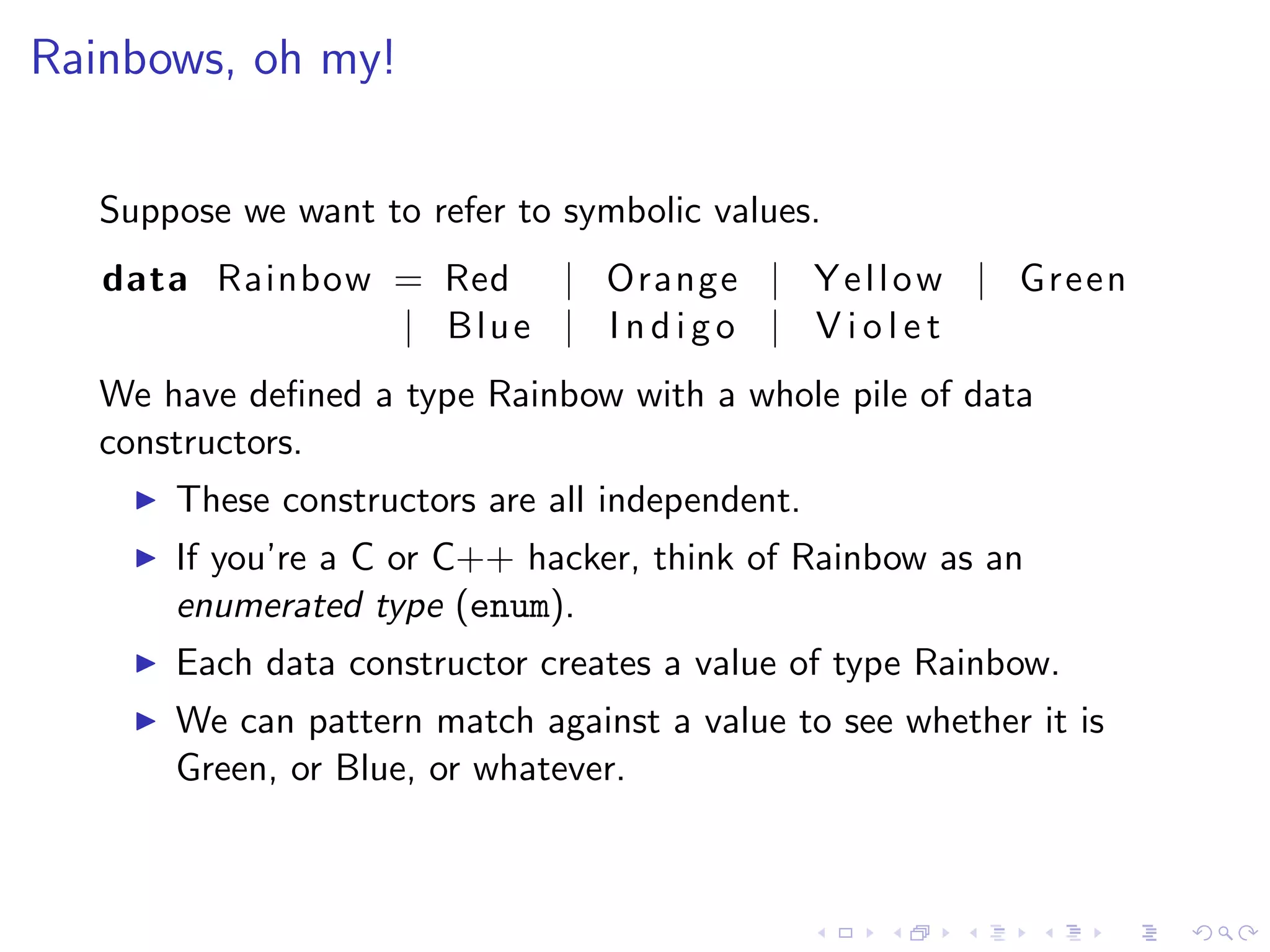

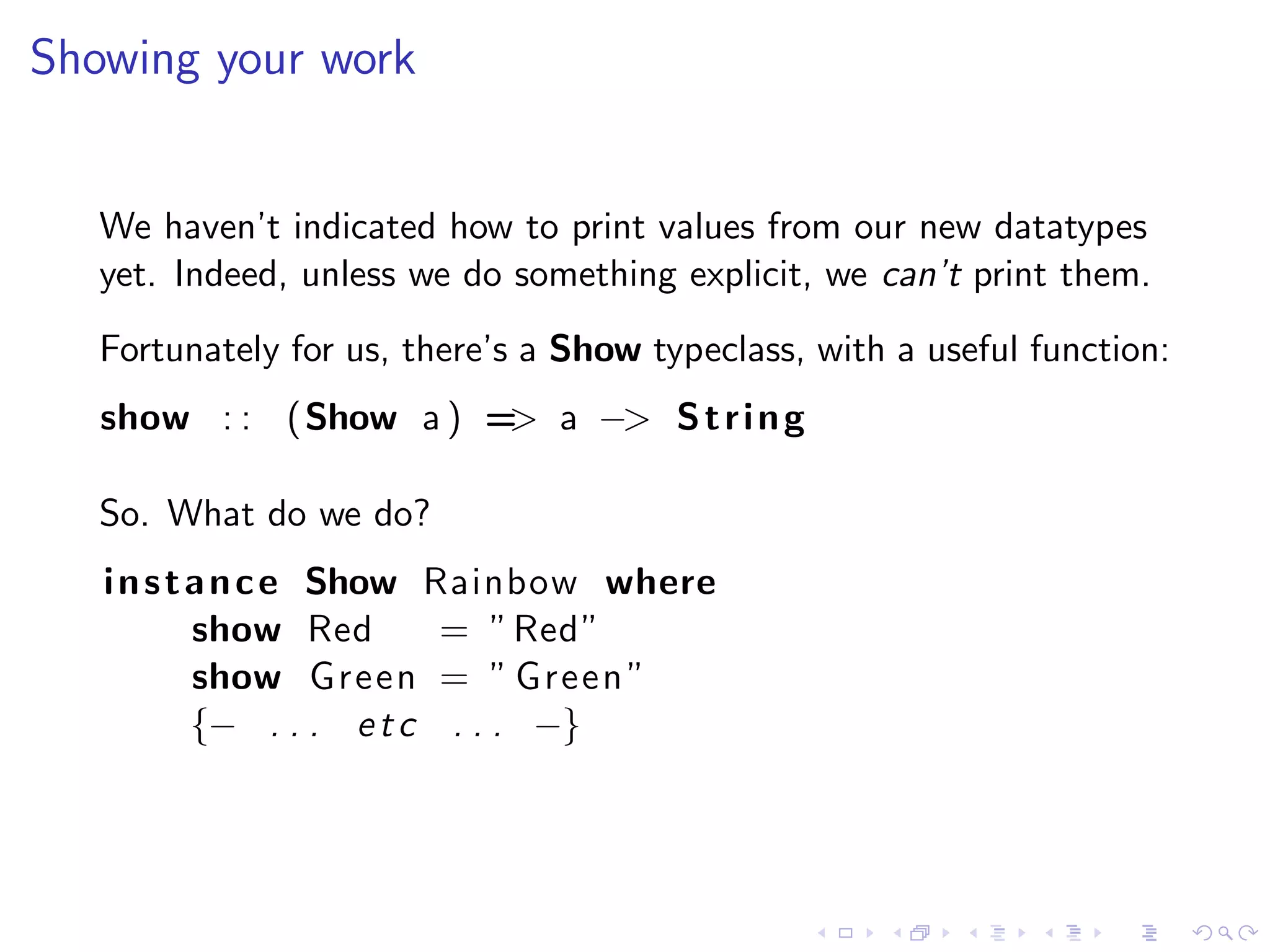

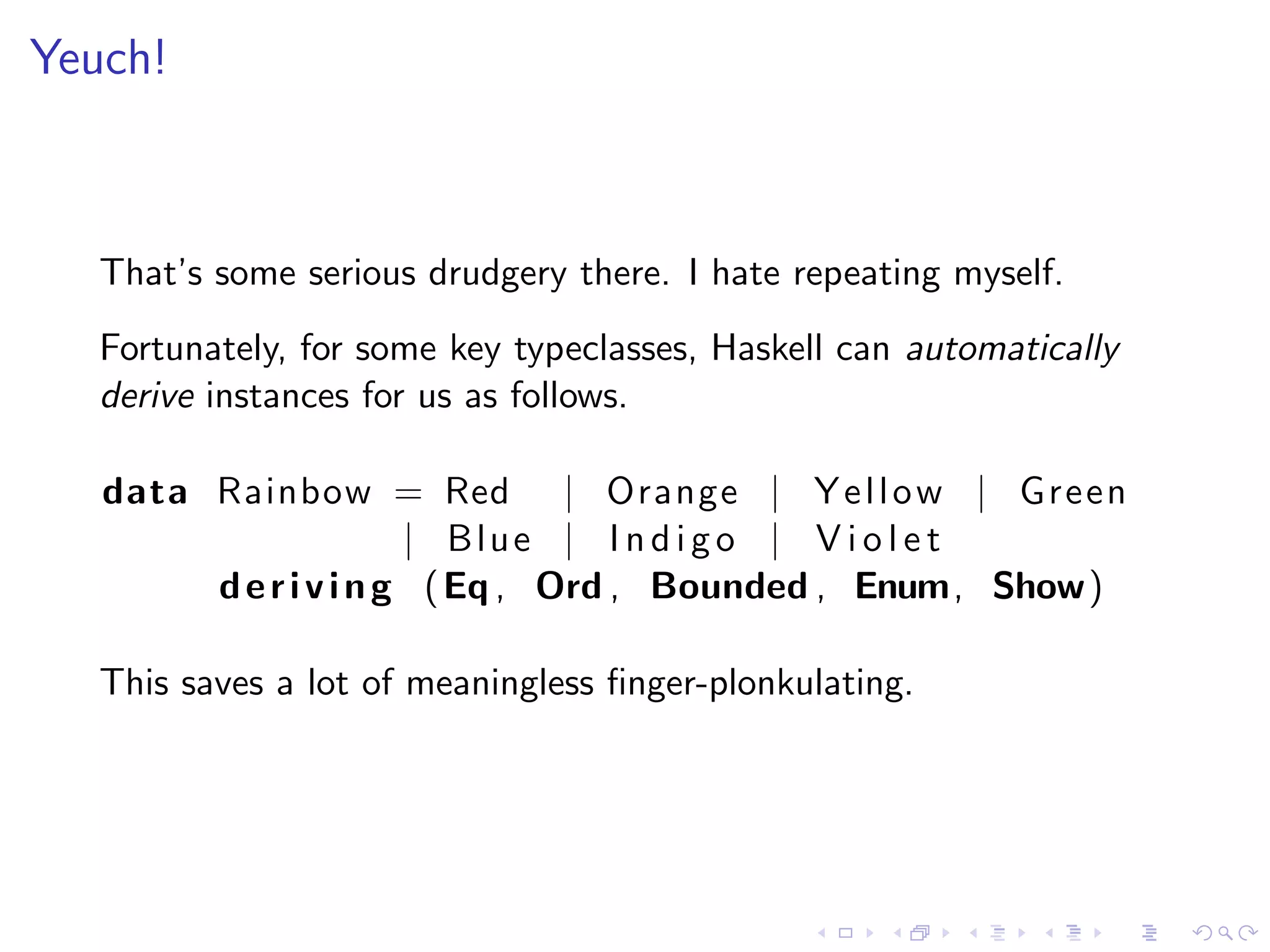

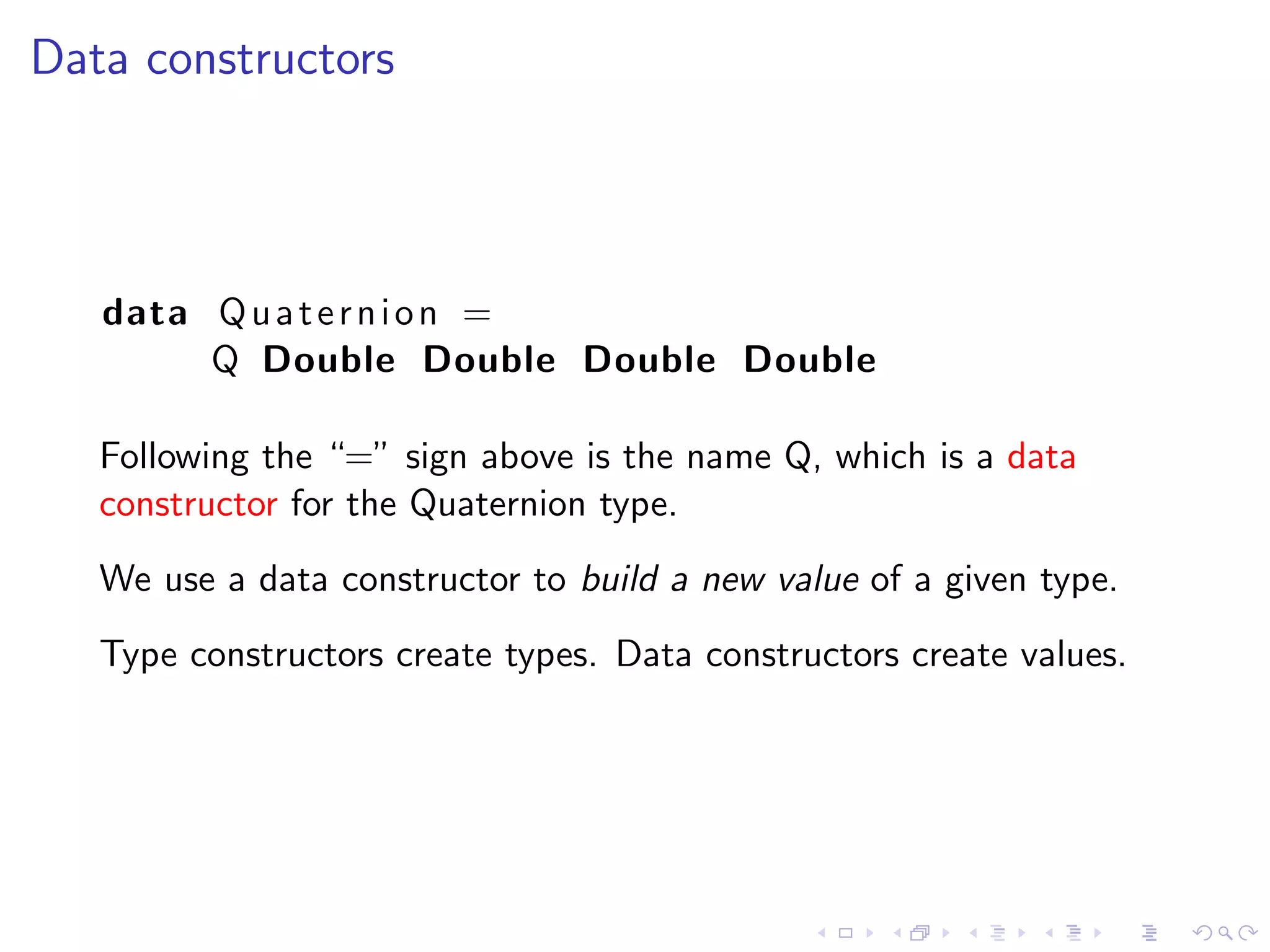

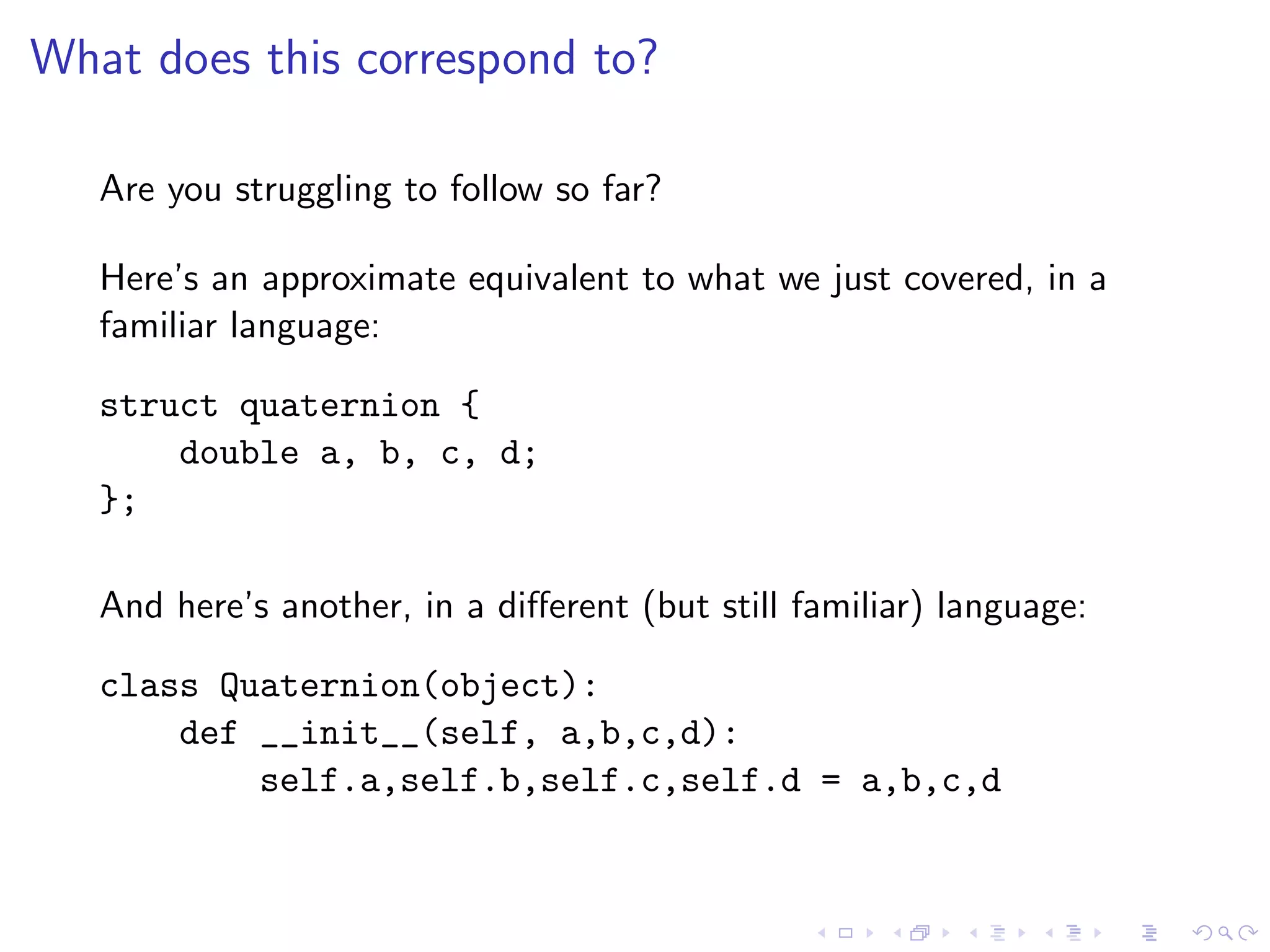

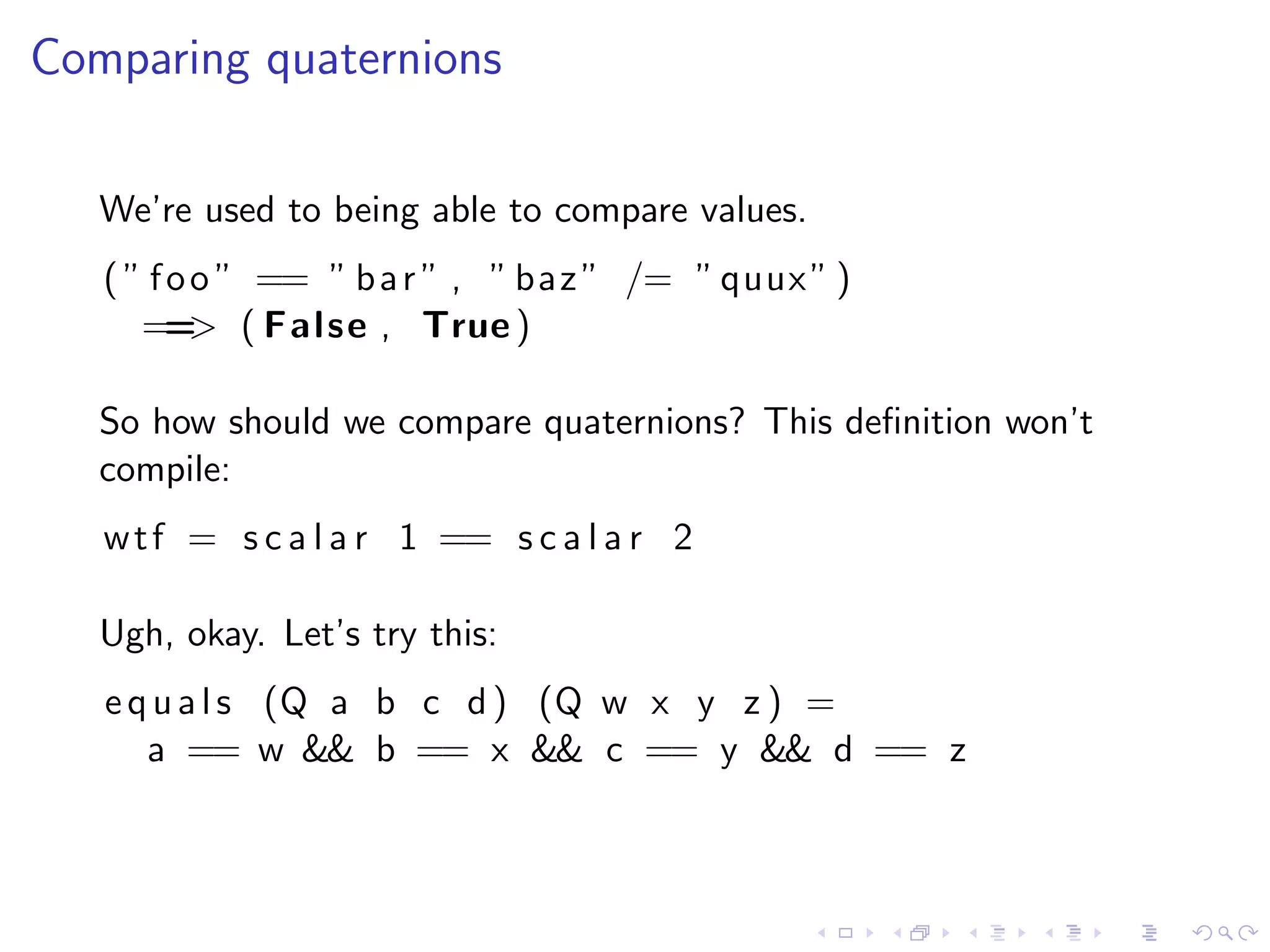

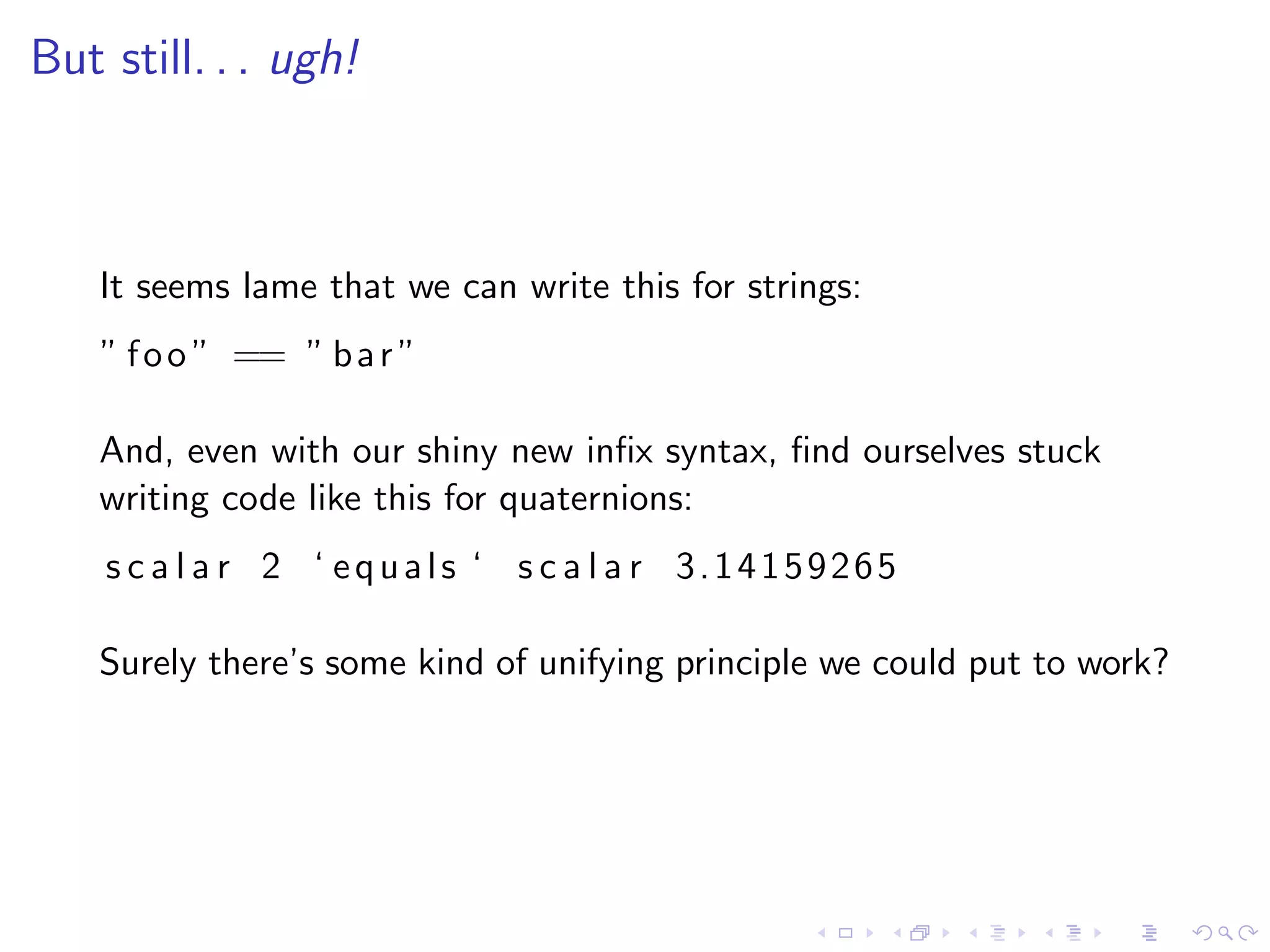

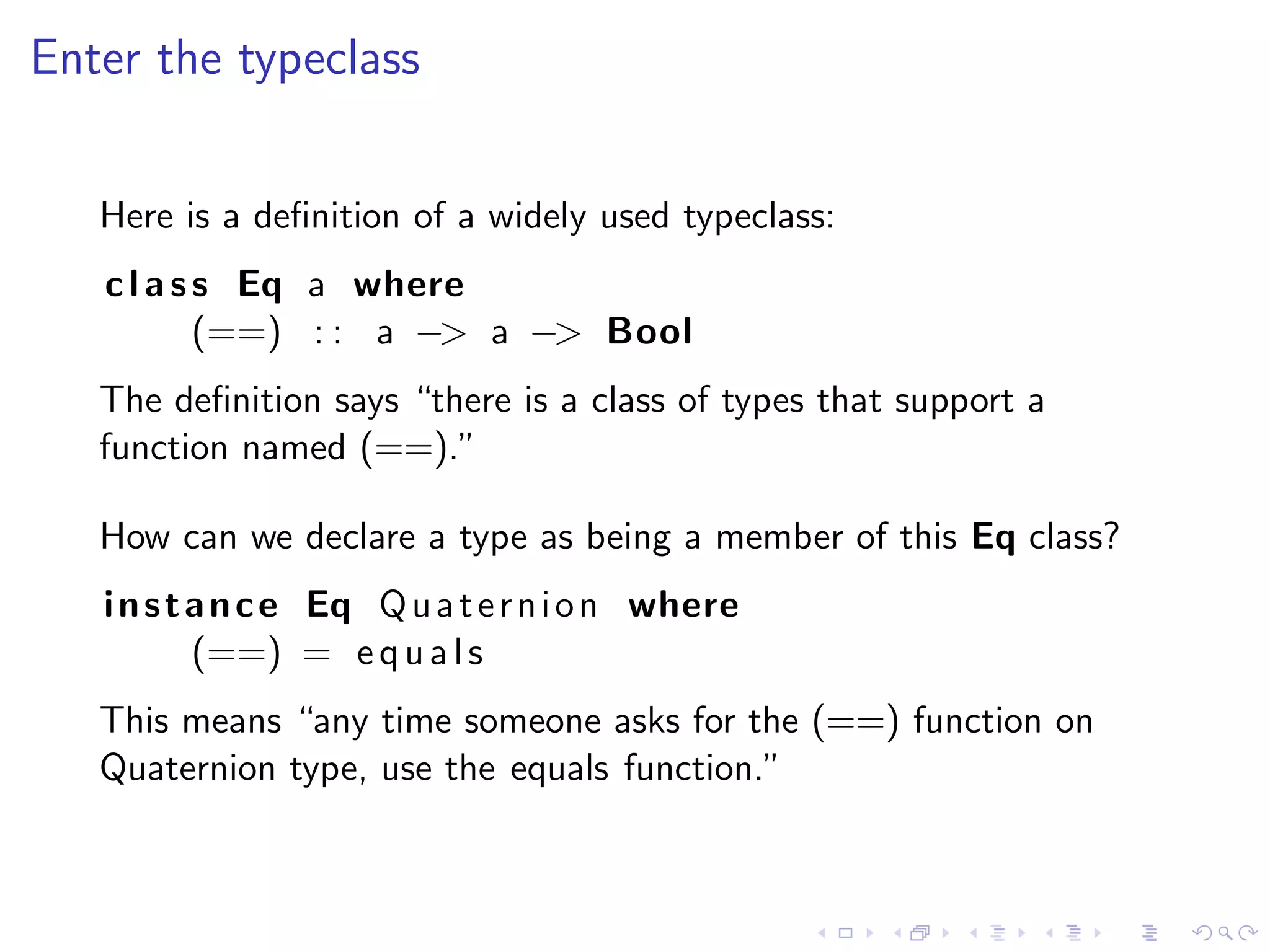

This document summarizes a lecture about quaternions and how to represent them in Haskell using algebraic data types and type classes. It introduces quaternions, defines a Quaternion data type, and shows how to use data constructors to create and pattern match quaternion values. It also discusses type classes like Eq and Show that allow quaternions to be compared and printed by making Quaternion an instance of these classes. Finally, it provides homework problems about working with points and angles in 2D space.

![Using constructors (II)

Remember the data constructors for lists?

(:) : : a −> [ a ] −> [ a ]

[] :: [a]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture4-091029120506-phpapp01/75/Real-World-Haskell-Lecture-4-8-2048.jpg)

![Using constructors (II)

Remember the data constructors for lists?

(:) : : a −> [ a ] −> [ a ]

[] :: [a]

We use data constructors to create new values.

foo = ’ f ’ : ’o ’ : ’o ’ : [ ]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture4-091029120506-phpapp01/75/Real-World-Haskell-Lecture-4-9-2048.jpg)

![Using constructors (II)

Remember the data constructors for lists?

(:) : : a −> [ a ] −> [ a ]

[] :: [a]

We use data constructors to create new values.

foo = ’ f ’ : ’o ’ : ’o ’ : [ ]

We use type constructors in type signatures.

stripLeft : : [ Char ] −> [ Char ]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture4-091029120506-phpapp01/75/Real-World-Haskell-Lecture-4-10-2048.jpg)

![Using constructors (II)

Remember the data constructors for lists?

(:) : : a −> [ a ] −> [ a ]

[] :: [a]

We use data constructors to create new values.

foo = ’ f ’ : ’o ’ : ’o ’ : [ ]

We use type constructors in type signatures.

stripLeft : : [ Char ] −> [ Char ]

We pattern match against data constructors to inspect a value.

s t r i p L e f t ( x : xs ) | isSpace x = s t r i p L e f t xs

| otherwise = x : xs

stripLeft [] = []](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture4-091029120506-phpapp01/75/Real-World-Haskell-Lecture-4-11-2048.jpg)

![Notational aside: functions and operators

Functions and operators are the same, save for fixity. We usually

apply functions in prefix position, and operators in infix position.

However, we can treat an operator as a function by wrapping it in

parentheses:

(+) 1 2

(:) ’a ’ [ ]

zipWith (+) [ 1 , 2 , 3 ] [ 4 , 5 , 6 ]

We can also apply a function as if it was an operator, by wrapping

it in backquotes:

s c a l a r 1 ‘ equals ‘ scalar 2

” wtf ” ‘ isPrefixOf ‘ ” wtfbbq ”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture4-091029120506-phpapp01/75/Real-World-Haskell-Lecture-4-21-2048.jpg)

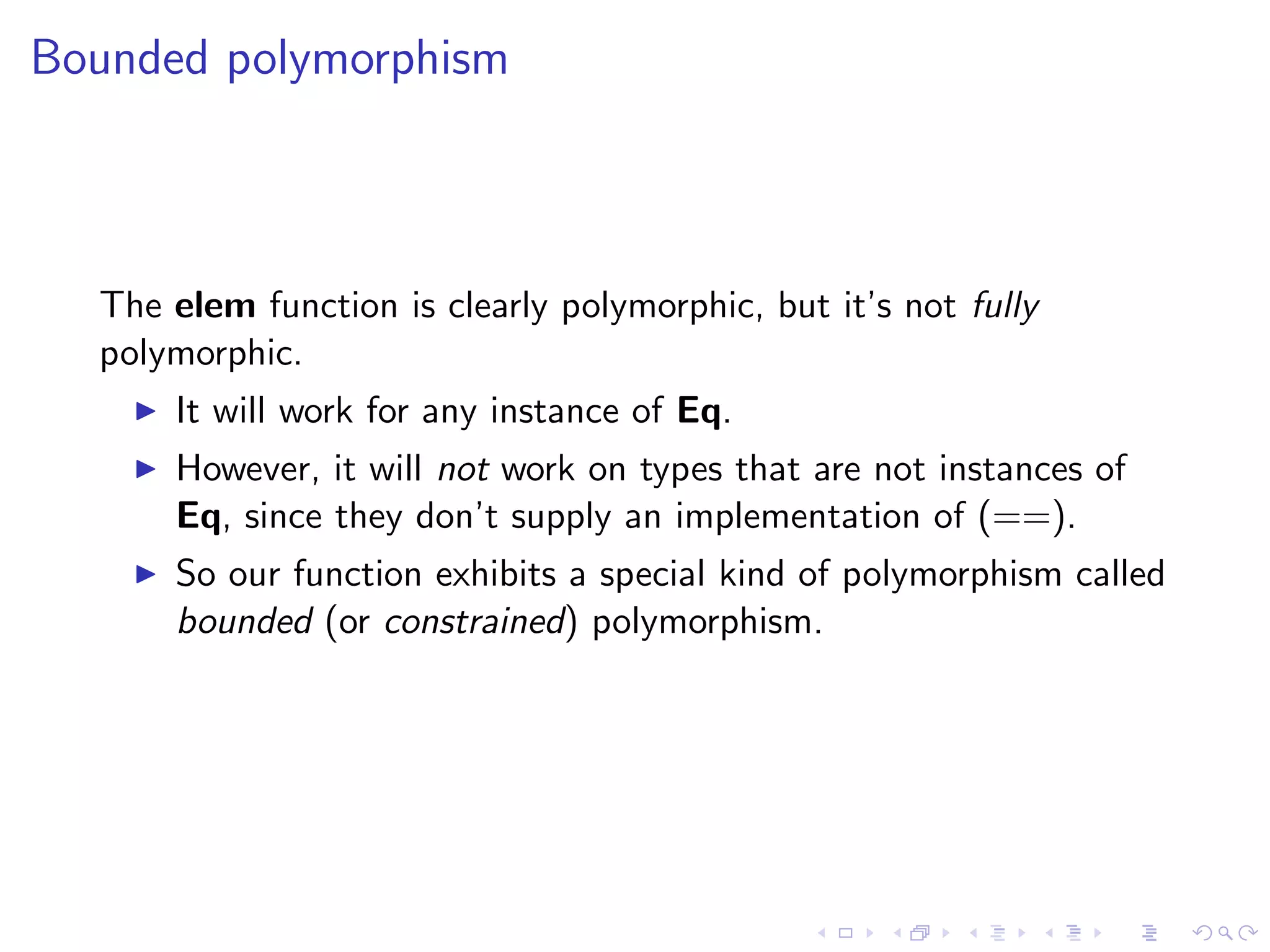

![Use of (==)

As we know, we can use the (==) operator when writing functions:

elem a [ ] = False

elem a ( x : x s )

| a == x = True

| o t h e r w i s e = elem a x s

Notice something very important:

This function needs to know almost nothing about the type of

the values a and x.

It’s enough to know that the type supports the (==)

function, i.e. that it’s an instance of the Eq typeclass.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture4-091029120506-phpapp01/75/Real-World-Haskell-Lecture-4-25-2048.jpg)

![Expressing bounded polymorphism

We can express the fact that elem only accepts instances of Eq in

its type signature:

elem : : ( Eq a ) = a −> [ a ] −> Bool

>

The “(Eq a) =>” part of the signature is called a constraint.

In the absence of a type signature, a Haskell compiler will infer the

presence of any necessary constraints.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture4-091029120506-phpapp01/75/Real-World-Haskell-Lecture-4-27-2048.jpg)

![Expressing bounded polymorphism

We can express the fact that elem only accepts instances of Eq in

its type signature:

elem : : ( Eq a ) = a −> [ a ] −> Bool

>

The “(Eq a) =>” part of the signature is called a constraint.

In the absence of a type signature, a Haskell compiler will infer the

presence of any necessary constraints.

Aside: Haskell’s kind of polymorphism is called parametric. In this

type signature:

(++) : : [ a ] −> [ a ] −> [ a ]

The type of (++) is parameterized by the type variable a.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture4-091029120506-phpapp01/75/Real-World-Haskell-Lecture-4-28-2048.jpg)