Arch Womens Ment Health (2012) 15:139–143

DOI 10.1007/s00737-012-0264-4

SHORT COMMUNICATION

Mindful pregnancy and childbirth: effects of a mindfulness-

based intervention on women’s psychological distress

and well-being in the perinatal period

Cassandra Dunn & Emma Hanieh & Rachel Roberts &

Rosalind Powrie

Received: 16 June 2011 / Accepted: 14 February 2012 / Published online: 1 March 2012

# Springer-Verlag 2012

Abstract This pilot study explored the effects of an 8-week Astin 2008). Recurring themes emerging from qualitative

mindfulness-based cognitive therapy group on pregnant investigations into participants’ experience of the change

women. Participants reported a decline in measures of processes in mindfulness-based interventions include the

depression, stress and anxiety; with these improvements value of a shared group experience, living in the moment

continuing into the postnatal period. Increases in mind- and adopting an accepting attitude (Mason and Hargreave

fulness and self-compassion scores were also observed 2001).

over time. Themes identified from interviews describing The current pilot study aimed to further explore the

the experience of participants were: ‘stop and think’, effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on the psycho-

‘prior experience or expectations’, ‘embracing the present’, logical distress and well-being of pregnant women. It is

‘acceptance’ and ‘shared experience’. Childbirth prepara- important to note that mindfulness-based interventions do

tion classes might benefit from incorporating training in not target symptom reduction as a goal, but rather their

mindfulness. primary aim is to increase people’s ‘psychological flexi-

bility’. Psychological flexibility refers to an individual’s

Keywords Mindfulness . Pregnancy . Stress . Anxiety . capacity to make choices in accordance with their authentic

Depression . Intervention values, despite the symptoms they may be experiencing

(Hayes et al. 1999). Paradoxically, research continues to

demonstrate that often as a result of improved psycho-

Introduction logical flexibility there is a reduction in symptoms

(Hayes et al. 1999; William et al. 2007). Therefore, it

Preliminary evidence for the efficacy of mindfulness-based was hypothesised that women participating in an 8-week

interventions during pregnancy is emerging (Dimidjian and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) class

Goodman 2009; Duncan and Bardacke 2009; Vieten and would experience reduced stress, depression and anxiety

as well as increased mindfulness and self-compassion.

The use of semi-structured interviews to elicit personal

C. Dunn (*) : R. Roberts

accounts of participants’ experience of the group aimed

School of Psychology, University of Adelaide,

Adelaide, SA 5000, Australia to provide insight into the mechanisms by which change

e-mail: cassandradunn@optusnet.com.au occurred.

E. Hanieh

Discipline of Psychiatry, School of Medicine,

University of Adelaide, Methods

Adelaide, SA, Australia

Treatment group participants were outpatients receiving

R. Powrie

antenatal care at a large metropolitan Women’s and

Discipline of Paediatrics and Psychiatry, School of Medicine,

University of Adelaide, Children’s Hospital in Australia. They were between 12

Adelaide, SA, Australia and 28 weeks gestation at the commencement of the 8-week

�140 C. Dunn et al.

course. Exclusion criteria were (1) inability to attend at least class was facilitated by a consultant psychiatrist, along with

seven of the eight sessions and (2) current psychosis or active a counsellor, both of whom are accredited facilitators of the

substance abuse. At the commencement of the programme, MBCT programme.

there were 14 registered participants; however, three women The study was approved by the Ethics Committee, Child-

did not attend the first or any subsequent sessions. Of the 11 ren’s Youth and Women’s Health Services. All participants

women who did commence the 8-week programme, ten gave informed consent. The participants were asked to par-

consented to participate in the research. The mean age of ticipate in an interview with the author (CD), during which

the ten participants was 35.33 years (SD 04.53). Nine of they were asked to describe their experience of pregnancy,

the ten participants reported being in a committed relationship childbirth and life with a new baby, including any perceived

and five women had at least one other child. While the class benefits of the mindfulness skills they learned during the

was not promoted as a therapeutic intervention, nine out class. Interviews were recorded and transcripts were coded

of the ten participants reported a history of anxiety and/or using a thematic approach.

depression. At baseline, end of treatment and 6 weeks post-partum,

The control group participants were also pregnant the participants completed the depression, anxiety and

women receiving outpatient antenatal care at the Women’s stress scale (DASS21, Lovibond and Lovibond 1995),

and Children’s Hospital. The control group participants the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS, Cox

were between 17 and 29 weeks gestation when baseline et al. 1987), the Mindful Attention and Awareness Scale

measures were taken. At baseline, there were nine con- which measures the extent to which individuals are able to

trol participants. The mean age of the control group maintain awareness of present moment experience (Brown

participants was 27.67 years (SD 05.34). All women and Ryan 2003) and the Self-Compassion Scale (Neff

indicated they were in a relationship and one had another 2003) which assesses the ability to be kind and under-

child. No control group participants reported a history of standing towards oneself in instances of pain or failure,

anxiety or depression. rather than being harshly self-critical.

The eight-session programme undertaken by treatment

group participants was based on the MBCT programme first

developed by Segal et al. (2002). Modifications were made Results

to the mindful movement component of the programme to

ensure they were appropriate for pregnant women. Due to As the participant groups were small, reliable change

the group not being promoted as a treatment for mental indices were used to determine the number of partici-

illness, some sections of the programme that focused spe- pants in each group who experienced clinically reliable

cifically on depression were omitted from the programme. changes in scores from baseline to end of treatment and

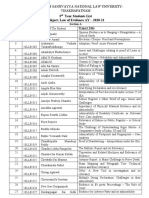

See Table 1 for a description of programme content. The from baseline to 6 weeks post-partum (Table 2). Notably,

three of four treatment group participants (75%) experienced a

clinically reliable decrease in stress symptoms from baseline

to post-treatment, with at least one participant reporting a

Table 1 Programme content of the Mindfulness-Based Cognitive

Therapy (MBCT) programme reliable change on the majority of measures. In contrast, there

was very little change in outcome scores within the control

Session Focus of session group.

number

Separate reliable change analyses were used to determine

1 Automatic pilot: committing to learning how to become the extent to which these changes were maintained over time

aware of each moment by comparing scores at baseline and at 6 weeks post-partum.

2 Dealing with barriers and introduction to the cognitive model Post-partum outcomes indicate that as many as 67% of the

3 Learning to take awareness intentionally to the breath treatment group participants experienced a positive change

4 Staying present, taking a wider perspective and relating in their levels of stress and self-compassion, and half the

differently to experience participants reported a positive change in their depression

5 Fostering an attitude of acceptance to see what if anything scores as measured by the EPDS.

needs to be changed All of the women interviewed reported that they con-

6 Relating to negative thoughts tinued to use the mindfulness skills either formally or

7 Managing warning signs, mastery and pleasurable activities informally, and this was the case regardless of if they had

8 Review and planning for regular mindfulness practice completed the full course. Most reported that they practised

This programme is described in detail in Segal et al. (2002) including

mindful breathing at the very least, and many reported still

detailed session agendas, activities and exercise, handouts for partic- using the CDs from the course to practise formal meditation

ipants and homework from time to time.

�Mindful pregnancy and childbirth 141

Table 2 Clinically reliable

changes on measures of Reliable improvement (based on RCI analysis)

psychological well-being from

baseline to end of treatment and Yes No Total Yes No Total

baseline to post-partum for

treatment and control group Baseline to end of treatment for treatment Treatment group (n04) Control group (n05)

participants Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) 1 3 4 0 5 5

DASS-21:

• Stress 3 1 4 0 5 5

• Anxiety 1 3 4 0 5 5

• Depression 0 4 4 1 4 5

Mindful Attention and Awareness Scale (MAAS) 1 3 4 0 5 5

Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) 0 4 4 0 5 5

Baseline to post-partum Treatment group (n06) Control group (n05)

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) 3 3 6 0 5 5

DASS:

• Stress 4 2 6 1 4 5

• Anxiety 2 4 6 1 4 5

• Depression 2 4 6 0 5 5

Mindful Attention and Awareness Scale (MAAS) 2 4 6 0 5 5

Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) 4 2 6 0 5 5

Five themes were identified that collectively describe the of how many sessions they attended. Participants’ subjective

experience of participants in the course; ‘stop and think’, accounts of their experience provide some insight into the

‘prior experience or expectations’, ‘embracing the present’, possible mechanisms by which mindfulness works to produce

‘acceptance’ and ‘shared experience’ (Table 3). improvements in psychological well-being. The overarching

themes identified in the current study are consistent with

those of earlier qualitative analyses; especially the idea of

Discussion acceptance, which is common to several recent qualitative

studies (e.g., Allen et al. 2009; Mason and Hargreaves

The results of this pilot study demonstrated that pregnant 2001). Other researchers have highlighted the value of having

women participating in a mindfulness-based group interven- a supportive group experience (Mason and Hargreaves 2001);

tion reported clinically reliable declines in depression, stress however, this is not an exclusive feature of a mindfulness-

and anxiety; with these improvements continuing into the based intervention. Future studies using an active control

postnatal period, changes not seen in the control group. group (for example, receiving social support or education),

Similarly, an increase in mindfulness and self-compassion matched in terms of history of mental health problems, would

scores were observed over time. These results provide help us to understand how much of the therapeutic benefit

tentative support for the findings of earlier pilot studies, experienced by our participants was due to the intervention, as

which found mindfulness training during the perinatal opposed to any change being due to the time and attention

period to produce reductions in negative affect and state received by group participants.

anxiety (Vieten and Astin 2008), reductions in pregnancy

anxiety and improvements in mindfulness (Duncan and

Bardacke 2009). Conclusion

Our limited quantitative results were supported by an

in-depth qualitative analysis that allowed for a rich un- While this study was limited by a small sample size and

derstanding of participant’s individual experience of the high attrition rate, it has yielded preliminary data supporting

group. Participants reported that stopping and breathing, the potential benefits of mindfulness in the perinatal period.

developing an attitude of acceptance, and coming into Future work with larger samples to provide a more robust

the present moment are all core aspects of mindfulness test of the effectiveness of MBCT programmes in pregnancy

that they have used to help them cope with pregnancy, and which further consider attrition is needed. However,

childbirth and parenting. Every participant spoke of the based on this and other recent pilot studies (Duncan and

benefits they experienced from learning these skills, regardless Bardacke 2009; Vieten and Astin 2008), we are able to

�142 C. Dunn et al.

Table 3 Themes and examples

Theme and description Examples

Stop and think

The words ‘stop and think’ were taken from a direct quote by ‘When I have the occasional bad day, I’m able to stop and not

one of the participants to describe a new way of responding let it get on top of me because of what I learned in the course.

to everyday stressors and relationship difficulties. The ability All those things we learned like just coming up with a list of

to notice thoughts, feelings and bodily sensations and consciously ways to feel good and being proactive. So that if you’re feeling

choose a response was described by all of the participants in bad, you don’t have to stay in the bad stuff, you can do something

various ways and describes an important skill they learned from even if it’s just to go out for a walk or have that bit of chocolate.’

the course. Specifically, participants referred to the act of noticing ‘When I get annoyed with them [family], I’ve learned to take a step

when feelings of frustration or anger arise and choosing not to act back and just breathe and think about what I’m going to say before

on those feelings but to instead ‘take a breath’ and choose a I open my mouth so that I don’t cause any dramas that don’t need

different response. to be caused.’

Prior experience or expectations

The theme of having a prior experience that increased one’s personal ‘I had a lot of reasons to want to continue in the course even though

interest in participating in (and persevering with) the course may sometimes I thought it was a bit radical and they were trying to get

provide insight into the factors that mediate participants’ positive us to do these crazy techniques… I needed to do this not just for

outcomes. A common experience described by many of the me, but for my family.’

participants was one of having experienced emotional difficulties ‘I just wish I’d got all this help that I needed before the first one

in the past and wanting this pregnancy and birth to be a new, [when she experienced post natal depression], you know?

different, and more positive experience. Things could have been so much different. I didn’t enjoy it then

and I sort of pushed him away and… I just wish I’d enjoyed him

as much as a baby as much as I have these two.’

Embracing the present

Being fully connected to the present moment is one of the core ‘It sounds sort of obvious, but keeping myself focused on the present

concepts of mindfulness practice, and so it is perhaps not especially in my interactions with the kids, just not being distracted.

surprising that this theme emerged particularly strongly from I’m sure it has benefits for my well-being and keeping me calm and

the data. Participants described various ways in which present more focused and less stressed.’

moment awareness has become an important everyday practice ‘If you’ve had a bad morning, being able to go ‘well that was a bad

morning but right now, everything’s fine. Right in this moment,

I’m well, the kids are fine, everything’s ok’ whereas before if I’d

had a bad morning I would have kept thinking all day about the

bad morning and thinking it’s never going to end or I’ll always be

yelling at the kids or whatever.’

Acceptance

The idea of acceptance or ‘surrender’ describes participants’ ‘He was a baby who screamed most of the time… I think I clung to

reports that they feel more able to let go of the struggle with what I missed about what life was like before. Just being able to do

how they would like things to be and accept things as they are. something by yourself or read a book or put him down. Putting him

down doesn’t happen very often… I’ve just had to surrender to that and

that’s the nature of how life is going to be and try to enjoy it for what it is.’

‘Sometimes I suffer from intrusive thoughts like scary thoughts like

what if I wanted to hurt him or something and if I experience those

thoughts now, I just think of them… well as nothing really. They’re

just thoughts. And I’ve been able to detach the emotional ‘Oh my god,

how could I even think that?’ response and because I’ve been able to

detach myself and because there is no emotional response I just don’t

really focus on it and so I don’t get those thoughts at all anymore… I’m

not kidding. That has really changed my life.’

Shared experience

All of the women reported that they greatly valued participating ‘It was good to meet other people and know you weren’t the only

in the group and forming relationships with the other participants. person. Doing group discussions, it was good to know you were

Sharing stories with the group had the benefit of normalising in a place where you felt comfortable to talk about it.’

people’s own experience.

conclude that women who learn mindfulness during psychological well-being. Teaching mindfulness in the

pregnancy are likely to use those skills to manage stressful perinatal period seems to have the effect of broadening

aspects of pregnancy, childbirth and parenting, resulting in women’s personal repertoire of coping strategies, and

reductions in psychological distress and improvements in this has potential to improve the developmental

�Mindful pregnancy and childbirth 143

trajectory of parents and infants. Pregnancy is a brief Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R (1987) Detection of postnatal

depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal

time in a woman’s life when she is open to receiving

Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 150:782–786

new information and skills to cope with birth and Dimidjian S, Goodman S (2009) Nonpharmacologic intervention and

parenting. With this in mind, existing childbirth prepa- prevention strategies for depression during pregnancy and the

ration classes might expand to incorporate some train- postpartum. Clin Obstet Gynecol 54:498–515. doi:10.1097/

GRF.0b013e3181b52da6

ing in mindfulness in order to reach participants who

Duncan LG, Bardacke N (2009) Mindfulness-based childbirth and

would otherwise not have the opportunity to learn parenting education: promoting family mindfulness during the

these important skills. perinatal period. J Child Fam Stud. doi:10.1007/s10826-009-

9313-7

Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KD (1999) Acceptance and com-

mitment therapy: an experiential approach to behavior change.

Guilford, New York

Conflicts of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH (1995) Manual for the depression anxiety

of interest. stress scales, 2nd edn. Psychology Foundation of Australia, Sydney

Mason O, Hargreaves I (2001) A qualitative study of mindfulness-based

cognitive therapy for depression. Br J Med Psychol 74:197–212

Neff K (2003) The development and validation of a scale to measure

References self-compassion. Self Identity 2:223–250

Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD (2002) Mindfulness-based

cognitive therapy for depression: a new approach to preventing

Allen M, Bromley A, Kuyken W, Sonnenberg SJ (2009) Participants’ relapse. Guilford, New York

experiences of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: “it changed Vieten C, Astin J (2008) Effects of a mindfulness-based intervention

me in just about every way possible”. Behav Cogn Psychother during pregnancy on post-natal stress and mood: results of a pilot

37:413–430 study. Arch Womens Ment Health 11:67–74

Brown KW, Ryan RM (2003) The benefits of being present: William M, Teasdale J, Segal Z, Kabat-Zinn J (2007) The mindful way

mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers through depression: freeing yourself from chronic unhappiness.

Soc Psychol 84:822–848 Guilford, New York

�Copyright of Archives of Women's Mental Health is the property of Springer Science & Business Media B.V.

and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright

holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.