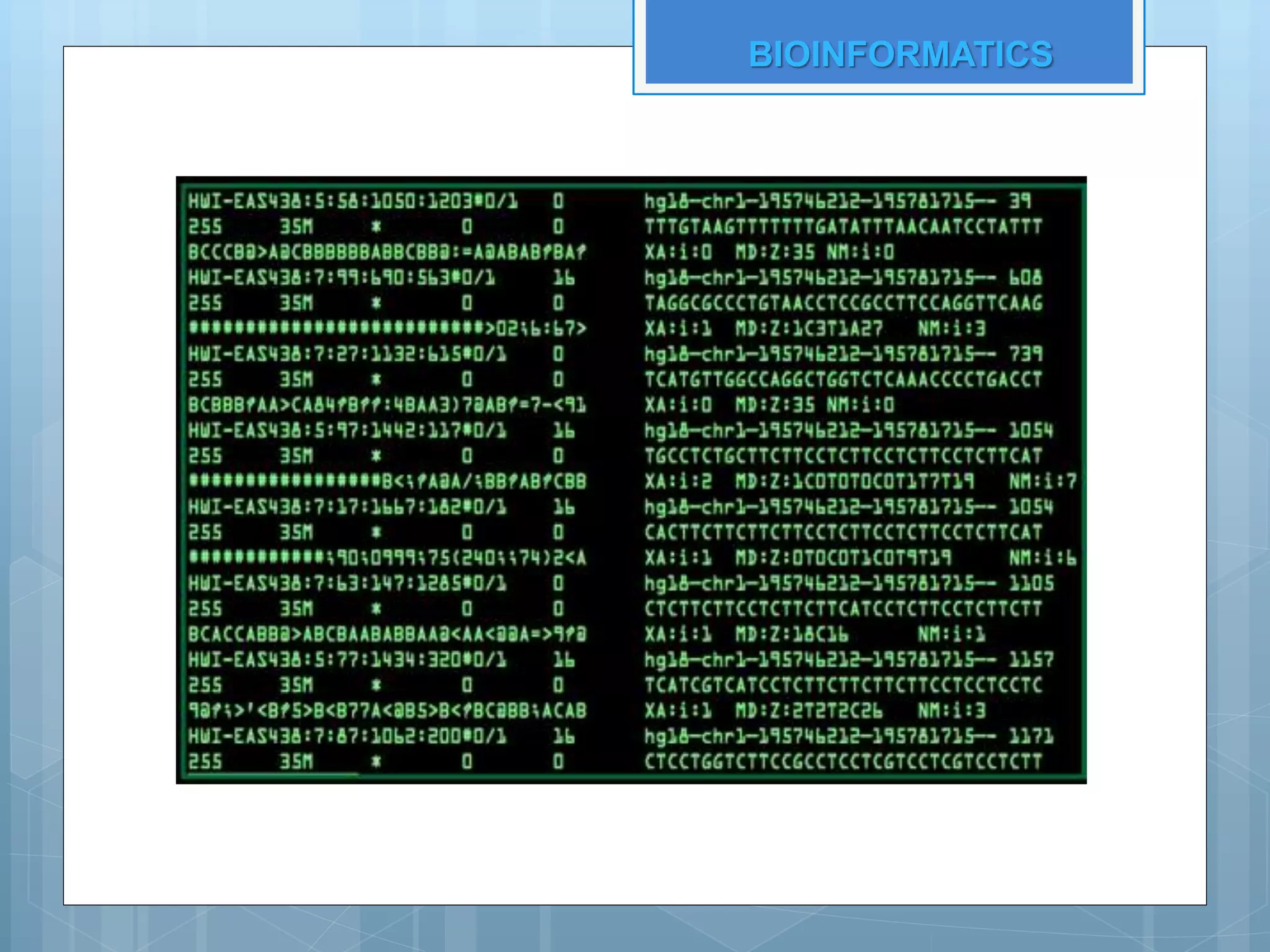

Computational genomics uses computational and statistical analysis to understand biology from genome sequences and related data. It involves analyzing whole genomes to understand how DNA controls organisms' molecular biology. The field emerged in the late 1990s with available complete genomes. It has contributed to discoveries like predicting gene locations, signaling networks, and genome evolution mechanisms. The first computer model of an organism was of Mycoplasma genitalium incorporating over 1,900 parameters. Computational genomics addresses problems like data storage, pattern matching, and structure prediction to analyze vast genomic data from databases.