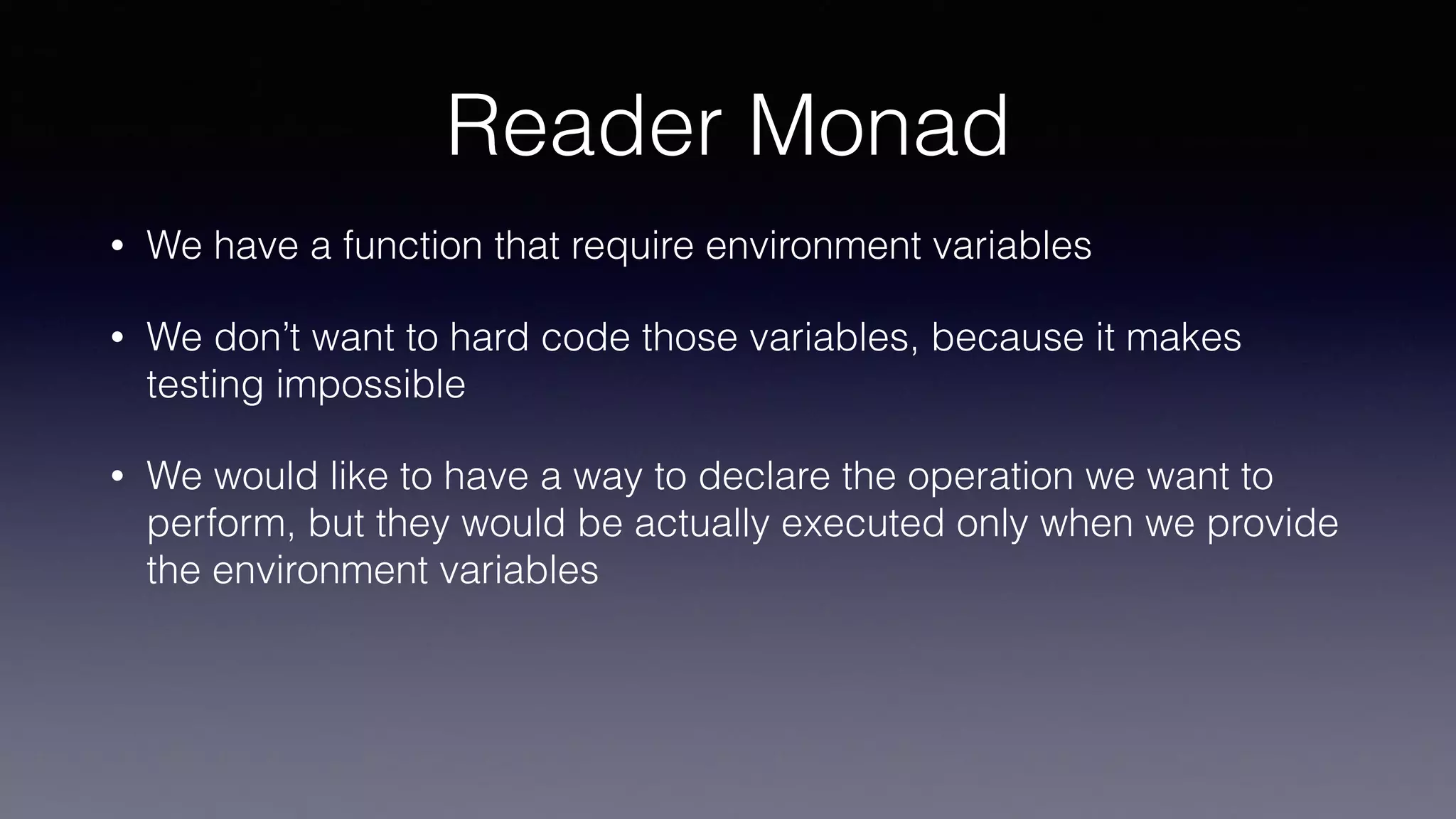

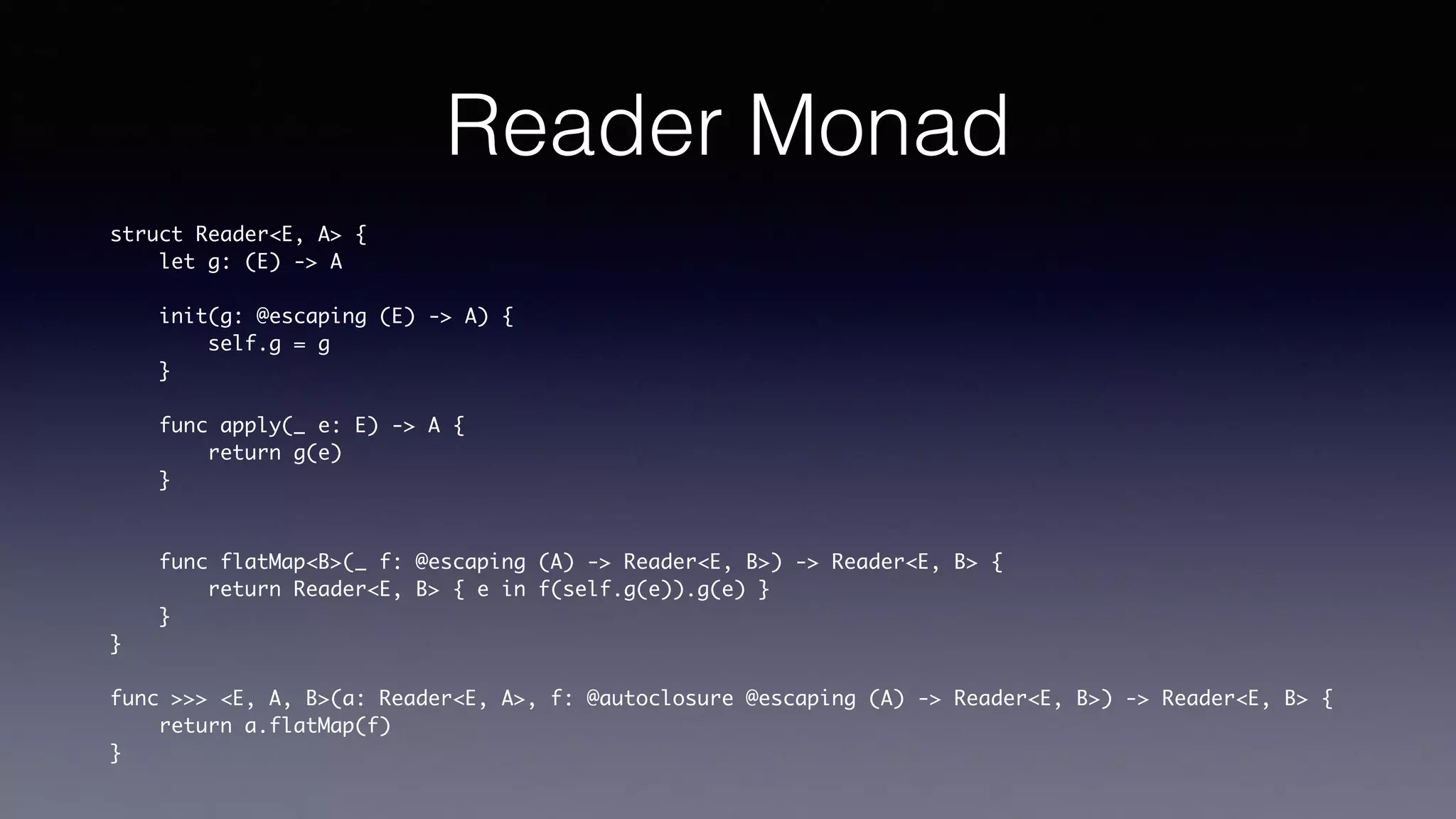

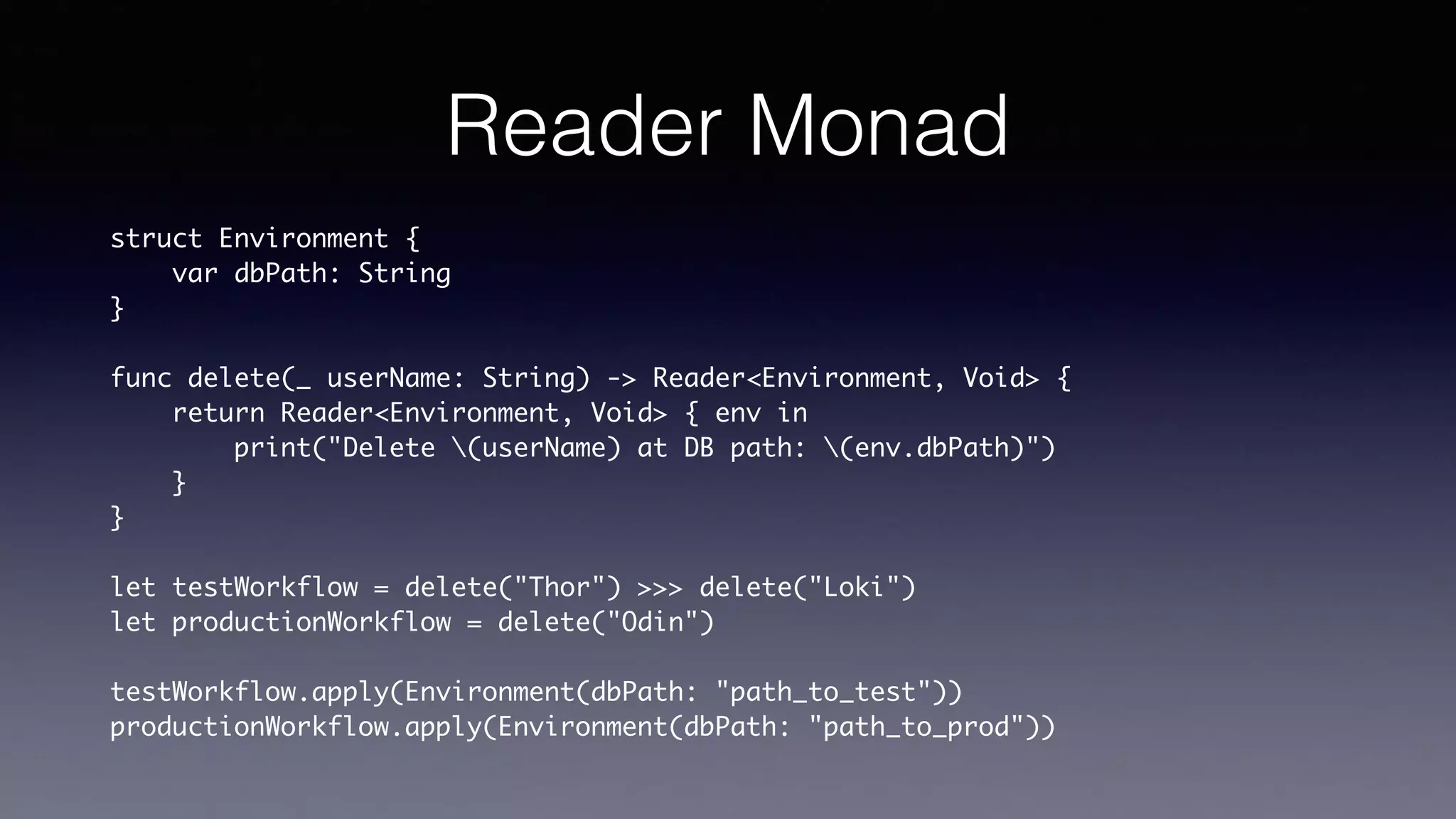

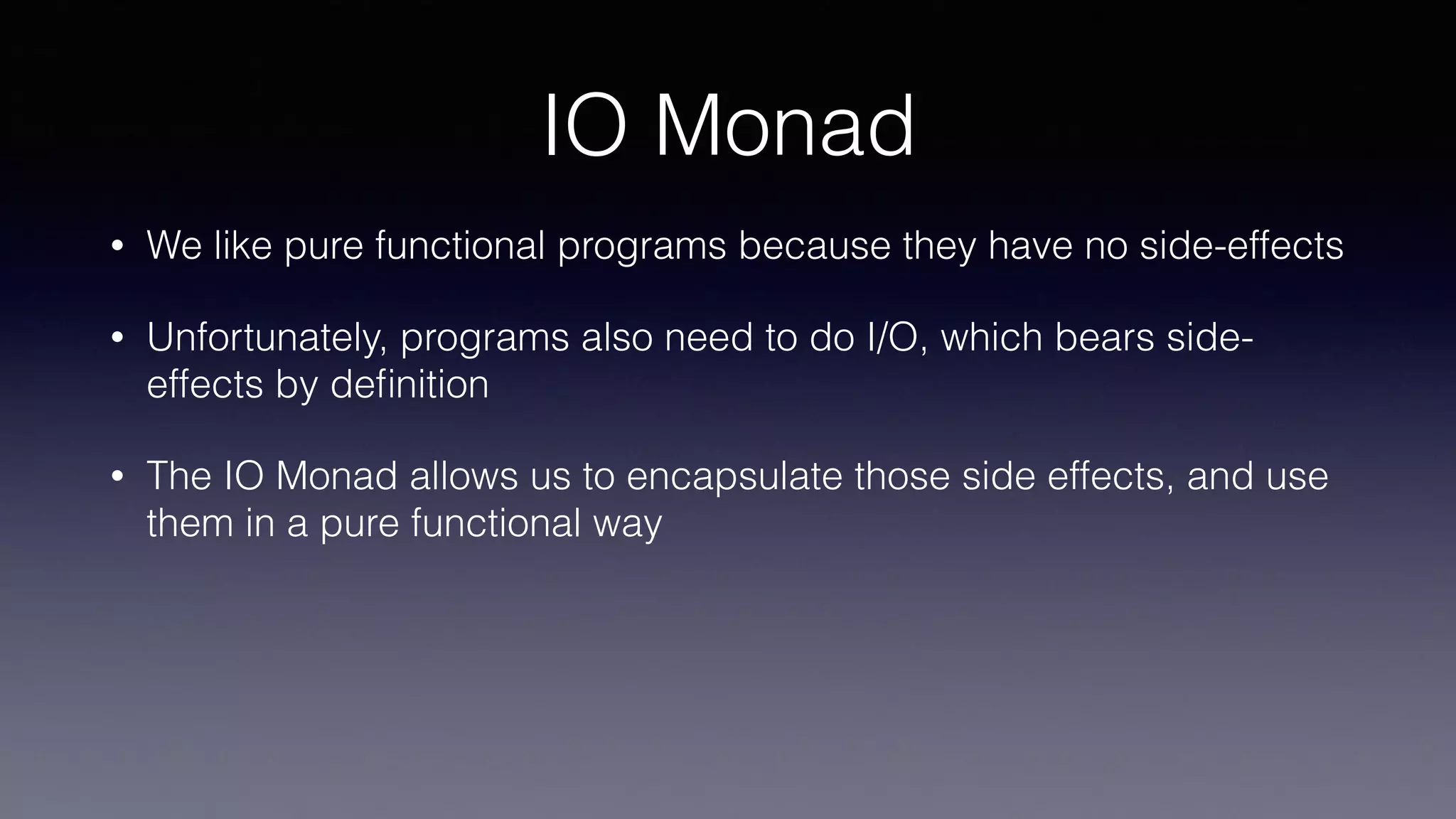

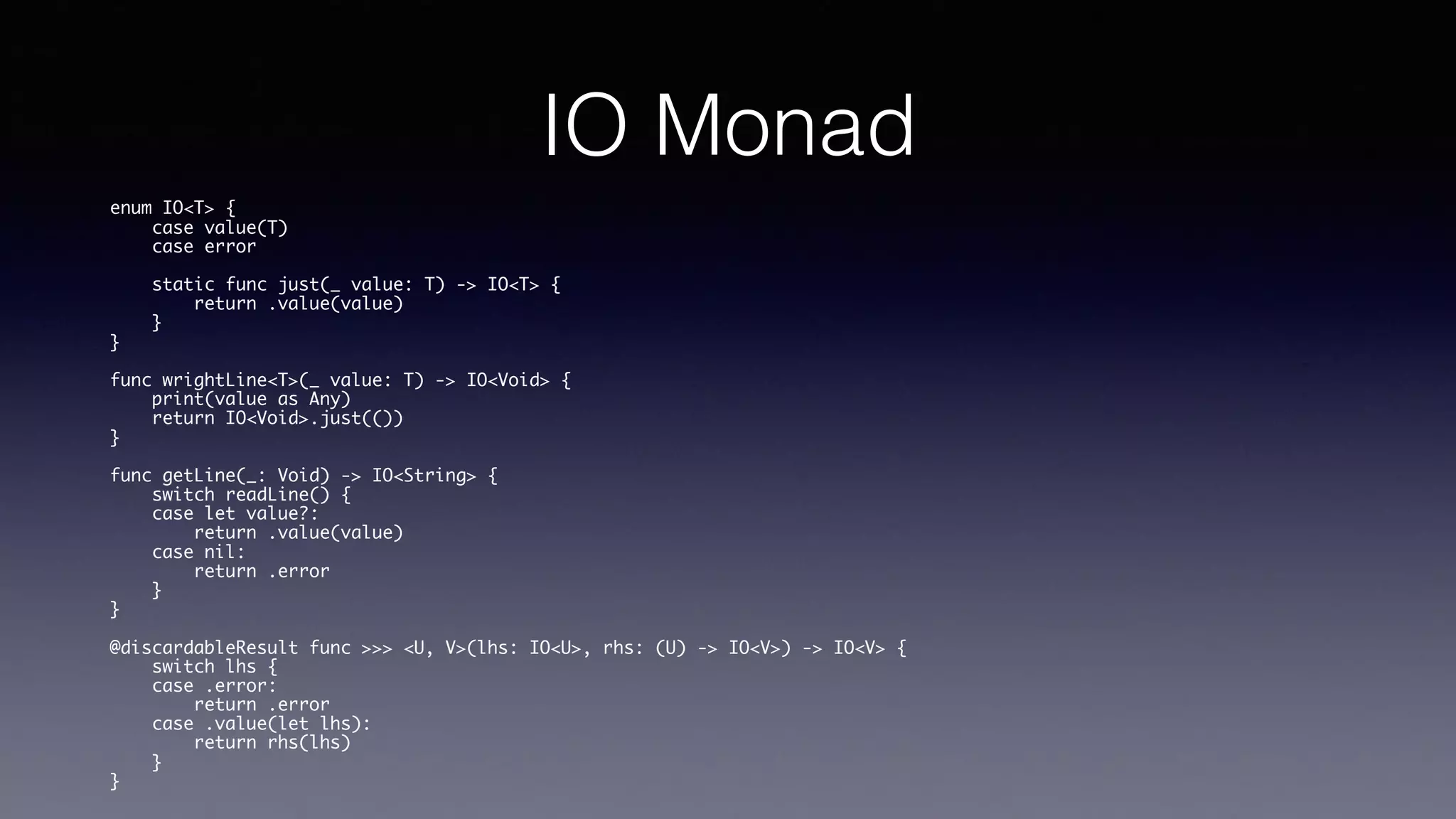

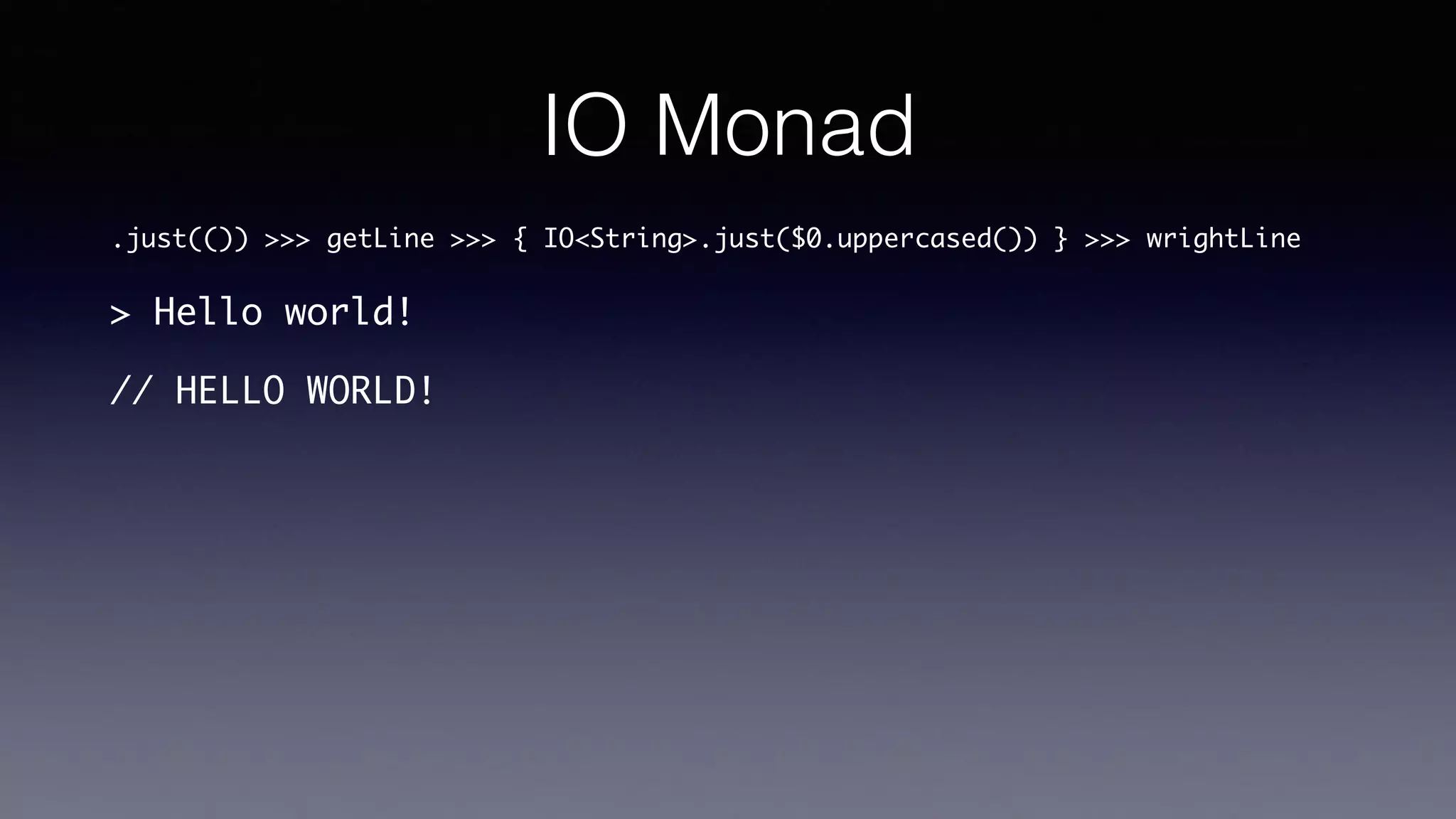

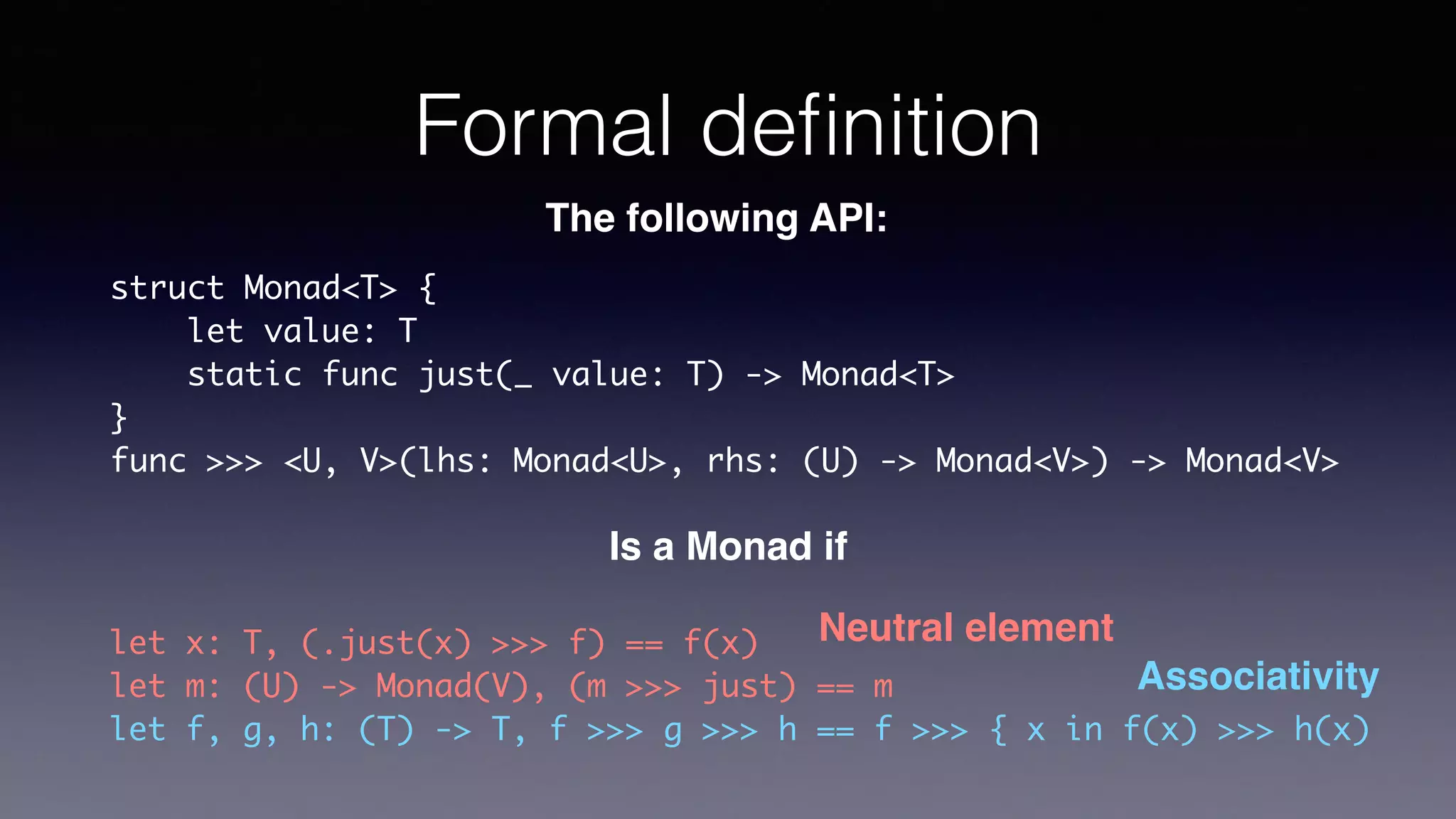

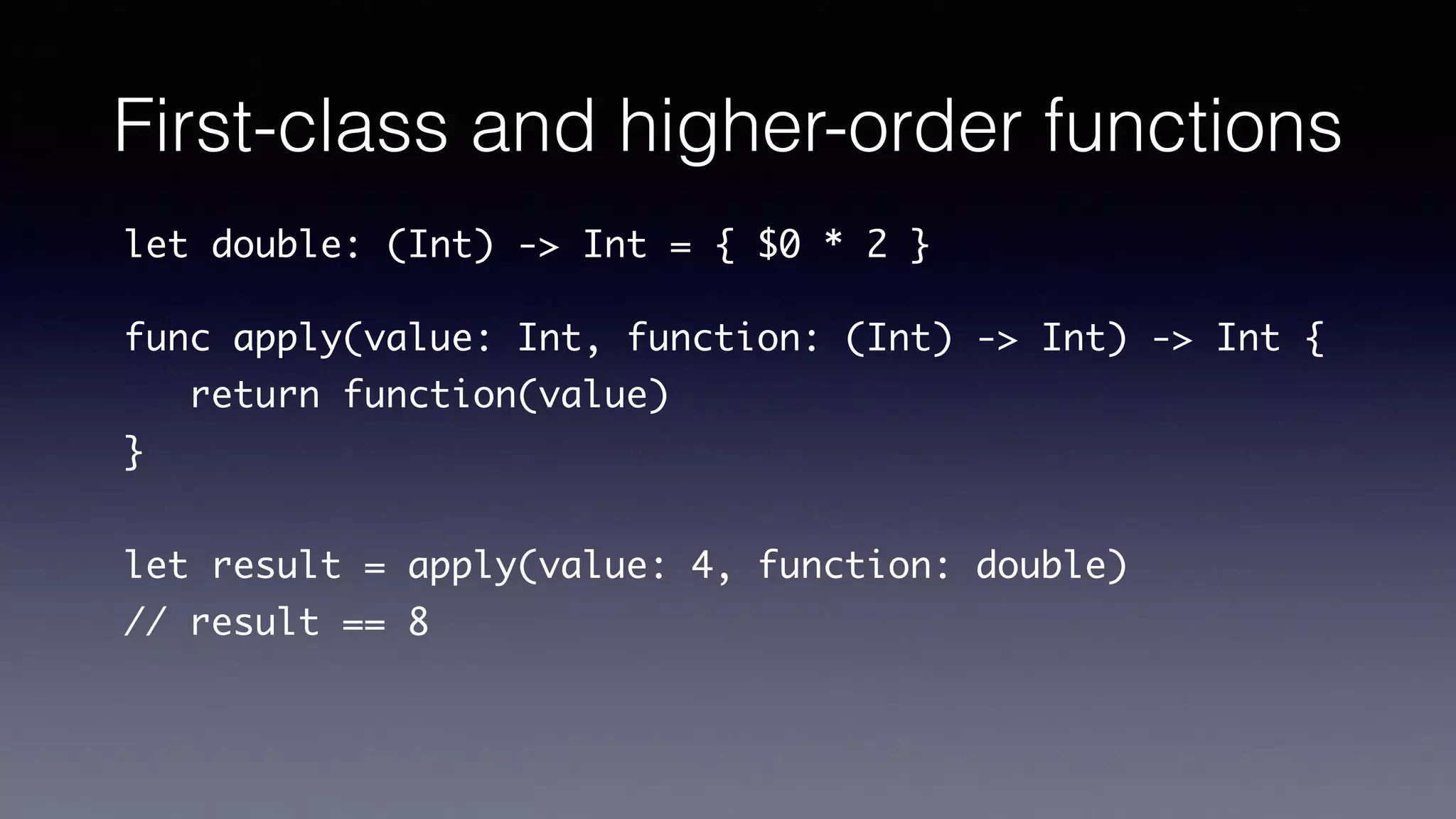

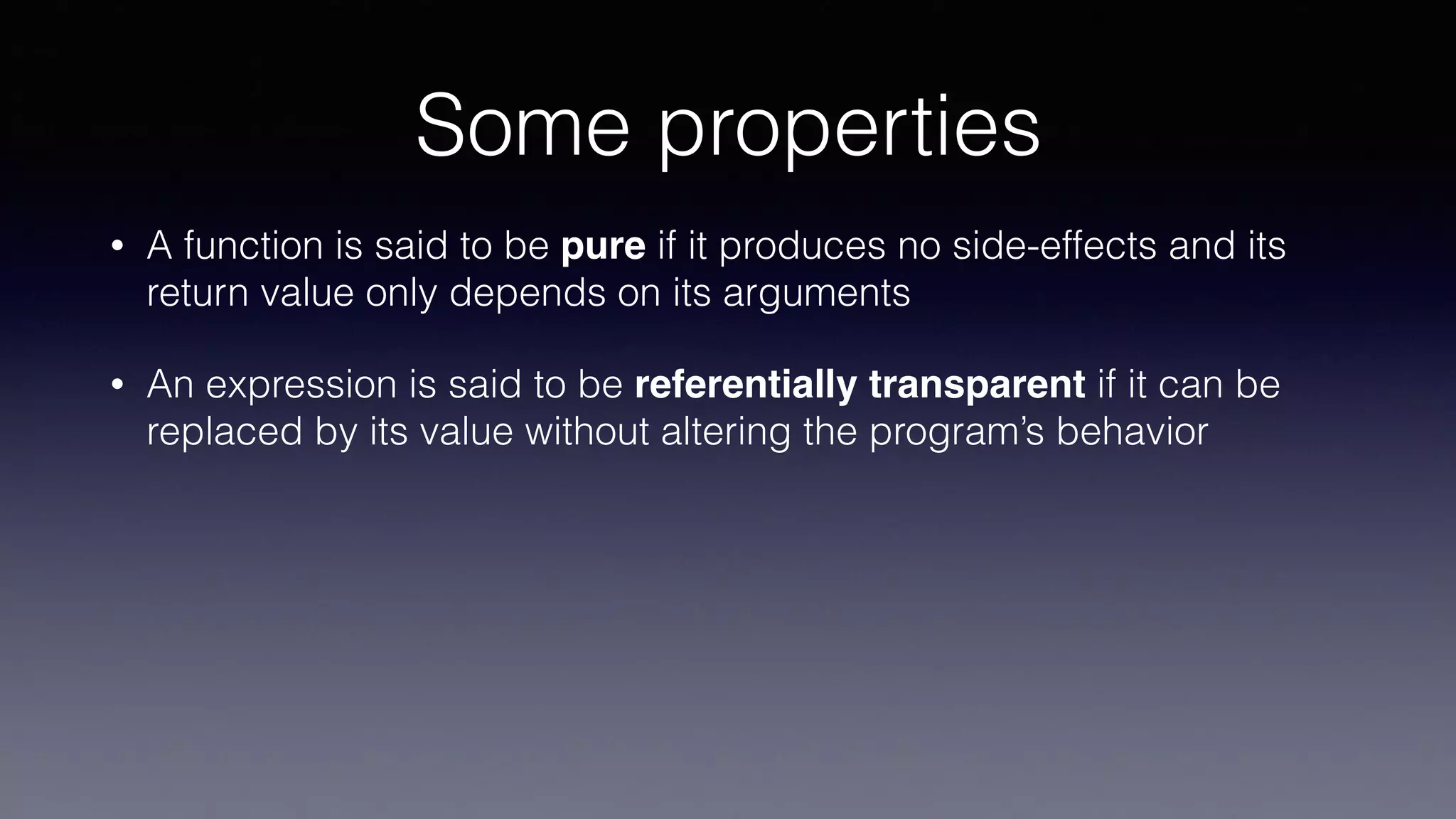

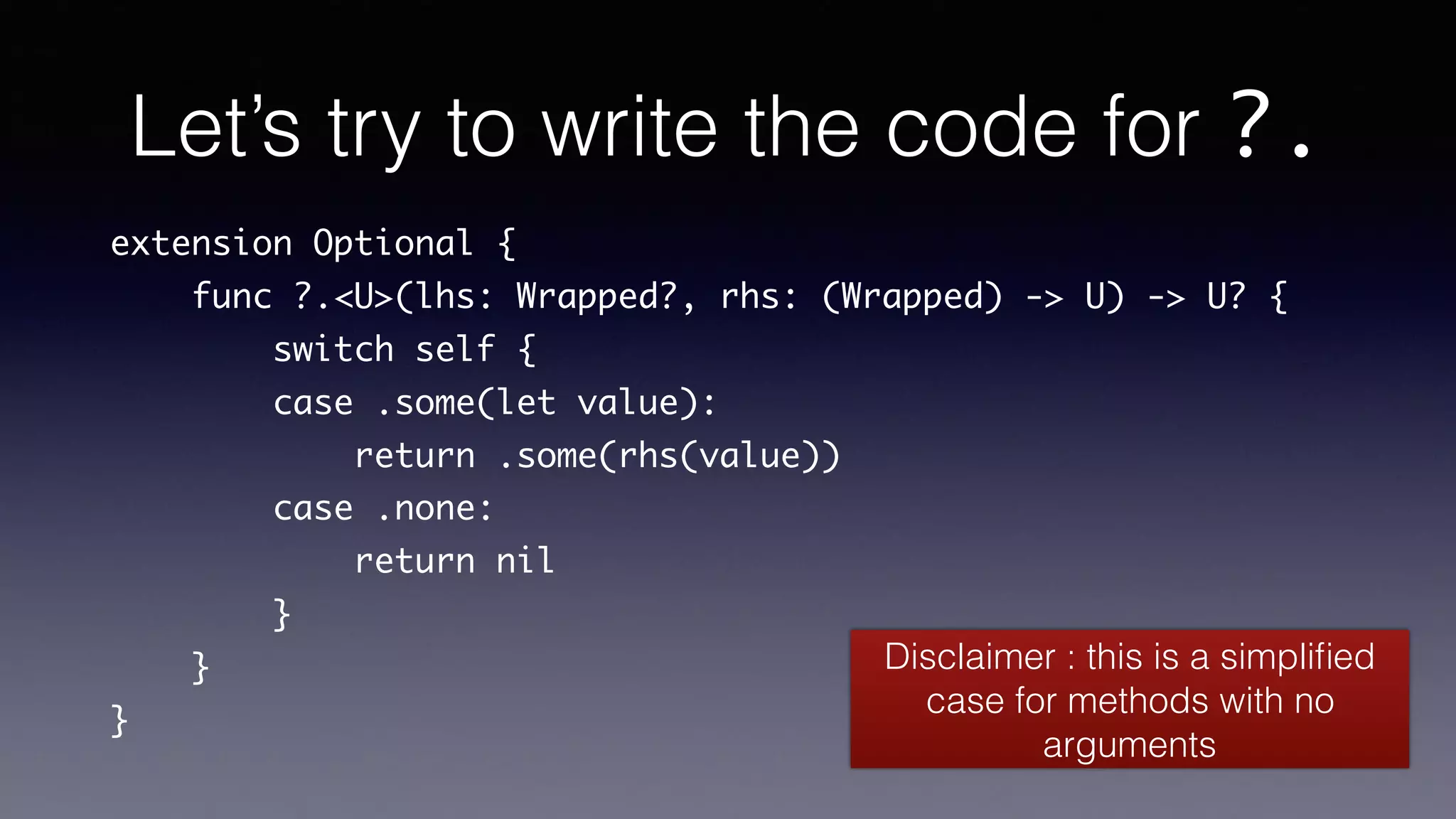

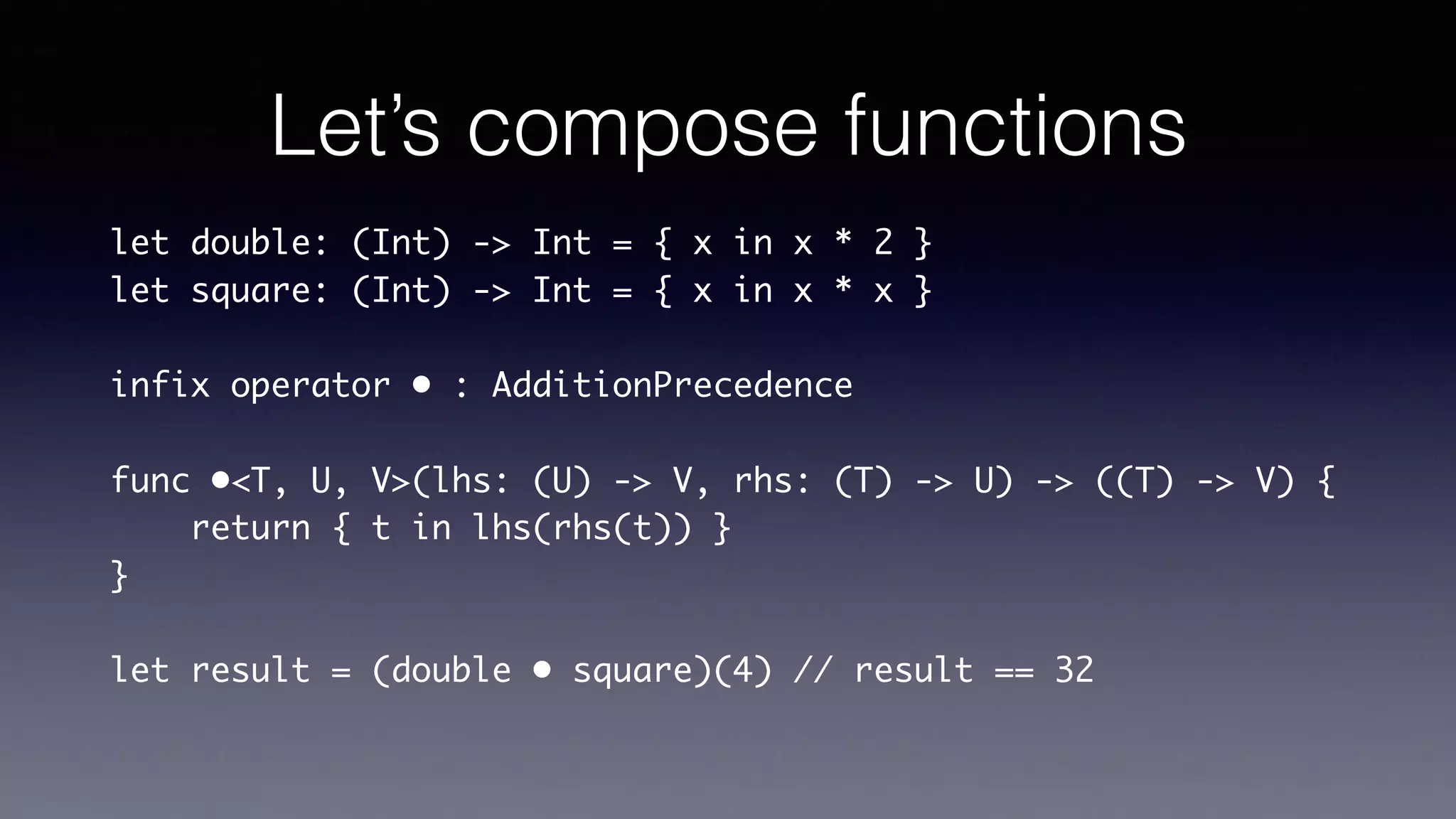

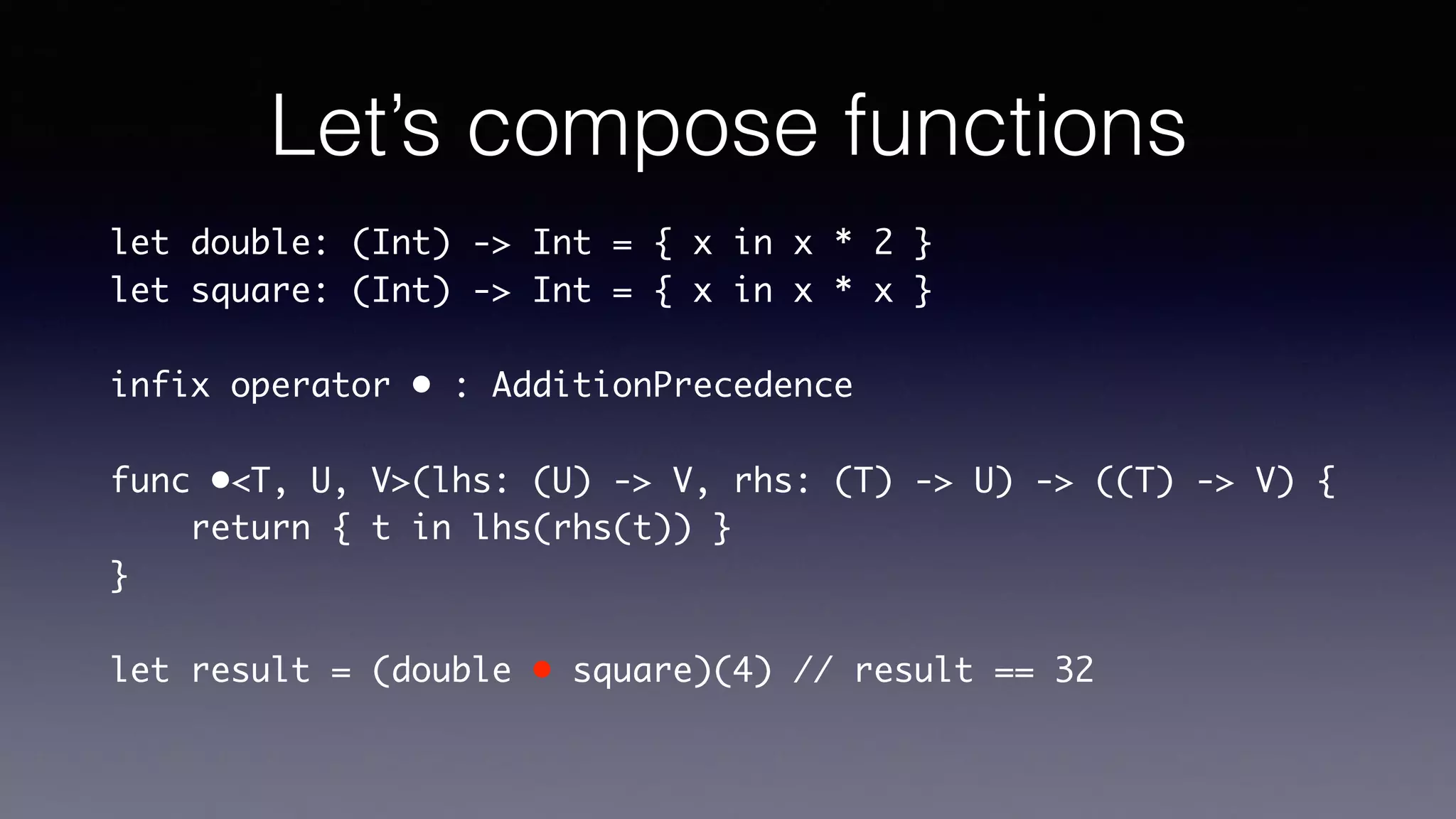

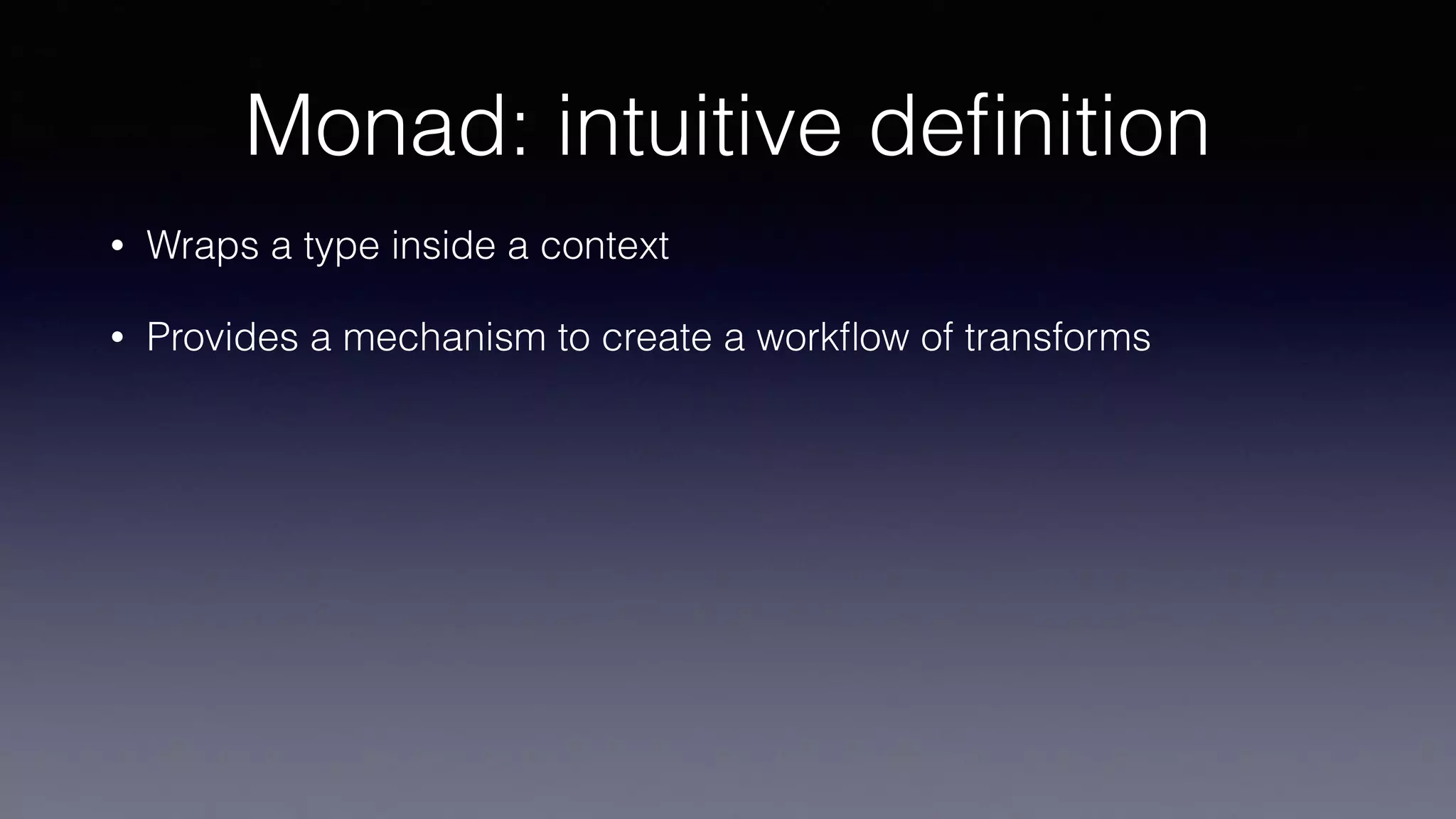

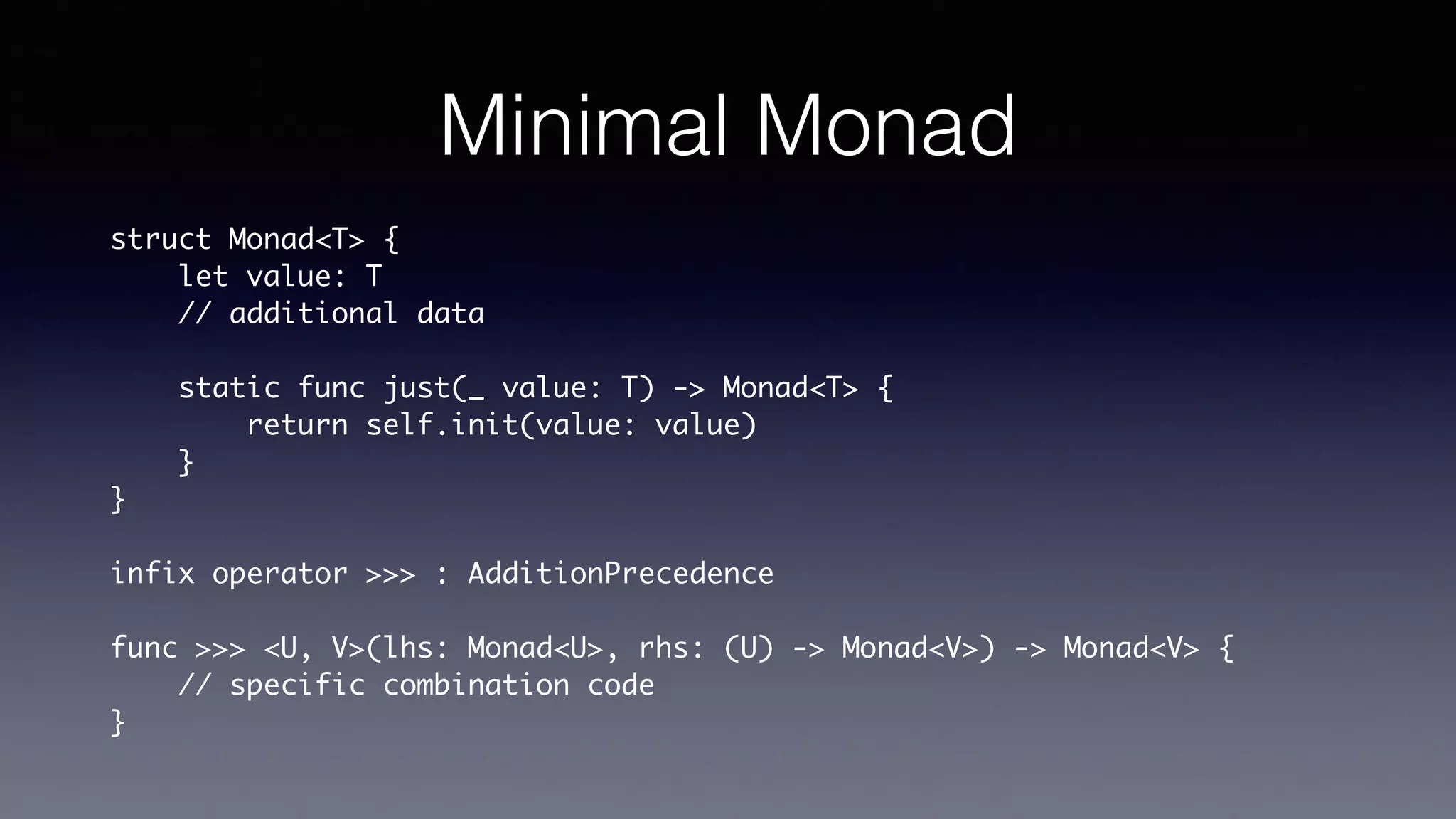

This document discusses monads in functional programming. It provides examples of optionals, arrays, and functions in Swift that exhibit monadic properties. It then defines monads more formally and describes some common monad types like the writer, reader, and IO monads. It shows how monads allow encapsulating effects like logging or environment variables while preserving referential transparency. The document concludes by discussing potential applications of monads to mobile apps.

![Some very familiar code

var data: [String]?

// ...

let result = data?.first?.uppercased()](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/monads-170803173148/75/Monads-in-Swift-6-2048.jpg)

![Some very familiar code

var data: [String]?

// ...

let result = data?.first?.uppercased()

The operator ?. allows us to declare a workflow that will be executed

in order, and will prematurely stop if a nil value is encountered](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/monads-170803173148/75/Monads-in-Swift-7-2048.jpg)

![Let’s manipulate an Array

let data: [Int] = [0, 1, 2]

let result = data.map { $0 * 2 }.map { $0 * $0 }](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/monads-170803173148/75/Monads-in-Swift-10-2048.jpg)

![Let’s manipulate an Array

let data: [Int] = [0, 1, 2]

let result = data.map { $0 * 2 }.map { $0 * $0 }

Same thing here: the function map allows us to declare a workflow](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/monads-170803173148/75/Monads-in-Swift-11-2048.jpg)

![A possible implementation for map

extension Array {

func map<U>(_ transform: (Element) -> U) -> [U] {

var result: [U] = []

for e in self {

result.append(transform(e))

}

return result

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/monads-170803173148/75/Monads-in-Swift-12-2048.jpg)

![Writer Monad

struct Logged<T> {

let value: T

let logs: [String]

private init(value: T) {

self.value = value

self.logs = ["initialized with value: (self.value)"]

}

static func just(_ value: T) -> Logged<T> {

return Logged(value: value)

}

}

func >>> <U, V>(lhs: Logged<U>, rhs: (U) -> Logged<V>) -> Logged<V> {

let computation = rhs(lhs.value)

return Logged<V>(value: computation.value, logs: lhs.logs + computation.logs)

}

func square(_ value: Int) -> Logged<Int> {

let result = value * value

return Logged(value: result, log: "(value) was squared, result: (result)")

}

func halve(_ value: Int) -> Logged<Int> {

let result = value / 2

return Logged(value: result, log: "(value) was halved, result: (result)")

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/monads-170803173148/75/Monads-in-Swift-22-2048.jpg)

![Writer Monad

let computation = .just(4) >>> square >>> halve

print(computation)

// Logged<Int>(value: 8, logs: ["initialized with value:

4", "4 was squared, result: 16", "16 was halved, result:

8"])](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/monads-170803173148/75/Monads-in-Swift-23-2048.jpg)