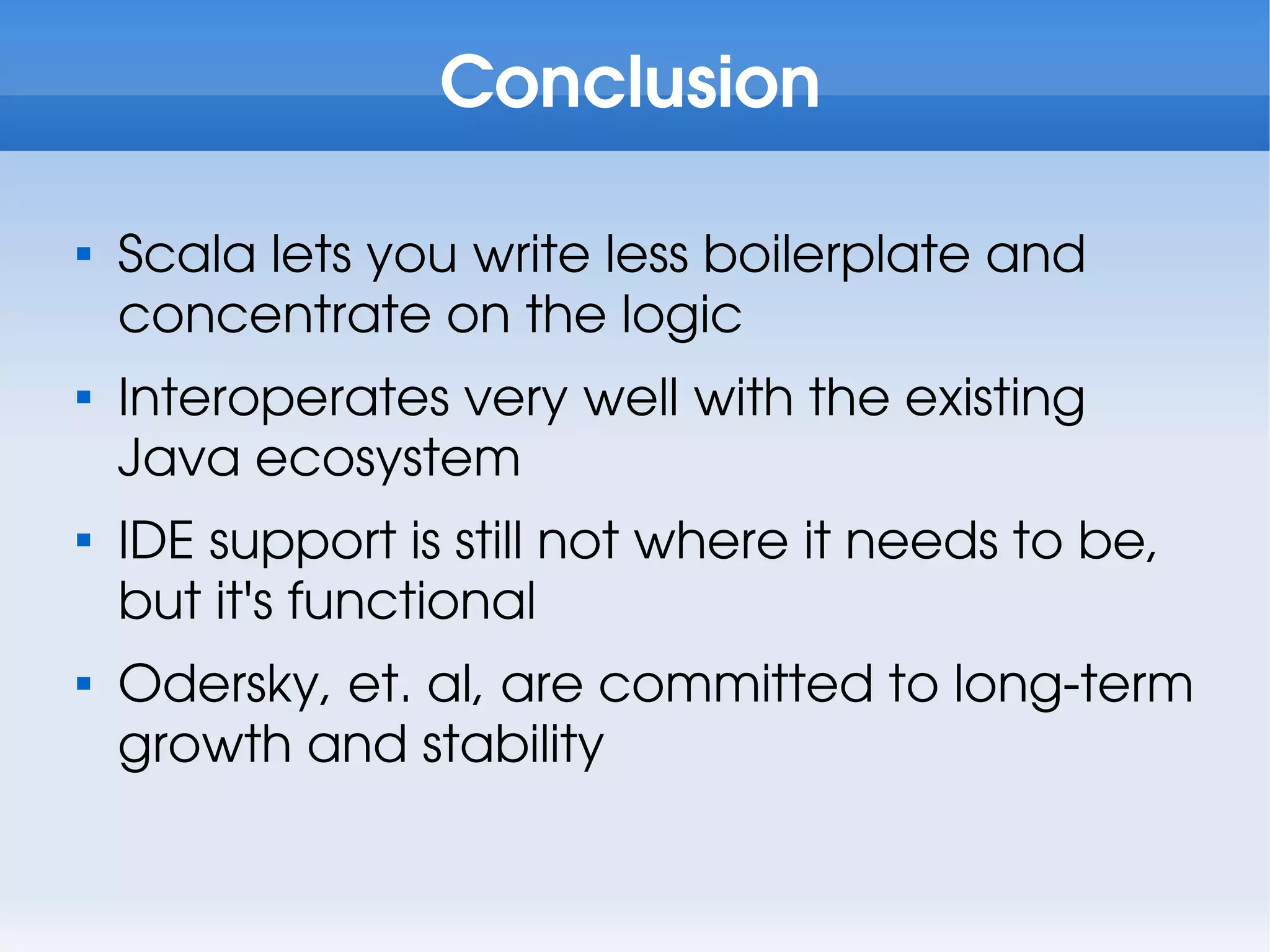

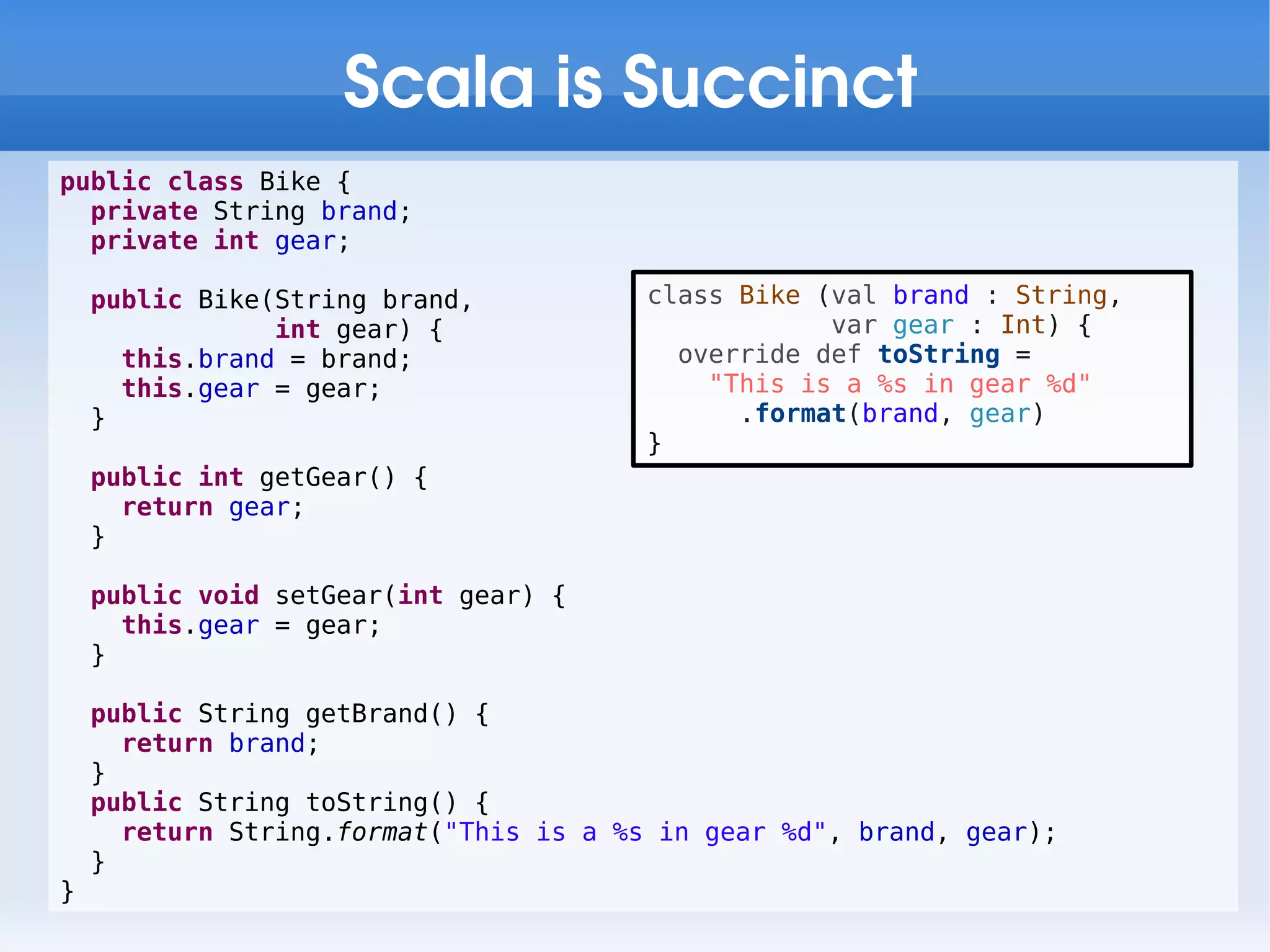

This document provides an overview of Scala, a programming language created by Martin Odersky that offers a blend of object-oriented and functional programming features. It highlights Scala's capabilities such as immutability, first-class functions, pattern matching, and its seamless interfacing with Java. The document concludes by noting Scala's boilerplate reduction, solid Java ecosystem integration, and ongoing commitment to development.

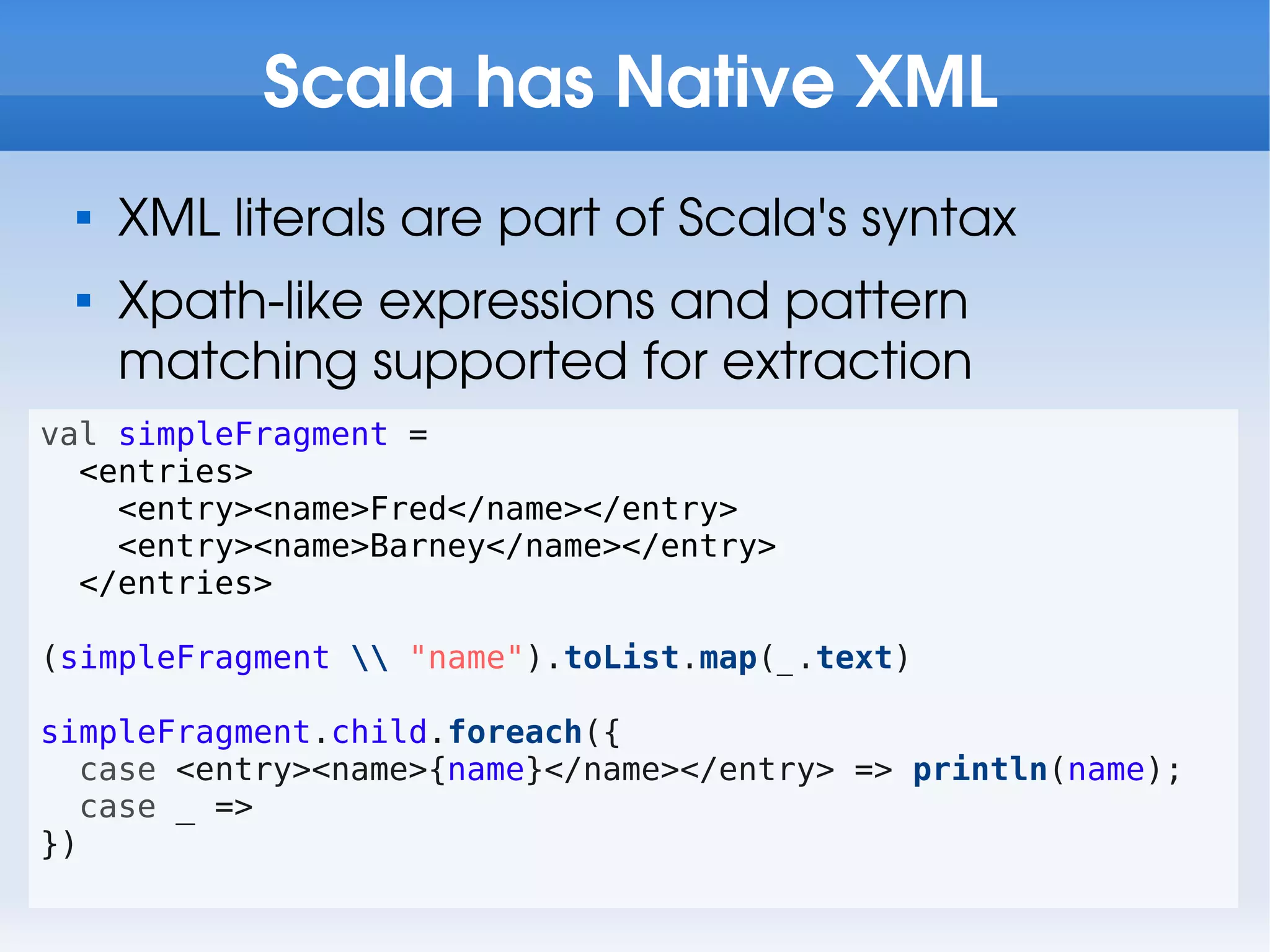

![Scala is Functional, Part 2

Functions (and Scala's type system) allow you

to do things like define new control structures

in a type-safe way:

// Structural typing allows any type with a “close” method

def using[A <: { def close() : Unit }, B]

(resource : A )

(f : A => B) : B =

try {

f(resource)

} finally {

resource.close

}

val firstLine =

using(new BufferedReader(new FileReader("/etc/hosts"))) {

reader => reader.readLine

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/developerdaypreso20091010v2-091012184938-phpapp01/75/Stepping-Up-A-Brief-Intro-to-Scala-9-2048.jpg)

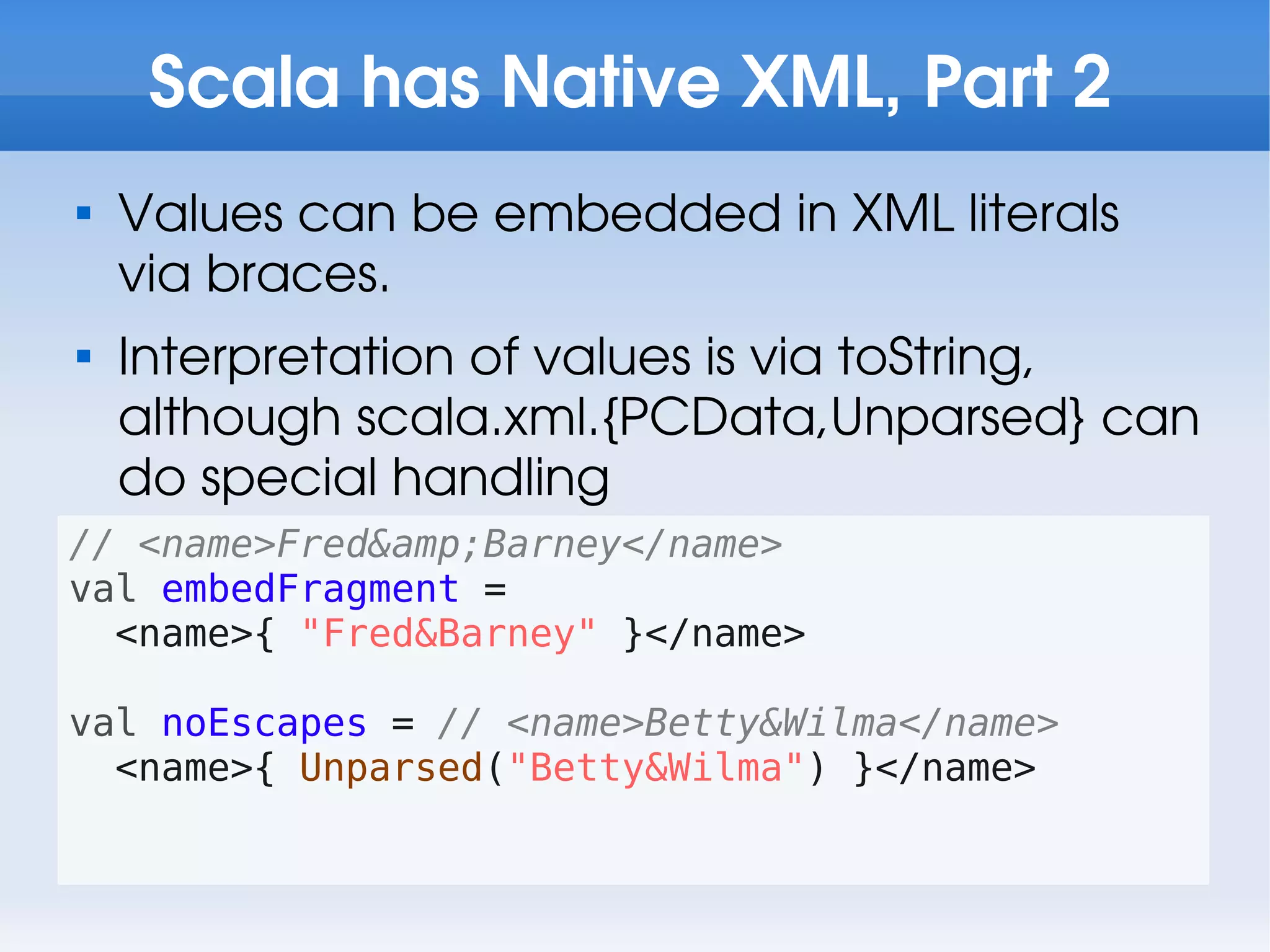

![Scala has For-Comprehensions

For-comprehensions provide an elegant

construct for tying multiple sources and

criteria together to extract information:

val prefixes = List("/tmp", "/work",

System.getProperty("user.home"))

val suffixes = List("txt", "xml", "html")

def locateFiles(name : String) : List[String] =

for (prefix <- prefixes;

suffix <- suffixes;

filename <-

Some("%s/%s.%s".format(prefix, name, suffix))

if (new File(filename)).exists)

yield filename](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/developerdaypreso20091010v2-091012184938-phpapp01/75/Stepping-Up-A-Brief-Intro-to-Scala-12-2048.jpg)