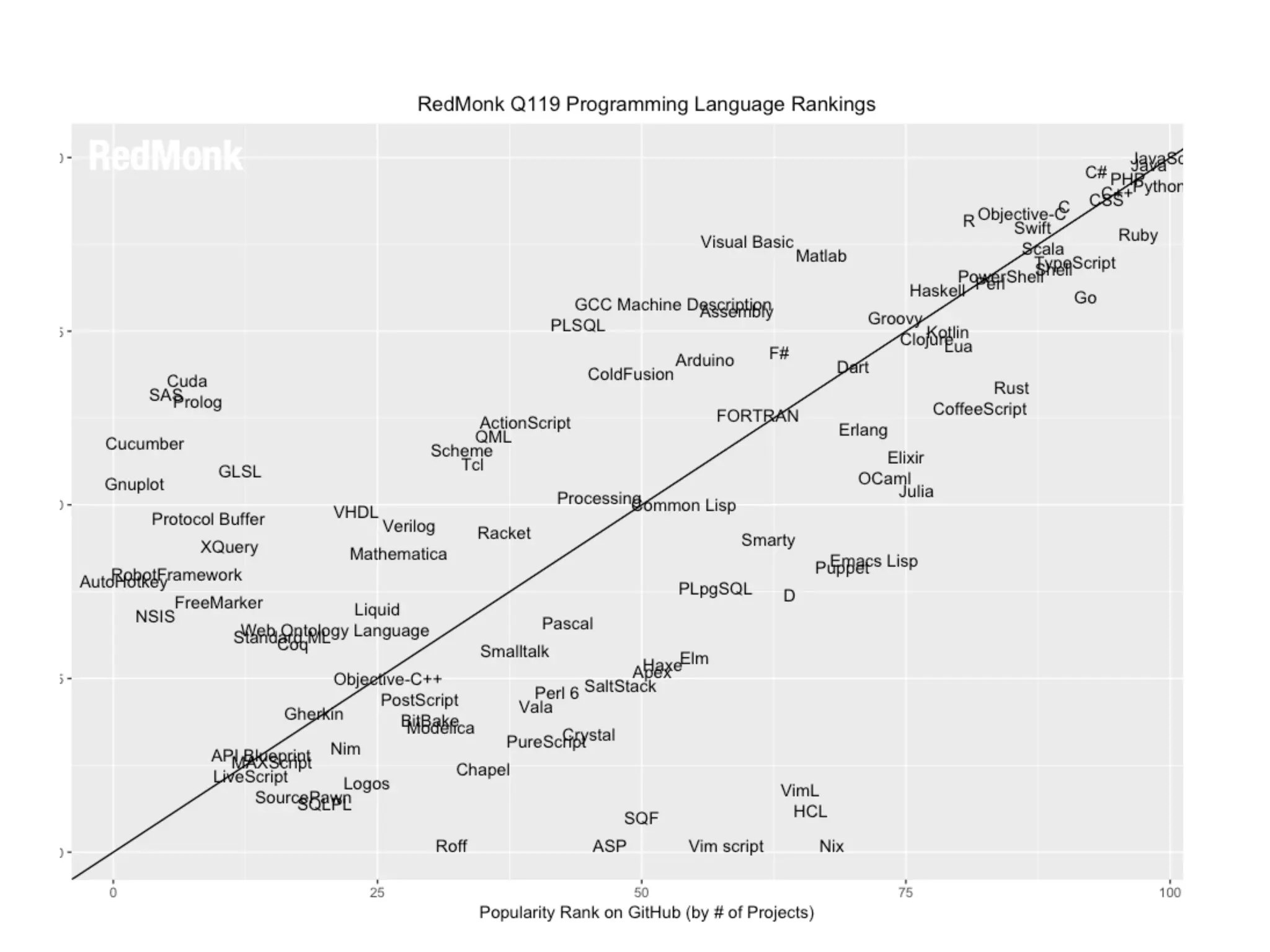

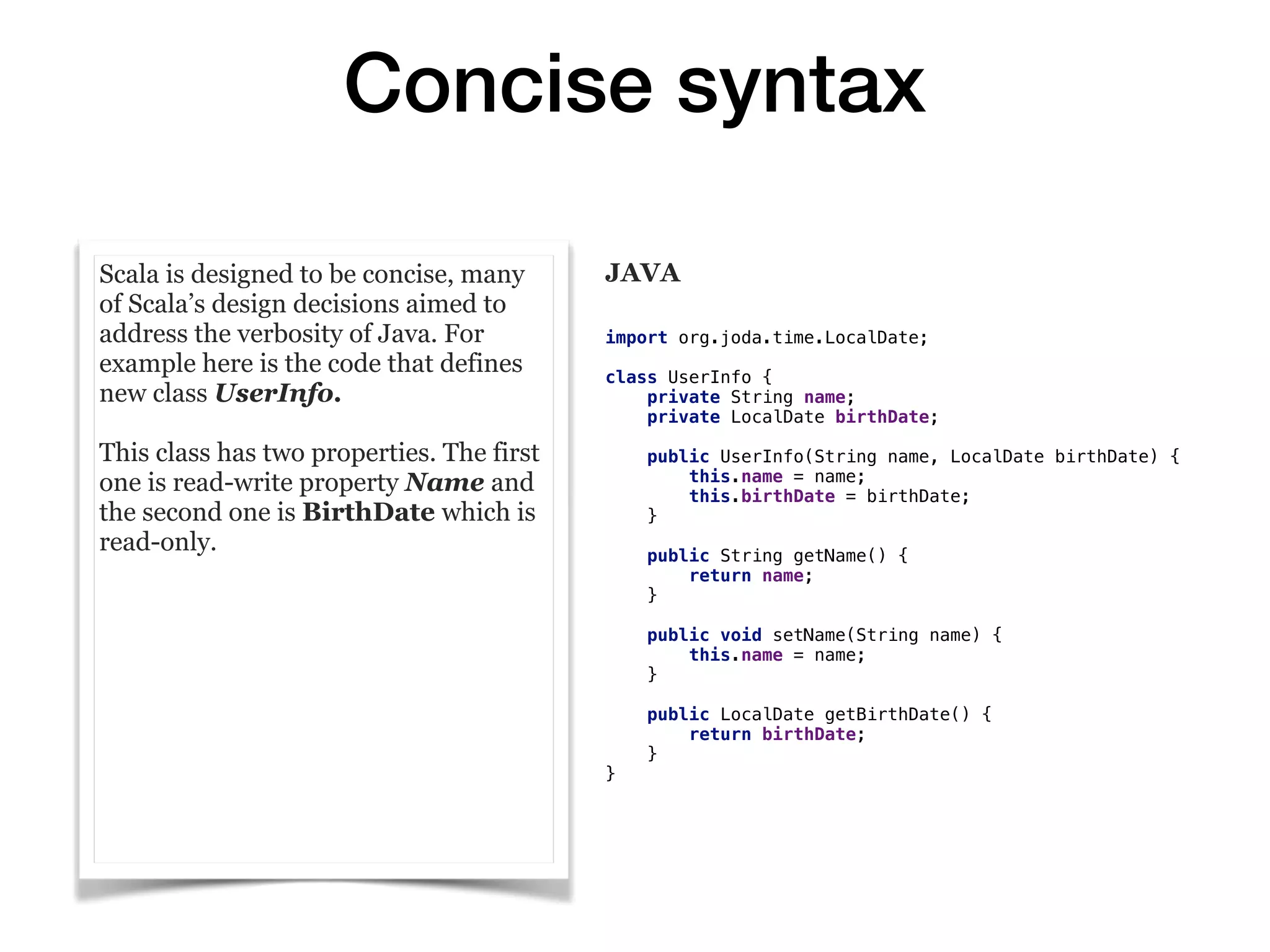

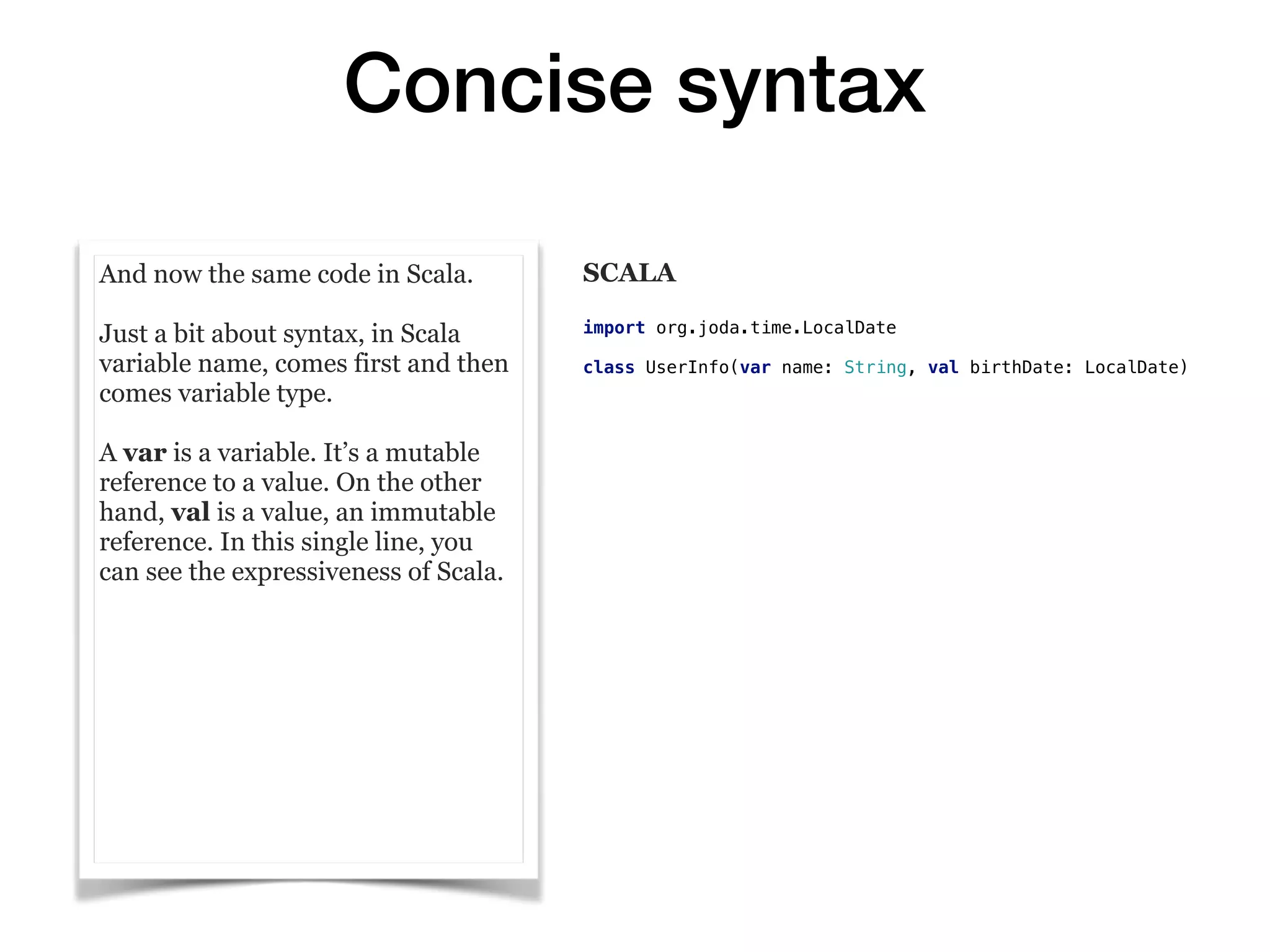

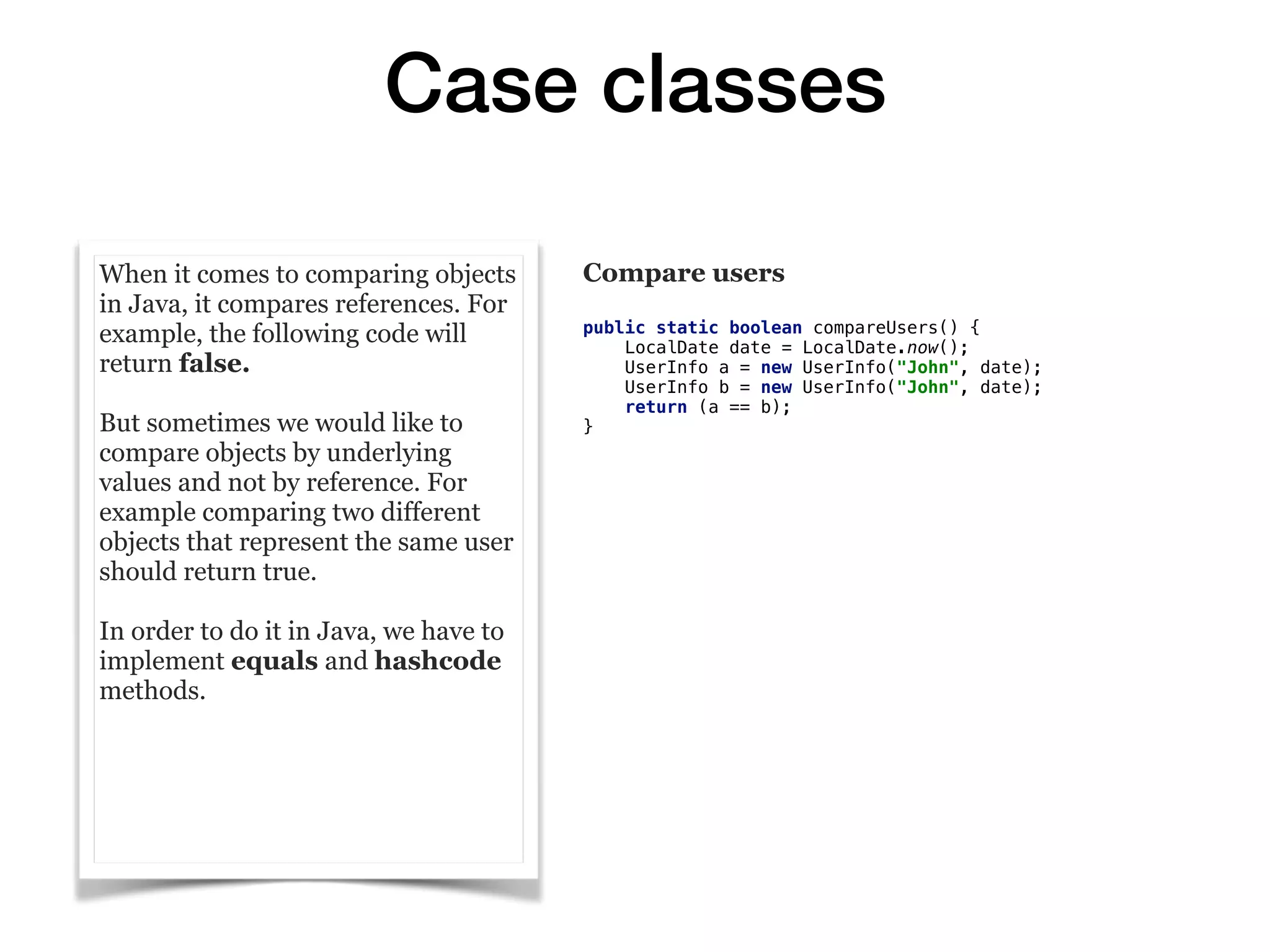

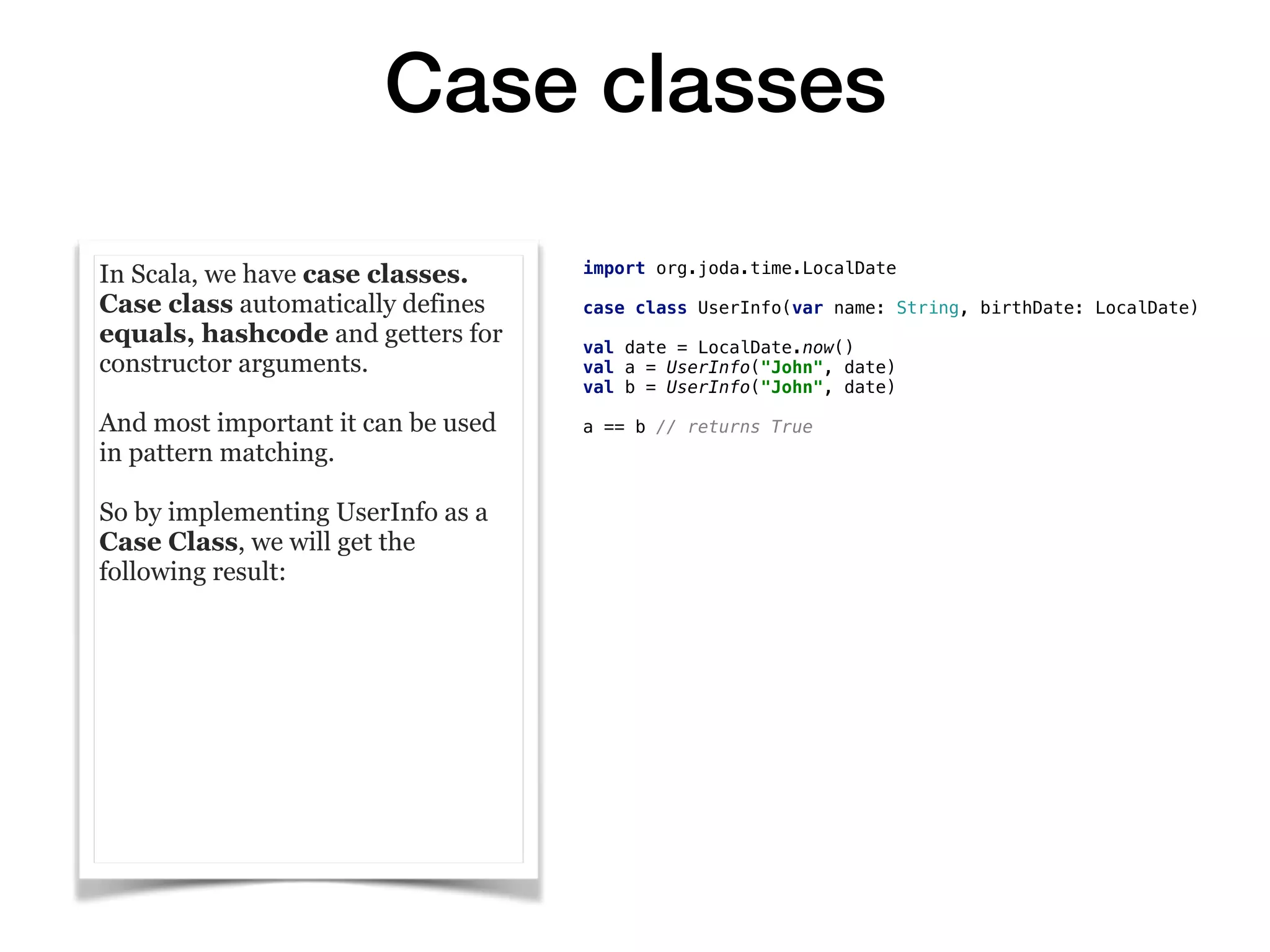

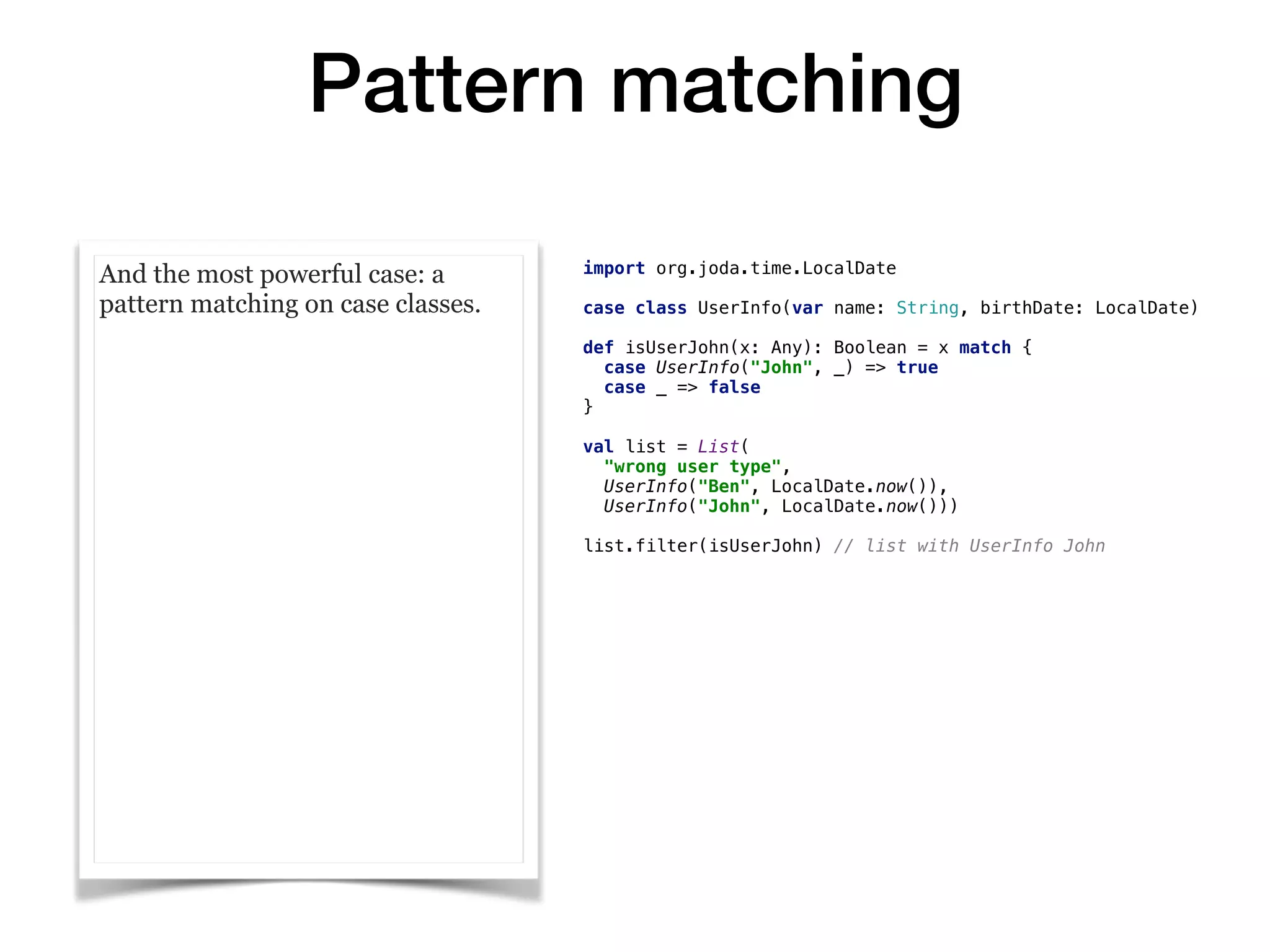

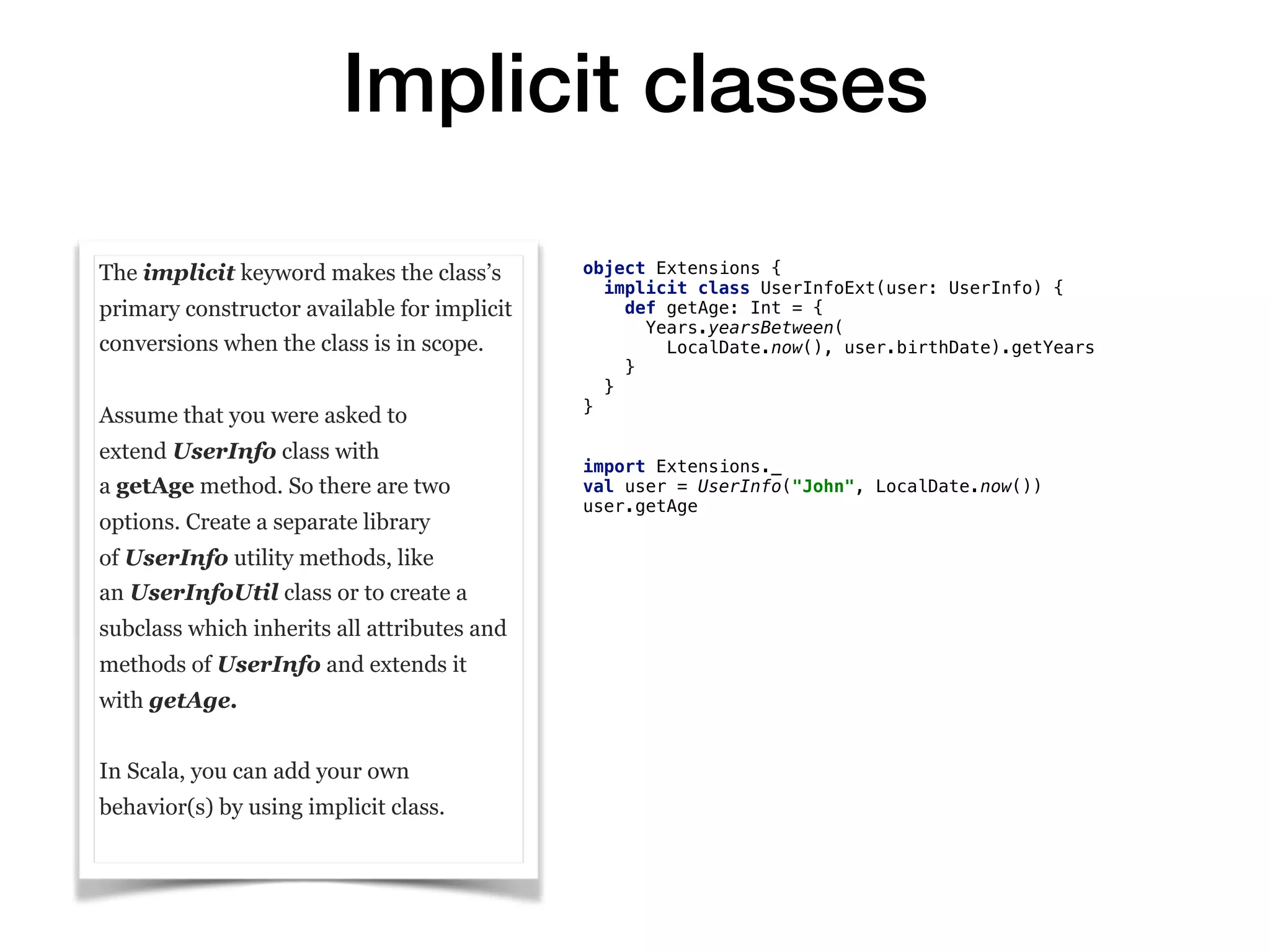

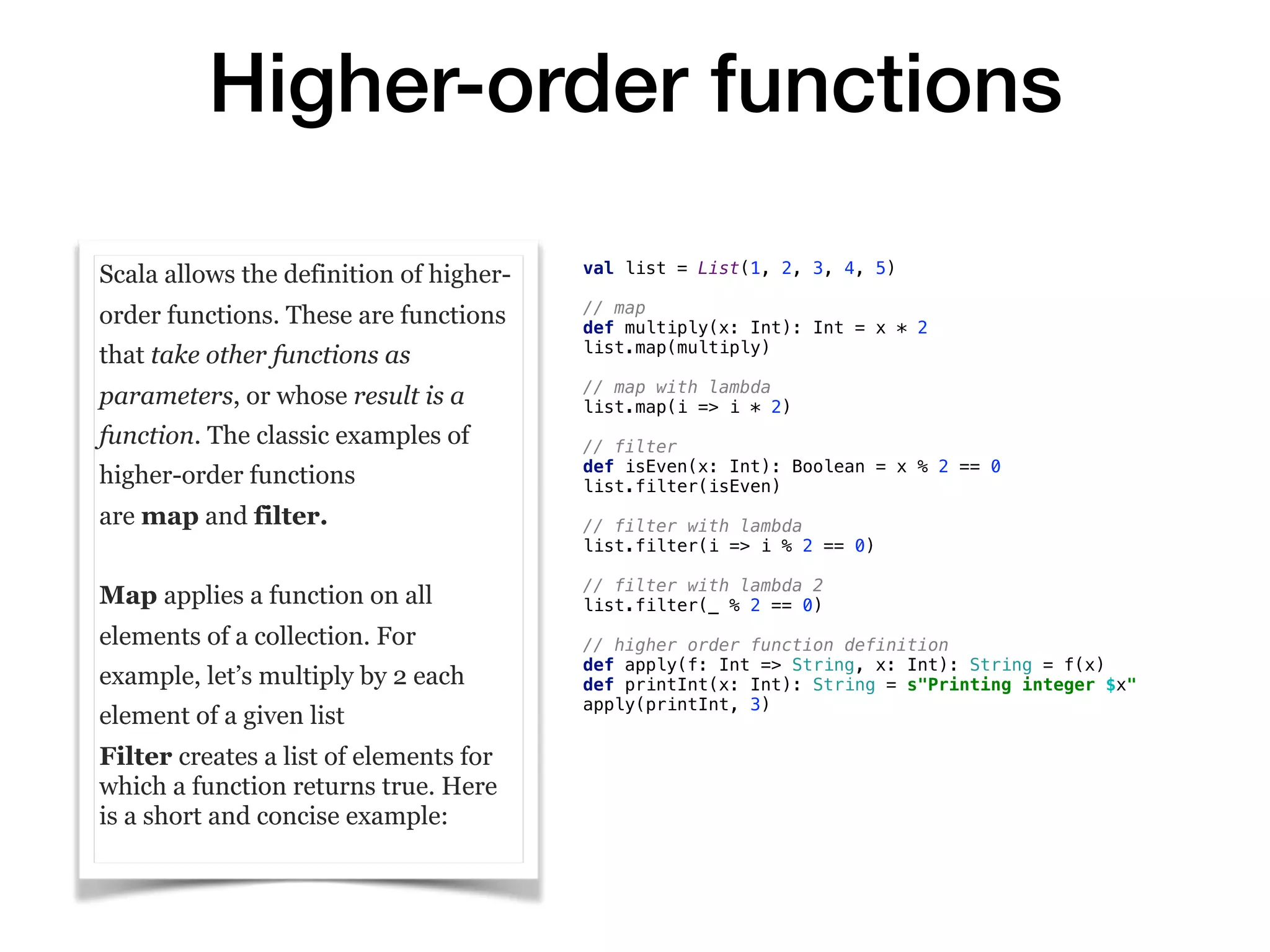

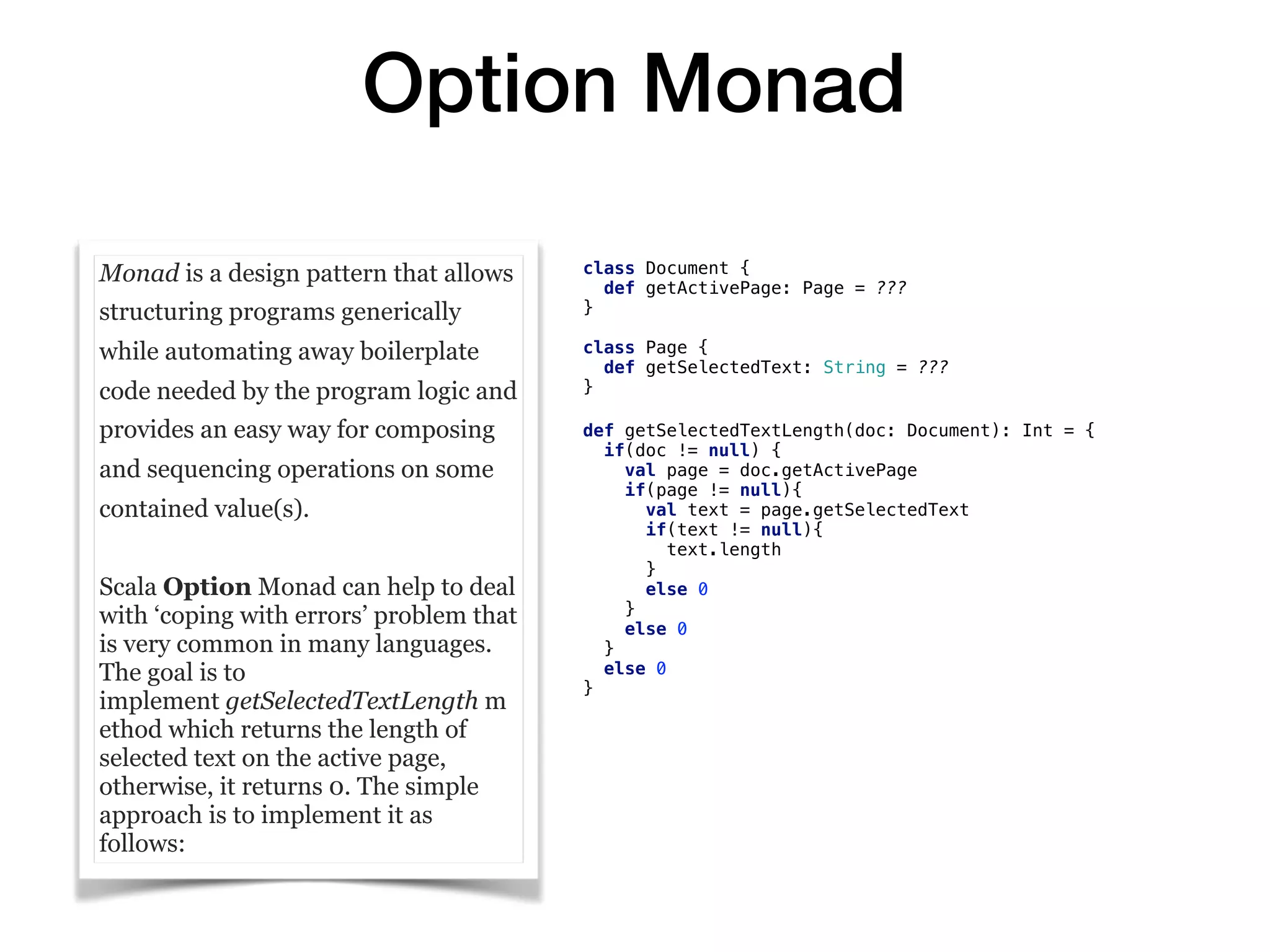

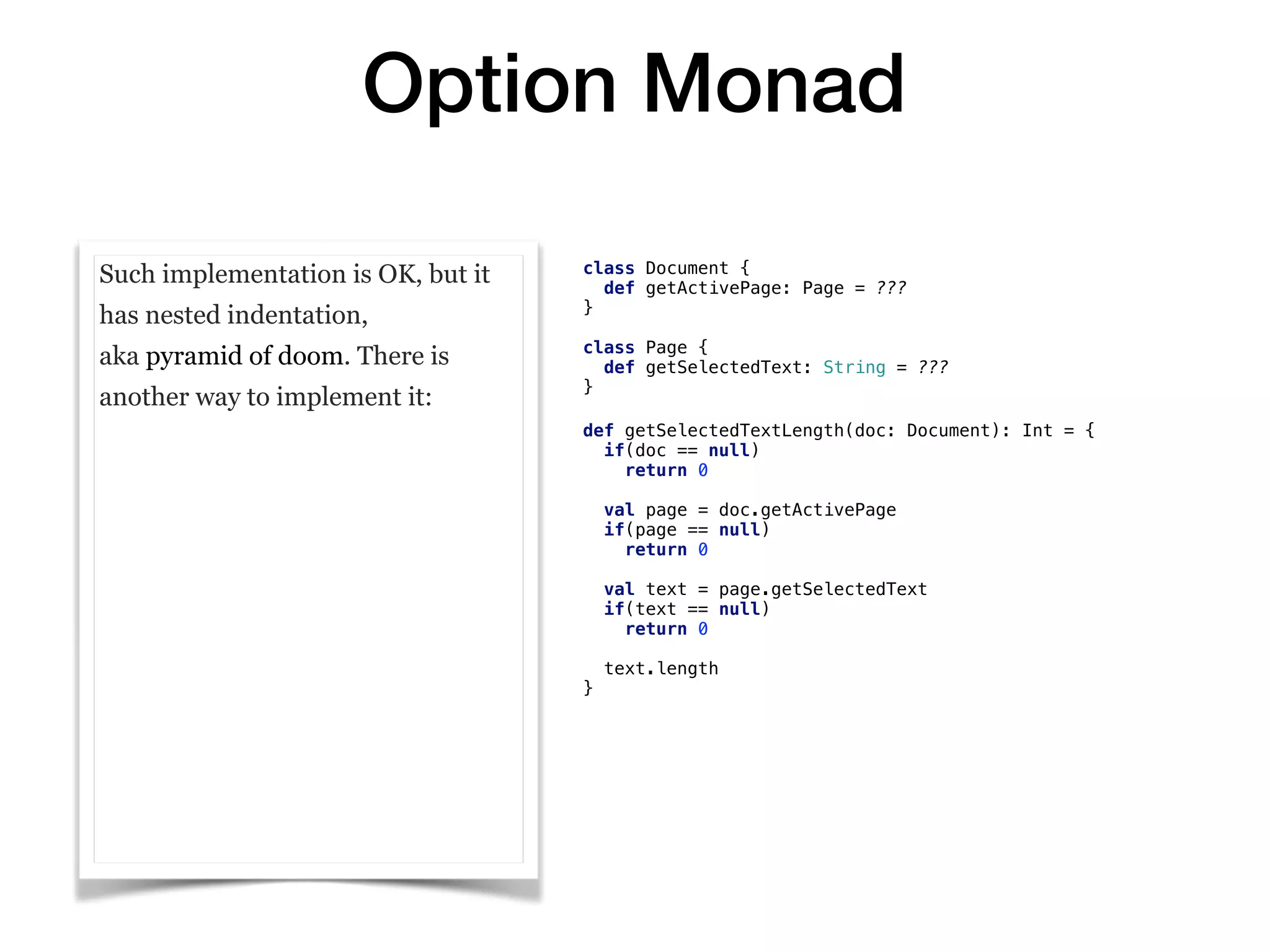

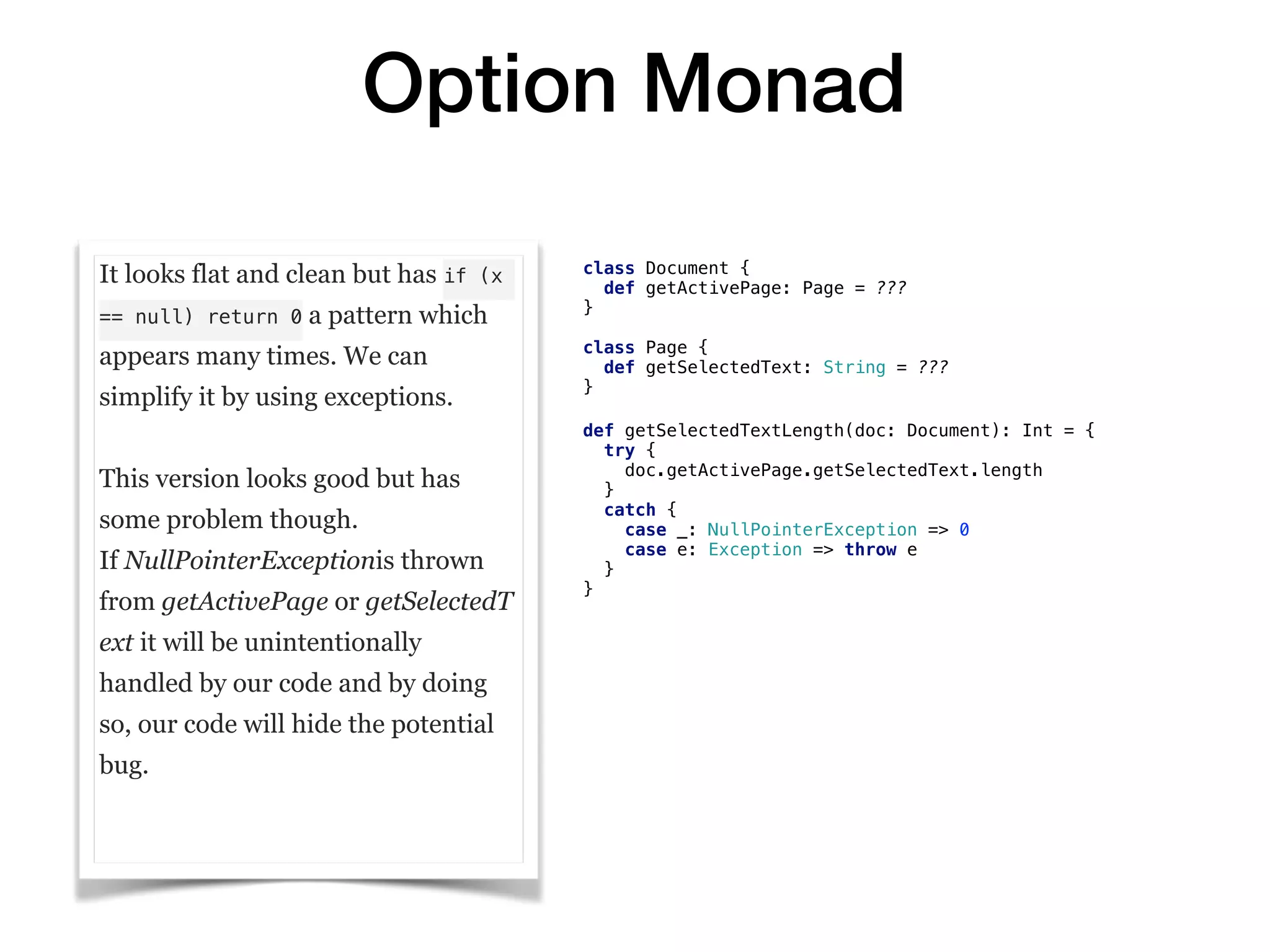

This document provides an overview of a 30-minute Scala tutorial covering Scala's core features like case classes, pattern matching, implicit classes, higher-order functions, and the Option monad. Scala is designed for concise syntax compared to Java, supports both object-oriented and functional programming, and is statically typed on the JVM. The tutorial demonstrates Scala concepts like implicit classes extending functionality, pattern matching for control flow, and using the Option monad to avoid null checks when chaining method calls.

![Pattern matching

Pattern matching is a mechanism

for checking a value against a

pattern.

You can think about Scala’s pattern

matching as a more powerful

version of switch statement in

Java. A match expression has a

value, the match keyword, and at

least one case clause.

In Scala it is possible to perform

pattern matching on types

The more powerful case - matching

integers sequence

// example 1

def matchTest(x: Int): String = x match {

case 1 => "one"

case 2 => "two"

case _ => "many"

}

// example 2

def matchOnType(x: Any): String = x match {

case x: Int => s"$x is integer"

case x: String => s"$x is string"

case _ => "unknown type"

}

matchOnType(1) // returns 1 is integer

matchOnType("1") // returns 1 is string

// example 3

def matchList(x: List[Int]): String = x match {

case List(_) => "a single element list"

case List(_, _) => "a two elements list"

case List(1, _*) => "a list starting with 1"

}

matchList(List(3)) // returns a single elements list

matchList(List(0, 1)) // returns a two elements list

matchList(List(1, 0, 0)) // returns a list starting with 1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pr-190423200412/75/A-Scala-tutorial-9-2048.jpg)

![Option Monad

In Scala it can be solved by

using Option Monad. Option

monad wrappes value of any given

type and have two specific

implementations: None when a

value does not exist (null) or Some

for the existing value, plus it defines

flatMap operation which allows

composing operations sequence

together.

trait Option[A] {

def flatMap[B](f: A => Option[B]): Option[B]

}

case class None[A]() extends Option[A] {

def flatMap[B](f: A => Option[B]): Option[B] = new None

}

case class Some[A](a: A) extends Option[A] {

def flatMap[B](f: A => Option[B]): Option[B] = {

f(a)

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pr-190423200412/75/A-Scala-tutorial-16-2048.jpg)

![Option Monad

In Scala it can be solved by

using Option Monad. Option

monad wrappes value of any given

type and have two specific

implementations: None when a

value does not exist (null) or Some

for the existing value, plus it defines

flatMap operation which allows

composing operations sequence

together.

trait Option[A] {

def flatMap[B](f: A => Option[B]): Option[B]

}

case class None[A]() extends Option[A] {

def flatMap[B](f: A => Option[B]): Option[B] = new None

}

case class Some[A](a: A) extends Option[A] {

def flatMap[B](f: A => Option[B]): Option[B] = {

f(a)

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pr-190423200412/75/A-Scala-tutorial-17-2048.jpg)

![Option Monad

In Scala it can be solved by

using Option Monad. Option

monad wrappes value of any given

type and have two specific

implementations: None when a

value does not exist (null) or Some

for the existing value, plus it defines

flatMap operation which allows

composing operations sequence

together.

trait Option[A] {

def flatMap[B](f: A => Option[B]): Option[B]

}

case class None[A]() extends Option[A] {

def flatMap[B](f: A => Option[B]): Option[B] = new None

}

case class Some[A](a: A) extends Option[A] {

def flatMap[B](f: A => Option[B]): Option[B] = {

f(a)

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pr-190423200412/75/A-Scala-tutorial-18-2048.jpg)

![Option Monad

So by using Option monad, we can

reimplement the code as follows:

class Page {

def getSelectedText: Option[String] = None

}

class Document {

def getActivePage: Option[Page] = None

}

def getSelectedTextLength(doc: Option[Document]): Int = {

doc

.flatMap(_.getActivePage)

.flatMap(_.getSelectedText)

.map(_.length).getOrElse(0)

}

getSelectedTextLength(Some(new Document))](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pr-190423200412/75/A-Scala-tutorial-19-2048.jpg)