X bar syntax tree diagram exercises with answers

Syntax tree diagram exercises. Syntax tree diagram examples. Syntax tree diagram exercises with answers. How to make syntax tree diagram. X bar syntax tree diagram exercises with answers pdf.

Constituency tests and phrase structure rules provide a useful starting point for thinking about the structure of possible sentences, but they don’t really start explaining why certain structures are grammatical, or predicting what possible and impossible grammars might look like. In this section we introduce X-bar theory, which aims to make stronger

predictions by restricting the shape of possible trees. It’s called that because it introduces an extra layer of structure inside phrases called the “bar level”. To see why we might want to constrain what trees are possible, let’s begin by thinking about a type of structure that’s really easy to describe using a phrase structure rule: Weird phrase structure

rule: NP –> V (Adj) PP This rule is weird because it’s a noun phrase that’s missing the noun: we already saw in Section 6.3 is that what makes something a noun phrase is precisely that it has a noun inside it.

The restriction that all natural languages phrases have heads of the same category is the first limit we’ll put on possible structures in X-bar theory: Every phrase (XP) has a head of the same category (X) And this goes the other way as well: all heads (words) project (or “occur inside”) a phrase of their category: Every head (X) projects a phrase of the

same category (XP) What this means is that even when a noun or verb—or any other category—doesn’t obviously have any other words in the same phrase as it, it’s still inside an NP or a VP. In other words, while the two sentences in (1) are in one sense very different (one has two words, the other has 11), in another sense they have the same

structure: both sentences consist of an NP followed by a VP. (1) a. Cats sleep. b. The many very fast spaceships carried a lot of valuable cargo. By default, in X-bar theory we assume that the same constraints apply to all categories and phrases, and that they apply in all languages. In the absence of evidence to the contrary, we assume that determiners

occur inside determiner phrases (DPs), degree words occur inside degree phrases (DegPs), and so on. The assumption that all phrases involve the same structure, and that this is true in all languages, is a hypothesis. If we encounter evidence that is inconsistent with this hypothesis, we would revise the theory to account for new data.

Active research in syntax consists of investigating grammatical patterns in languages, and showing how they do (or do not) require specific revisions to current syntactic theories. The key feature of X-bar theory (and the source of its name) arises from the observation that phrases aren’t just a flat structure.

Our phrase structure rule for NPs, for example, could build NPs that contain a determiner (or DP), a noun, and a PP, but there was no sub-grouping. The tree diagram in Figure 6.5 shows this. (the triangle over robots indicates that we have abbreviated structure inside this constituent.) Figure 6.5 Tree diagram for [a picture of robots] What we find if

we look at phrases of all types, in many languages, is that head is always in a closer relationship with one other element inside the phrase, than with anything else. Specifically, heads are in a closer relationship with their complement—remember that in English the complement follows the head of the phrase, while it can come before the head in other

languages.

We saw in Section 6.3, for example, that verbs determine whether and how many objects they combine with. Above we saw that adjectives generally combine with PP complements, but that a few adjectives idiosyncratically allow NP complements. This means that there are units—constituents—inside phrases. So not only do all heads have phrases,

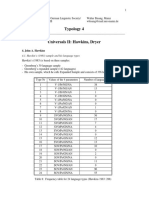

and all phrases have heads, but there is what we might call a “mid sized sub-phrase” in every phrase (or an “intermediate phrase”). This mid-sized phrase is called X-bar (written X’), which is where the theory gets its name. So we expand X-bar theory to the following generalizations, expressed in phrase structure rules: XP, YP, and ZP are all variables

over any category of phrase. These rules can be read as saying: Every phrase (XP) must have a bar-level of the same category (X’) within it, optionally preceded by another phrase (YP). Every bar-level (X’) must have a head of the same category within it, optionally followed by another phrase (ZP). The positions occupied by YP and ZP are argument

positions, and they have special names. The names for structural relations in trees are adapted from family relationships: parent, child, etc. Complement: Sibling of the head X (child of X’) is its complement Heads select their complement (including if they take a complement) Specifier: The child of XP, sister of X’ is the specifier of the phrase If we put

these labels in the tree in place os “YP” and “ZP” above, we get a general X-bar template for English (specific to English because it includes the linear order found in English). Figure 6.6 Generalized X-bar template (for English, head initial) What is the evidence for bar levels? In the remainder of this section we review the evidence for sub-constituents

inside NPs and VPs. Evidence for N’ The evidence for N’ (“N-bar”) involves showing that a noun is in a closer relationship with a PP that follows it than it is with a previous determiner. We can show this with constituency tests that target this sub-NP unit. These tests are a bit trickier to apply than the constituency tests covered in Section 6.4, but they

follow the same general principle. Here we will only go through one of these tests: one-replacement.

Just as a pronoun can replace a whole NP, the word “one” can (for at least some speakers of English) replace a noun and a following prepositional phrase, leaving behind anything before the noun. Like other kinds of replacement, especially replacement with do for VPs, one-replacement requires that there’s an earlier NP that “fills in” what’s being

replaced. (2) [NP Yesterday’s launch of a spaceship ] was exciting, but [ today’s one ] was not. (where [one]=[launch of a spaceship]) By contrast, you can’t replace a determiner and an N with one, leaving the PP behind: (3) *[NP The launch of a spaceship ] is exciting, but [ one of a mining drone ] is not. (where [one]=[the launch]) This gives us the

following overall structure of an NP, showing a closer relationship between the N and a following PP than between either of those and the preceding determiner or possessor. Figure 6.7 Tree diagram for [ yesterday’s launch of a spaceship ] Evidence for V’ We can do similar tests to find a constituent inside VP, consisting of the verb and its object.

For example, we can elide a verb and its object, leaving a previous AdvP behind, but we cannot elide AdvP + V, leaving the NP object behind. (4) a. They will [VP quickly build a spaceship], and we will [VP slowly _ ] b.

*They will [VP quickly build a spaceship], and we will [VP _ an orbital station ] (ungrammatical if what’s missing is [quickly build]) For many speakers the contrast is clearer with do so replacement: do so can replace a verb and its object, but can’t replace an adverb and verb if this strands the object. (5) a. They will [VP quickly build a spaceship], and

we will [VP slowly do so ] b. *They will [VP quickly build a spaceship], and we will [VP do so an orbital station ] (ungrammatical if what’s missing is [quickly build]) As with noun phrases, we can represent the fact that the verb and its object form a constituent, to the exclusion of any adverbs, by putting them both under the V’ node. Figure 6.8 Tree

diagram for [ quickly build a spaceship ] “Empty” bar levels As with the hypothesis that all heads project phrases, even when there are no other words in the phrase, X-bar theory assumes that all phrases contain at least one bar level, even when it is not needed to host a complement. So for the sentence in (6), we would have the tree in Figure 6.9,

where every phrase has a bar level even though none of the phrases we’ve drawn includes a complement: (6) The spaceships landed. Figure 6.9 Tree diagram for The spaceships landed. This tree also illustrates something that’s still missing from our implementation of X-bar theory: we’ve said that every phrase has to have a head, but our sentences

are currently headless.

In the next section we turn to the proposal that all sentences are projected from a tense head. Check your understanding Coming soon! Navigation If you are following the alternative path through the chapter that interleaves core concepts with tree structures, the previous section was 6.13 From constituency to tree diagrams and the next section

is 6.15 Trees: Sentences as TPs. Part Of: Language sequence Followup To: An Introduction to Generative Syntax Content Summary: 800 words, 8 min read Explaining Substitution Consider the sentence “I bought this big book of poems with the red cover”. In everyday language, we often replace words and phrases with indexing words like “one”. Call

this indexing replacement.The meaning of these words can be obtained from the context. At first glance, indexing replacement seems to target a branch in the syntax tree.

For example: I bought that big one of poems with the red cover (“one” replaces the noun) I bought one (“one” replaces the entire noun phrase) But there are several other substitutions don’t follow from branch replacement: I bought that big one. I bought that small one I bought that big one of poems with the blue cover Perhaps our notion of noun

phrases is too flat.

Perhaps we need additional nodes to describe structure within the noun phrase. We will call these intermediate nodes N’, (where N → N’ → N’’ = NP): This new tree successfully predicts all substitution phenomena, by modeling “one” as replacing various “N-bar” nodes: We can similarly introduce depth to our verb phrases (VPs), by using intermediate

V’ (“V-bar”) nodes: The X-Bar syntax tree provides a simple explanation of the “do so” substitution effects: I will do so in the office before the party. I will do so before the party. I will do so. A General Theory of Phrases We can revise our original NP and VP rules to reflect our intermediate N’ and V’ nodes: What if noun and verb phrases are

instantiations of a more general phrase structure? Just as group theory identifies overlap in the axioms of addition and subtraction, X-bar theory explores the similarity between NP and VP rules. There are only four kinds of phrase constituents: The head carries the central meaning of the phrase. Consider the sentence “The tall student who is

wearing the red shirt asked questions of her professor, after the lecture.” The central meaning is retained if we remove all non-head words: “student asked questions”. The specifier points to the head. For nouns, specifiers include determiners (“the”) and possessives (“her”). For verbs, adverbs occasionally fill this role (“quickly”). The complement

tends to feel intimately related to the head of a phrase (e.g., “of poems” in “a book of poems”). Adjuncts, on the other hand, tend to feel more optional (e.g., “big” in “big book”). Adjuncts vs Complement Given that adjuncts and complements both often inhabit prepositional phrases, it is perhaps surprising that they should behave differently. The

distinction between adjuncts and complements explains why this should be the case. Let us look at four behavioral differences: Difference #1. Adjuncts can be reordered freely. Consider our example verb phrase: This rule means that our two adjuncts can be shuffled, but the complement NP must retain its original position I will read the letter in the

office before the party (Original order: valid) I will read the letter before the party in the office (Adj reorder: valid) *I will read in the office before the party the letter (Compl reorder: invalid) Difference #2. Indexing replacement cannot strand the complement. For example, I will do so in the office before the party (Adj is stranded: valid) *I will do so

the letter before the party (Compl is stranded: invalid) Consider another part of speech we have not yet considered: conjunction words like “and” and “or”.

Difference #3. Conjunction words bind adjuncts together, and complements together. But adjunct-complement bindings are non-grammatical. Consider our example noun phrase: Three examples to illustrate how conjunction works: I bought the book of poems and of short stories.

(Compl-compl conjunction: valid) The book with the red cover and the black spine. (Adj-adj conjunction: valid) *The book of poems and with the red cover. (Compl-adj conjunction: invalid) What X-Bar Theory Tells Us About Memory Earlier, I introduced the distinction between episodic and semantic memory: Semantic: ability to remember facts and

concepts (e.g., hands have five fingers) Episodic: ability to remember events or episodes (e.g., dinner last Tuesday night) Concepts are learned by extracting commonalities from episodic memories. If you see enough metallic blocks moving around on four cylinders, you’ll eventually consolidate these objects into the CAR concept: In philosophy, I

suspect the concepts of necessity and contingency relate to semantic and episodic memory, respectively. In linguistics, I suspect complements help locate concepts in semantic memory, whereas adjuncts assist episodic localization. In the sentence “I bought the book of poems with the red cover”, the complement helps us activate the concept POEM-

BOOK, whereas the adjunct creates sense-predictions that locate it within our episodic memory. Takeaways With flat syntax trees, it is difficult to explain indexing substitution (e.g., “bought a book” → “bought one”) If we make syntax trees binary, by introducing intermediate X’ (“X-Bar”) nodes, substitution becomes more straightforward. Noun and

verb phrases thus parameterize a more general phrase structure. Phrases have four kinds of constituents: head, specifier, complement, and adjuncts. The differences between complements and adjuncts are instructive: Only adjuncts can be reordered. Indexing replacement cannot strand the complement. Conjunction cannot bind across categories In

human cognition, complements and adjuncts may correspond to semantic and episodic memory, respectively. Draw tree structures for the following sentences and answer the questions Go to another exercise on X-bar structures X-bar theory makes the simple proposal that every phrase in every sentence in every language is organized the same way.

Every phrase has a head, and each phrase might contain other phrases in the complement or specifier position. Check Yourself 1. In this tree diagram, what position does the DP my coffee occupy? Head. Specifier. Complement. 2. In this tree diagram, what position does the D my occupy? Head. Specifier. Complement. 3. In this tree diagram, what

position does the NP Hamilton occupy? Head. Specifier. Complement.

Video Script We’re starting to look at how our minds organize sentences. We’ll see that within each sentence, our mental grammar groups words together into phrases and phrases into sentences. We saw in the last unit how we can use tree diagrams to show these relationships between words, phrases and sentences. The theory of syntax that we’re

working within this class is called X-bar theory. X-bar theory makes the claim that every single phrase in every single sentence in the mental grammar of every single human language, has the same core organization. Here’s a tree diagram that shows us that basic organization. Let’s look at it more closely. According to x-bar theory, every phrase has a

head. The head is the terminal node of the phrase. It’s the node that has no daughters. Whatever category the head is determines the category of the phrase. So if the head is a Noun, then our phrase is a Noun Phrase, abbreviated NP. If the head is a verb (V) then the phrase is a verb phrase (VP). And likewise, if the head is a preposition (P), then the

phrase is a preposition phrase (PP), and Adjective Phrases (AP) have Adjectives as their heads. So the bottom-most level of this structure is called the head level, and the top level is called the phrase level. What about the middle level of the structure? Syntacticians love to give funny names to parts of the mental grammar, and this middle level of a

phrase structure is called the bar level; that’s where the theory gets its name: X-bar theory. So if every phrase in every sentence in every language has this structure, then it must be the case that every phrase has a head. But you’ll notice in this diagram that these other two pieces, the specifier and the complement, which we haven’t talked about yet,

are in parentheses. That’s to show that they’re optional — they might not necessarily be in every phrase. If they’re optional, that means that it should be possible to have a phrase that consists of just a single head — and if we observe some grammaticality judgments, we can think of phrases and even whole sentences that seem to contain a head and

nothing else. We could have a noun phrase that consists of a single noun — Coffee? or Spiderman! We could have verb phrase that has nothing in it but a verb, like Stop! or Run! Or an adjective phrase might consist of only a single adjective, like Nice… or Excellent! But X-bar theory proposes that phrases can have more in them than just ahead. A

phrase might optionally have another phrase inside it in a position that is sister to the head and daughter to the bar level. If there’s a phrase in that position, it’s called the complement.

The most common kinds of head-complement relationship we see are a verb taking an object or a preposition taking an object. Let’s look at some examples. Here we’ve got a verb phrase, with the verb drank as its head. That head has the noun phrase coffee as its sister. The NP coffee is sister to the verb head and daughter of the V-bar node so it is a

complement of the verb. Here’s another example that has the same structure, but a different category.

The head of this phrase is the preposition near, so the phrase is a preposition phrase. The complement of the preposition is the noun phrase campus and the whole phrase is near campus. Try to think of some other examples of verbs and prepositions that take noun phrases as their complements.

�The other common place we see a head-complement relationship is between a determiner and a noun.

In phrases like my sister, those shoes, and the weather, the determiner is a head that takes an NP complement. X-bar theory also proposes that phrase can have a specifier. A specifier is a phrase that is sister to the bar-level and daughter to the phrase level. The most common job for specifiers is as the subjects of sentences, so we’ll look at those in

another unit.