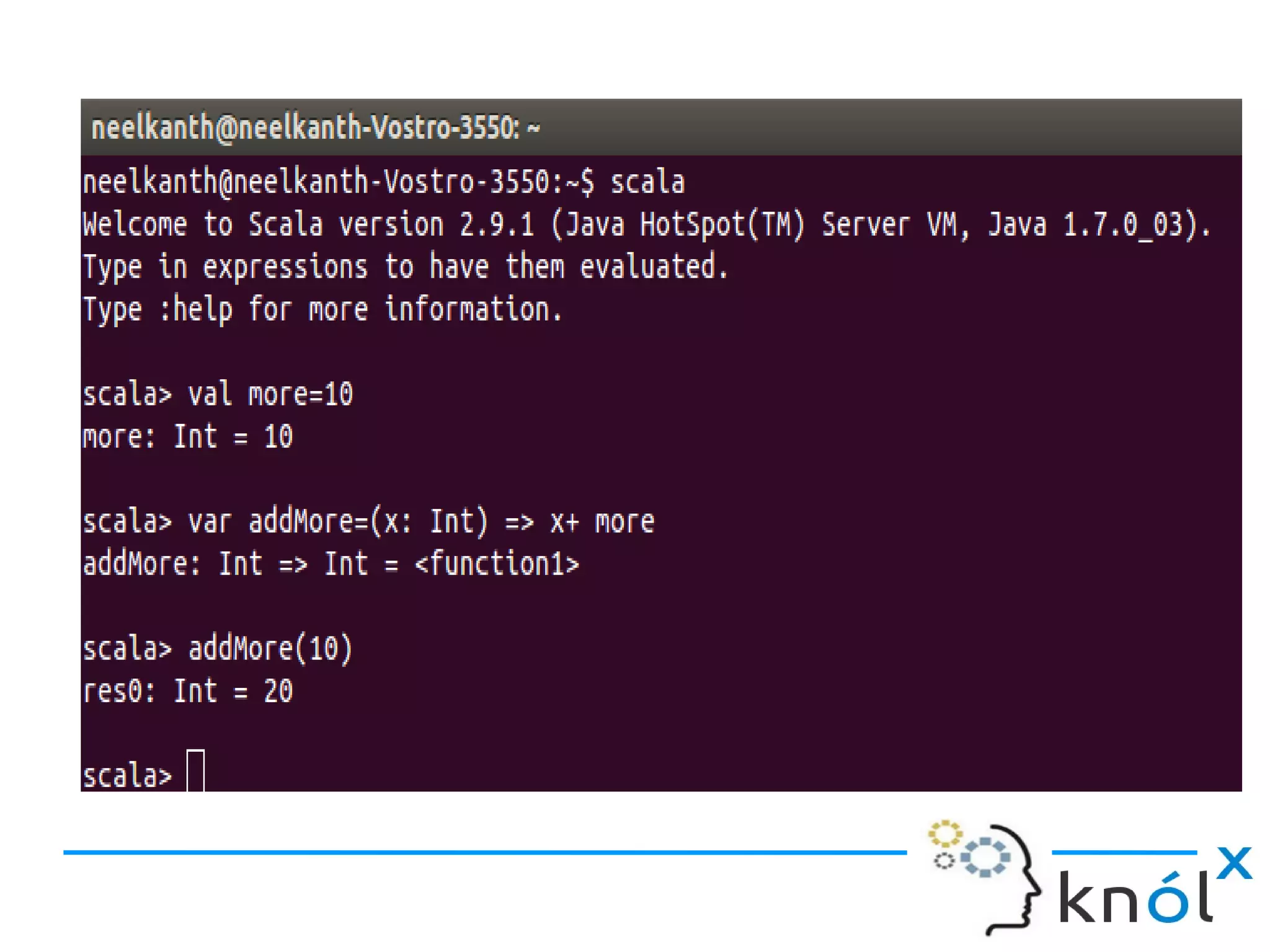

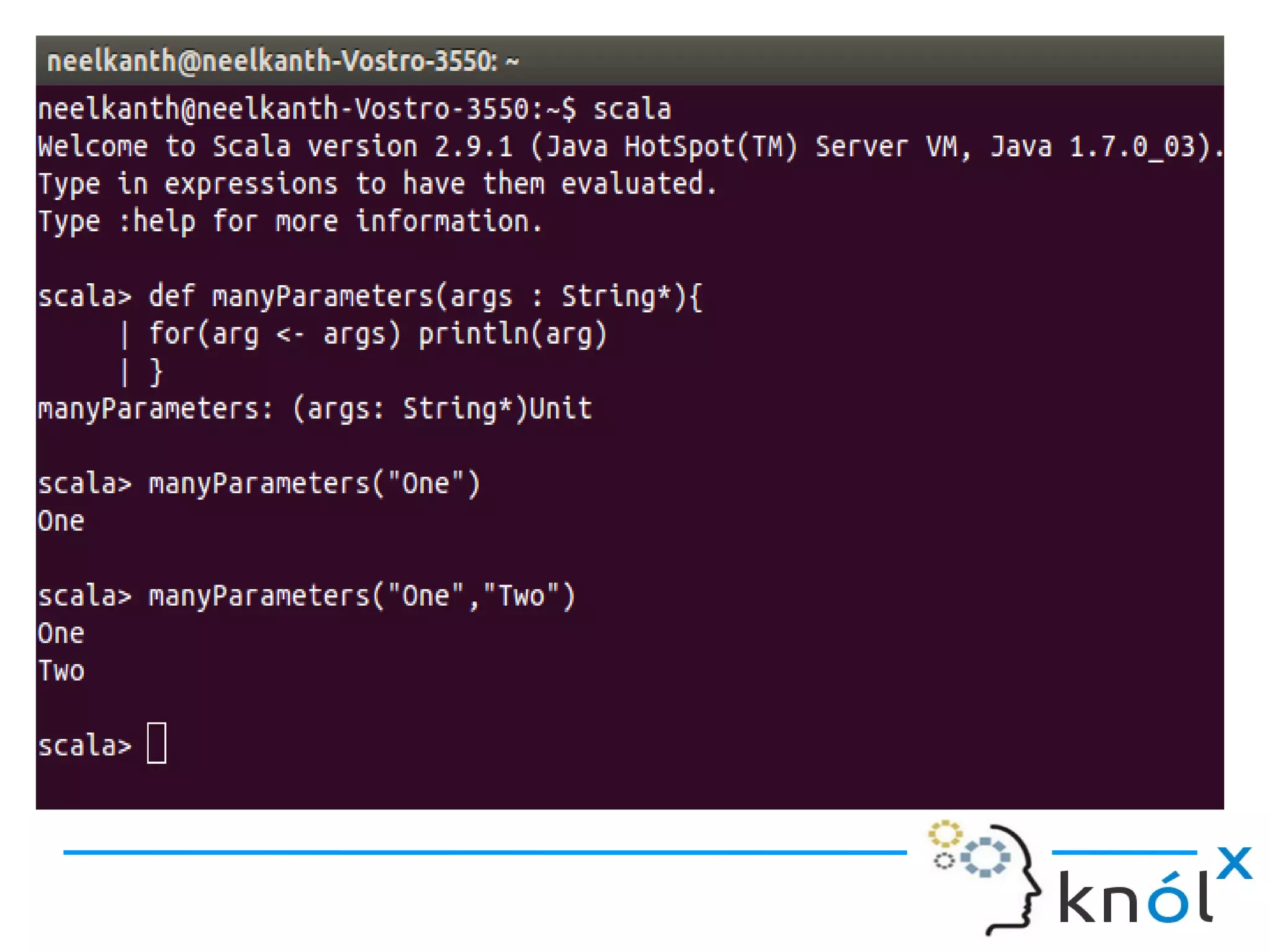

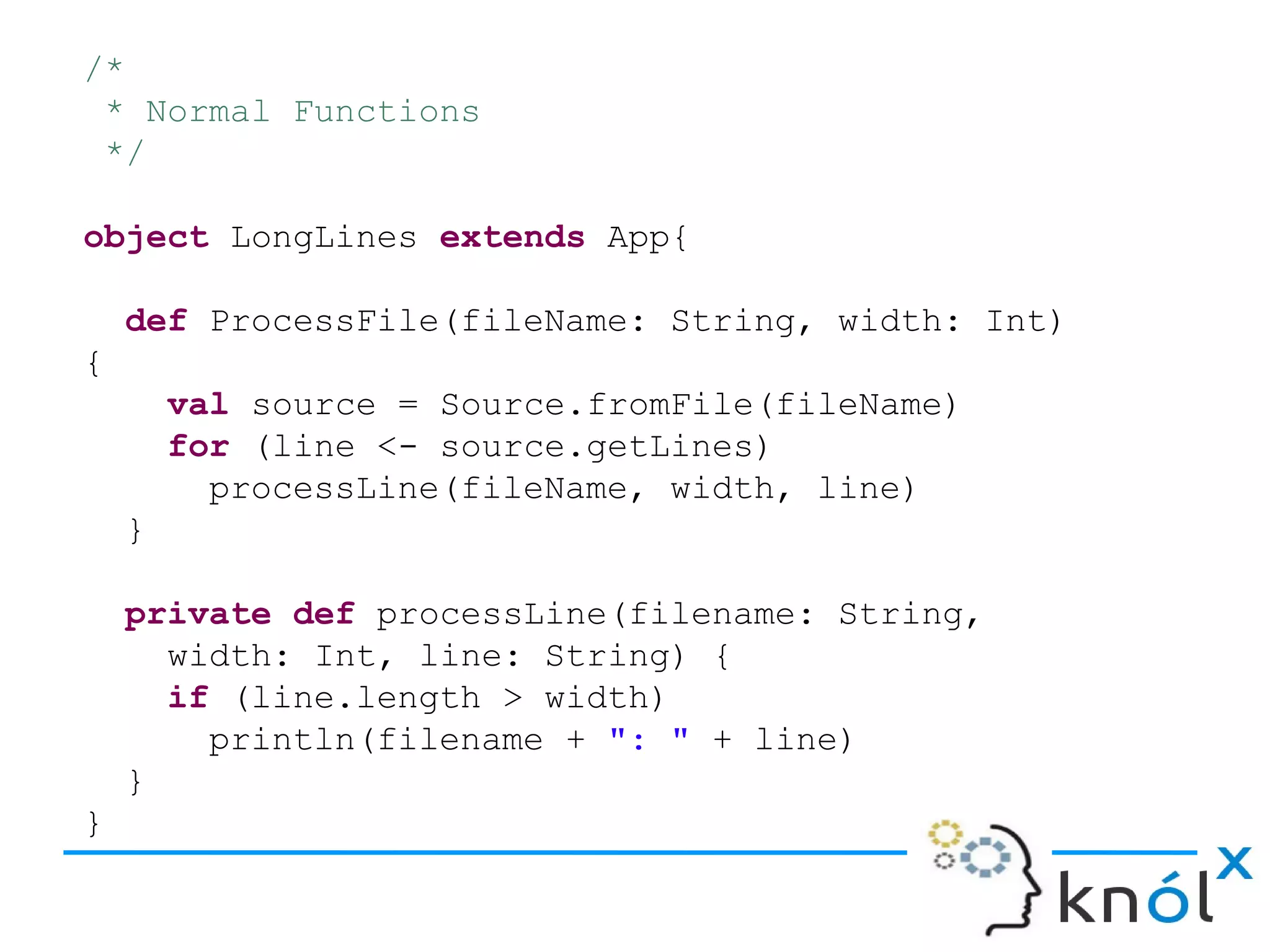

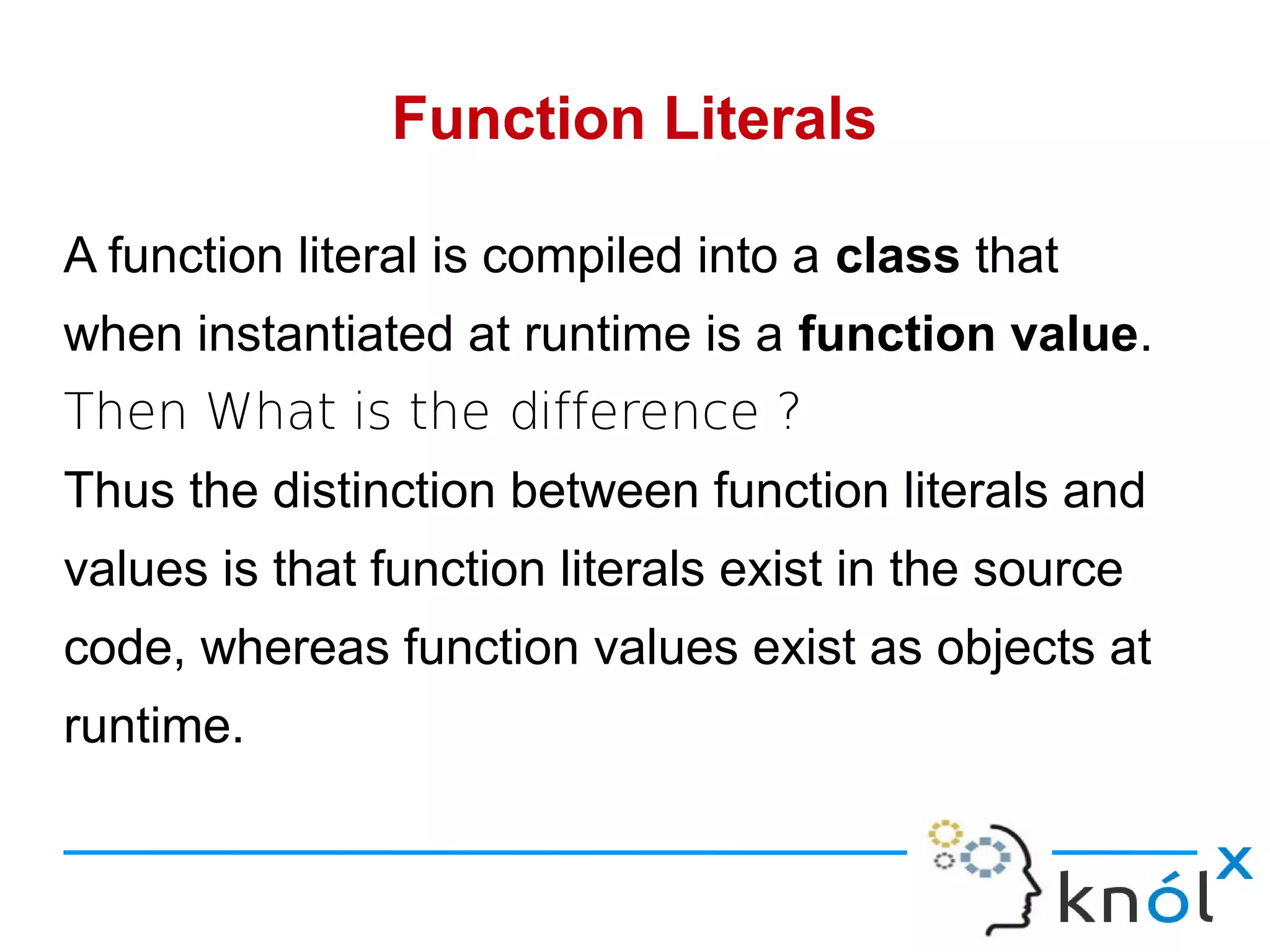

Scala supports first-class functions that can be passed as arguments to other functions or stored in variables. Functions can be defined as method members or as anonymous function literals. Function literals allow defining unnamed functions inline. Functions in Scala support closures, where functions can close over variables in the enclosing scope. This allows functions to access variables that are not passed in as arguments. The document discusses various ways to define functions in Scala including local functions, function literals, partially applied functions, and repeated parameters.

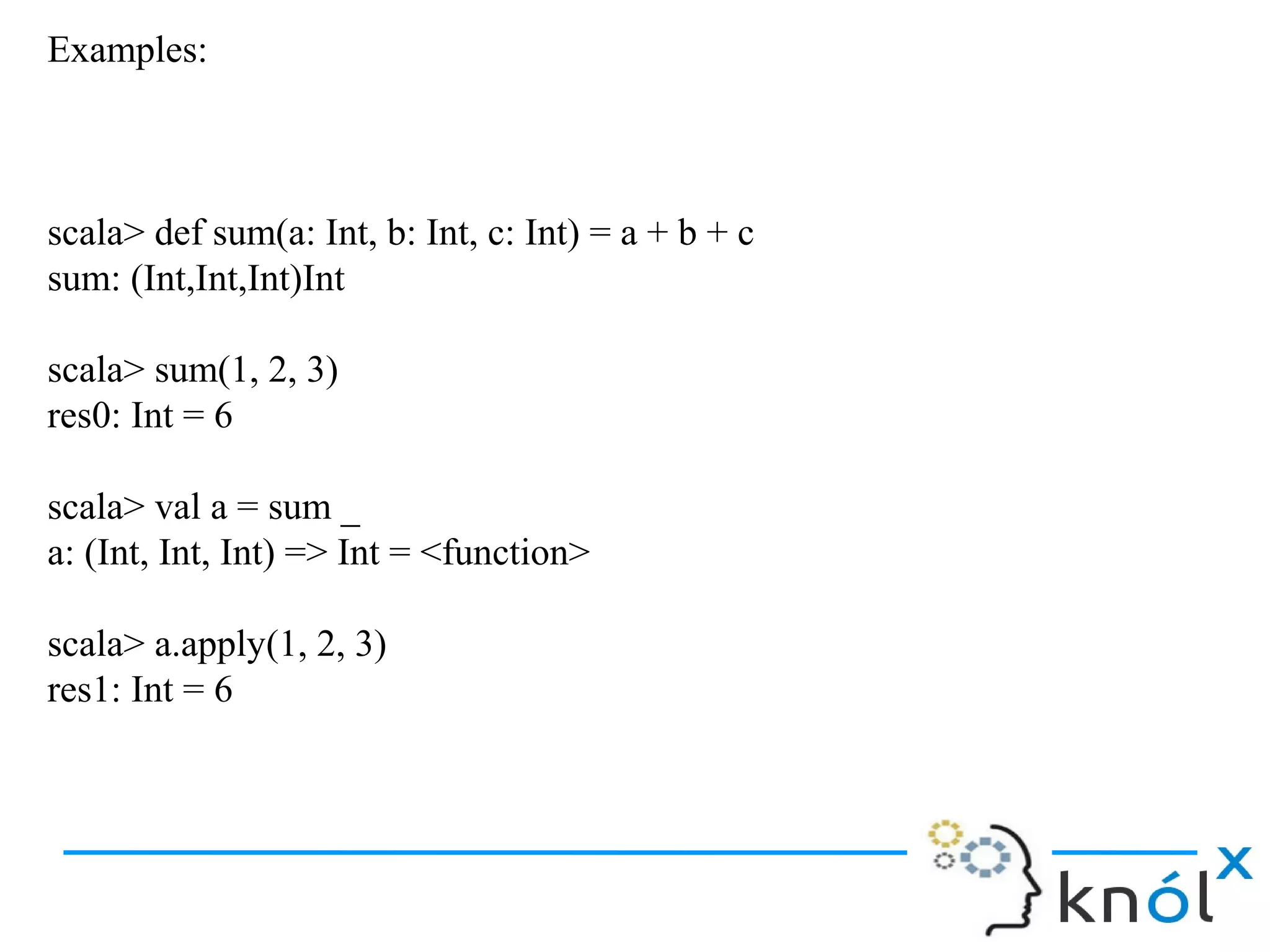

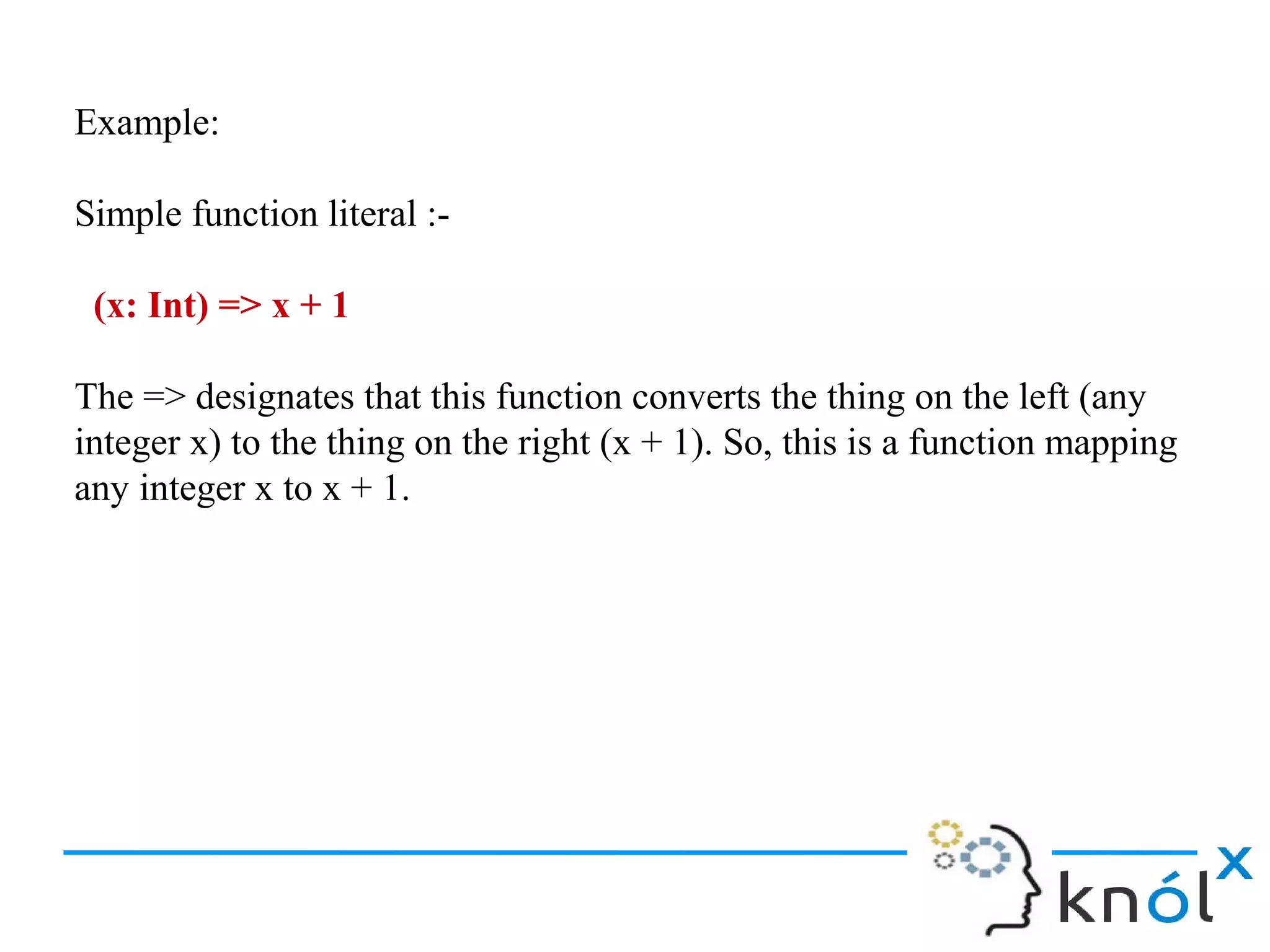

![We've seen the nuts and bolts of function literals and function

values. Many Scala libraries give you opportunities to use

them e.g

foreach method:

scala> val someNumbers = List(-11, -10, -5, 0, 5, 10)

someNumbers: List[Int] = List(-11, -10, -5, 0, 5, 10)

scala> someNumbers.foreach((x: Int) => println(x))

filter method:

scala> someNumbers.filter((x: Int) => x > 0)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/functionsclosures-120808053933-phpapp01/75/Functions-closures-11-2048.jpg)

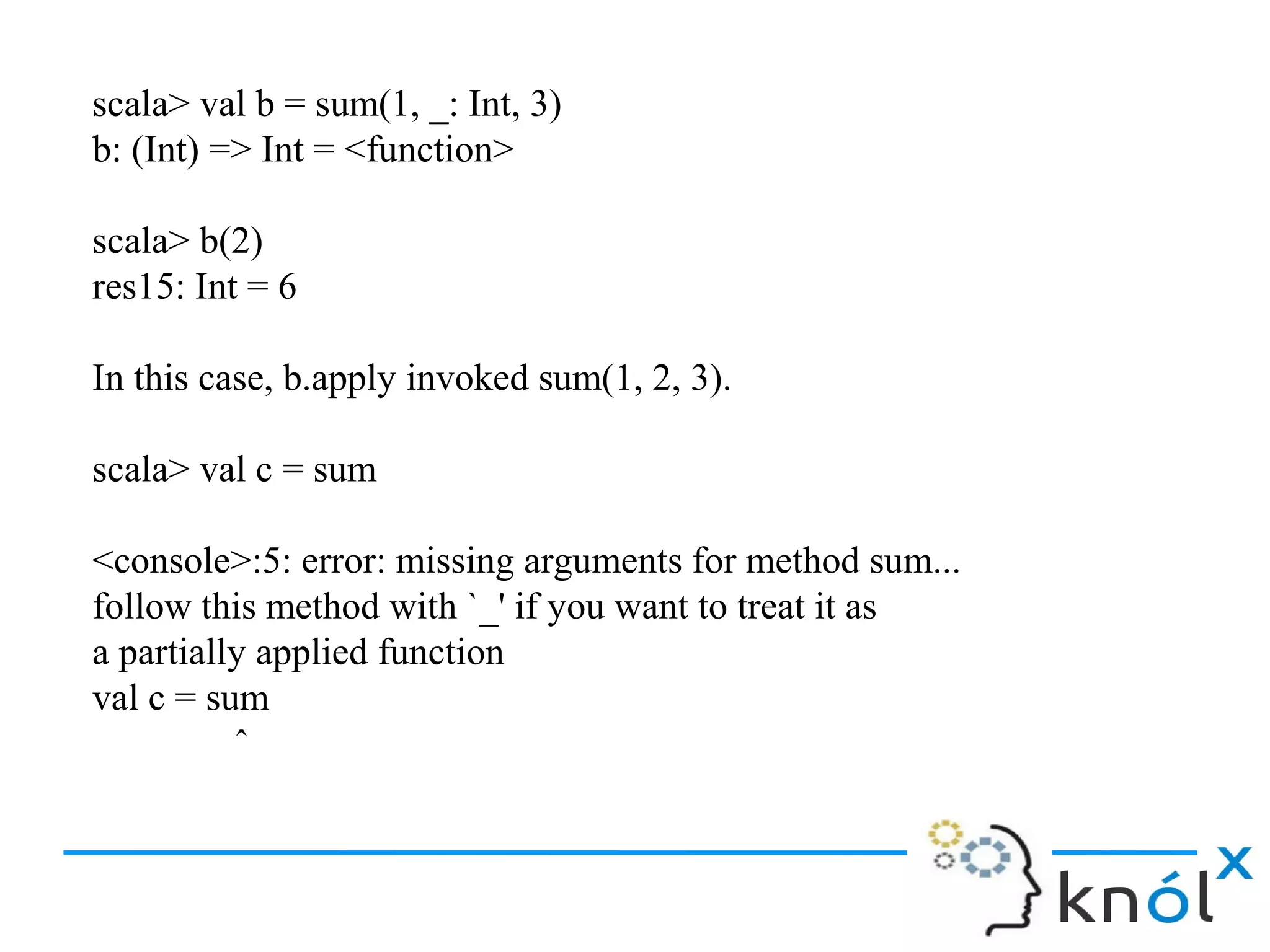

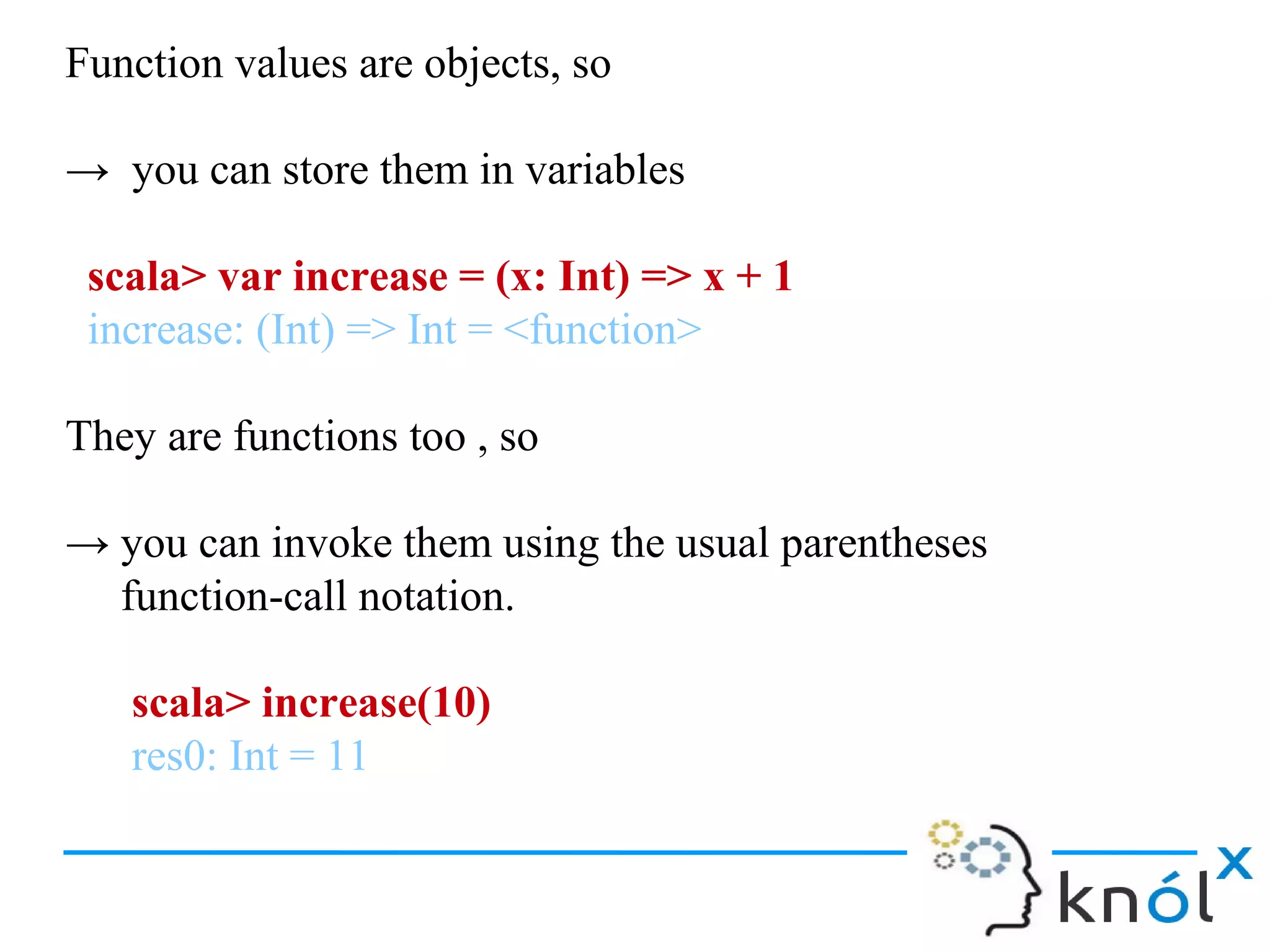

![Short forms of function literals

Scala provides a number of ways to leave out redundant information and

write function literals more briefly. Keep your eyes open for these

opportunities, because they allow you to remove clutter from your code.

One way to make a function literal more brief is to leave off the parameter

types. Thus, the previous example with filter could be written like this:

scala> someNumbers.filter((x) => x > 0)

res7: List[Int] = List(5, 10)

Even leave the parentheses around x

scala> someNumbers.filter( x => x > 0)

res7: List[Int] = List(5, 10)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/functionsclosures-120808053933-phpapp01/75/Functions-closures-12-2048.jpg)

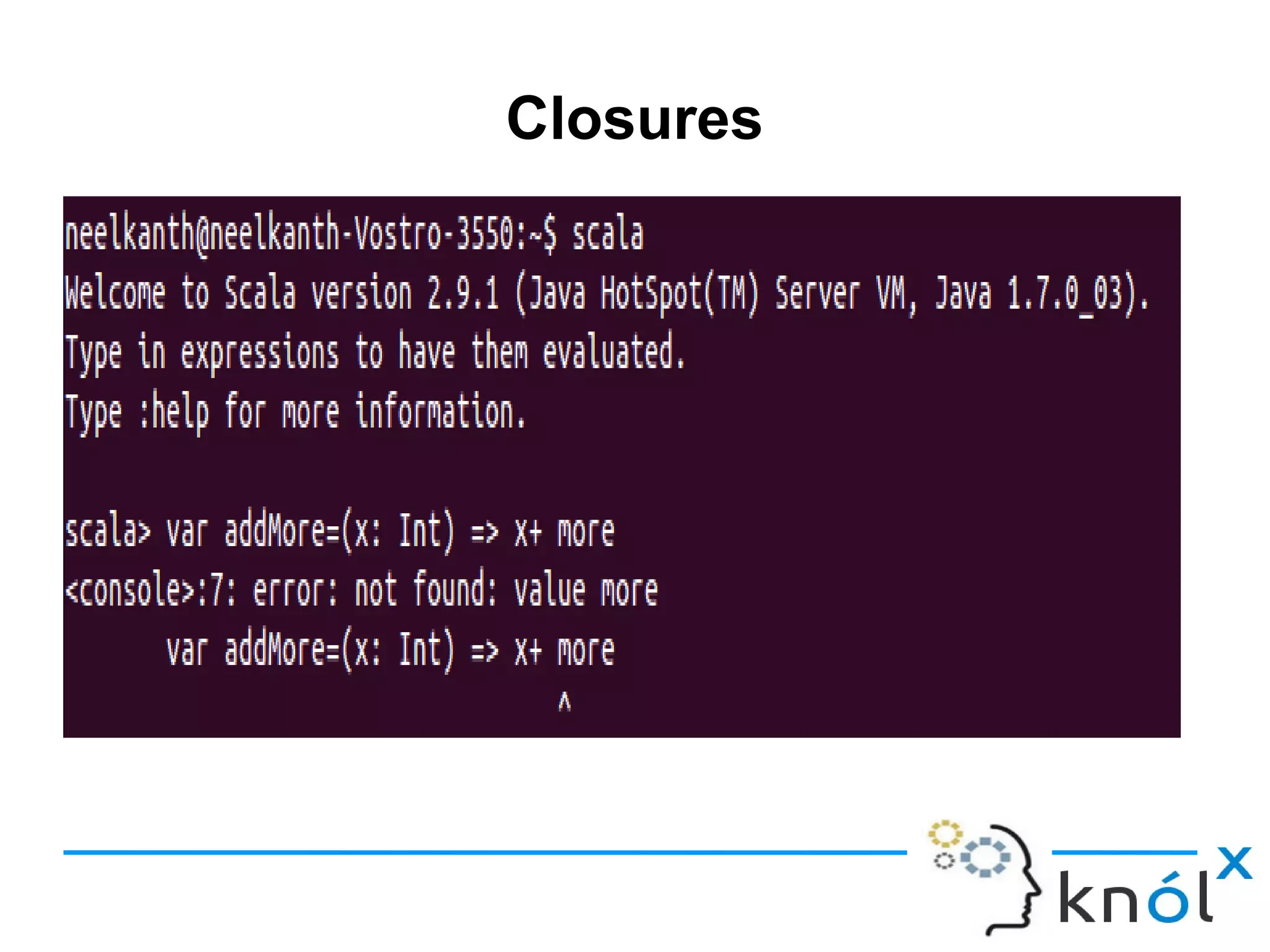

![Placeholder syntax

To make a function literal even more concise, you

can use underscores as placeholders for one or

more parameters, so long as each parameter

appears only one time within the function literal.

scala> someNumbers.filter( _ > 0)

res9: List[Int] = List(5, 10)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/functionsclosures-120808053933-phpapp01/75/Functions-closures-13-2048.jpg)