neonatal intensive

care practice. Pediatrics 1999; 103: 31928.

[3] International Neonatal Network, Scottish Neonatal Consultants, Nurses Collaborative Study Group. Risk adjusted and

population based studies of the outcome for high risk infants

in Scotland and Australia. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed

2000; 82: F11823.

[4] Williams S, Whelan A, Weindling AM, Cooke RWI. Nursing

requirements for neonatal intensive care. Arch Dis Child

1993; 68: 5348.

[5] Northern Neonatal Network. Measuring neonatal nursing

workload. Arch Dis Child 1993; 68: 53943.

[6] Standards for Paediatric Intensive Care. London: Paediatric

Intensive Care Society; 1996.

[7] National Statistics Office. National Statistics Office, Malta:

Demographic Review for the Maltese Islands (annual publication); 2008.

[8] Poghosyan L, Clarke SP, Finlayson M, Aiken LH. Nurse

burnout and quality of care: cross-national investigation in

six countries. Res Nurs Health 2010; 33: 28898.

[9] Lucero RJ, Lake ET, Aiken LH. Nursing care quality and

adverse events in US hospitals. J Clin Nurs 2010; 19: 218595.

[10] Tucker J, Tarnow-Mordi W, Gould C, Parry G, Marlow N.

UK neonatal intensive care services in 1996. On behalf of

the UK Neonatal Staffing Study Collaborative Group. Arch

Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 1999; 80: F2334.

[11] Tucker J. UK Neonatal Staffing Study Group. Patient volume,

staffing, and workload in relation to risk-adjusted outcomes in

a random stratified sample of UK neonatal intensive care

units: a prospective evaluation. Lancet 2002; 359: 99107.

[12] Watkin SL. Managing safe staffing. Semin Fetal Neonatal

Med 2005; 10: 918.

[13] Hamilton KE, Redshaw ME, Tarnow-Mordi W. Nurse staffing in relation to risk-adjusted mortality in neonatal care.

Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2007; 92: F99103.

[14] Callaghan LA, Cartwright DW, ORourke P, Davies MW.

Infant to staff ratios and risk of mortality in very low birthweight

infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2003; 88: F947.

[15] Lee SK, McMillan DD, Ohlsson A, Pendray M, Synnes A,

Whyte R, Chien LY, Sale J. Variations in practice and outcomes in the Canadian NICU network: 19961997. Pediatrics 2000; 106: 10709.